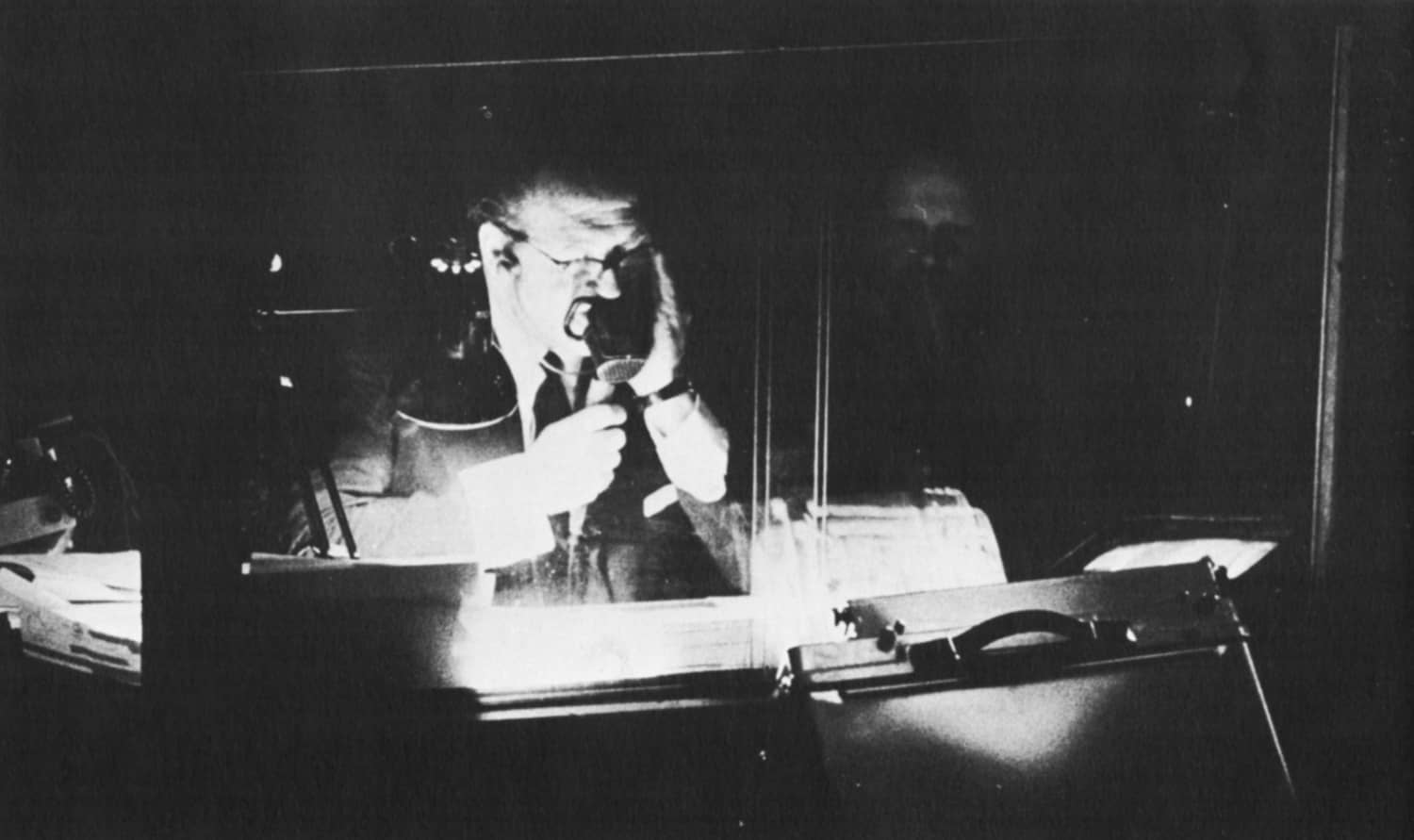

Dimbleby pressed on into Germany. He entered Berlin with the first Allied troops and was the first war correspondent into the prostrate capital. He broadcast from Hitler’s chair in his bombed study, and acquired as souvenirs knives, forks and spoons with the initials A.H., which he later provided at dinner parties for people he didn’t like. He was also locked up by a Red Army patrol, and released after he had persuaded them that he was the son of Winston Churchill.

As we would say, in British Air Force slang, ‘Berlin has had it’. As a clean, solid, efficient city, it has ceased to exist. In its place is a broken-down, evil-smelling rabbit warren of craters, and hulks of buildings, and everywhere dust and dirt and squalor. It’s true you can go into one or two streets and see no more damage, as you look along the sidewalk, than you might see in London. But turn the corner, and again and again you come face to face with a chaos and a confusion that reminds you of those picture postcards showing ruined towns of the last war, the result of 65,000 tons of bombs, and the savage street fighting of two months ago. The spirit of the people has been shattered too. I’ve talked to a good many Germans in the last three or four months. And these Berliners are the first completely cowed and submissive people I’ve met. They’ve no spirit at all, only an instinctive urge to live, and that’s not very easy for the Berliner today.

I’m not asking your sympathy for them, but there are certain hard-and-fast conclusions we can and must draw. Allied Military Government has got here one of the most difficult jobs it’s had to tackle; all its earlier struggles in the Ruhr and the west of Germany fade into nothing when compared with this paralysed capital to be administered by three foreign powers, one of which, the Russian, has ideas and methods that differ from ours.

First, there is the problem of supply. Great quantities of food and drugs are needed now before the winter, not necessarily because we have pity for these people who are slowly starving, but because if we let them get any weaker, there will be epidemics of disease later in the year, and we cannot allow epidemics where we have allied troops stationed. There are already enough dead bodies. They are estimated in thousands. Still buried in the great heaps of rubble in this city and never to be rescued, enough for us to avoid any more deaths if possible.

Already the stench in parts of the centre of Berlin is nauseating and the city’s water system is polluted. The incidence of venereal disease among the population is serious, and the German hospitals haven’t enough drugs to give proper treatment. There’s not yet been a major epidemic of typhus or cholera, but most of the population is in such a weak state that if an epidemic did start it would spread like wildfire.

For three months now there’s been no refuse collection of any kind. When the Russians entered the city in April, they made each housewife responsible for the street in front of her house and this had to be clear and clean by 7 o’clock in the morning. That rule still obtains, at least it’s still obeyed. When it came into force many of the streets of the Zehlendorf suburb in which I’m living were blocked with the debris of air-raids.

The woman who keeps our house – she was English until she married a German naval officer forty years ago – herself shifted nearly ten tons of rubble in ten days’ solid work in two coal buckets. There’s hardly any household refuse. She has very little to eat and wastes nothing, but what there is she carries to a communal dump a mile away.

There can be no doubt that the Germans, and particularly the German women, can be made to do everything for themselves. That is a reasonable burden for them to bear, but certain tools and material must be provided soon or they’ll be too weak to work at all. Already they’ve abandoned the once regular practice of going out to the market a few miles south of us here for a few pounds of fresh fruit; the exhaustion of the journey and the wear on their shoe leather – people’s toes are visible everywhere, and it’s been pouring with rain for ten days – these things make the trip no longer worth while.

One other major problem still confronts us, and it’s something that isn’t easy to bring up, though no one here will be an honest correspondent if he ignores it, and that is the question of our relations with the Russians. They have fought a remarkable series of battles, ending with the savage struggle in the city which brought them their final victory. I don’t doubt that to do that the Red Army needed the tightest discipline and the most rigid security; but now that the fighting is over, the security, if not the discipline, can be relaxed, at least enough to enable the Western allies to get on friendly terms with their Russian partner.

We must get on good terms. Without co-operation and some degree of trust we can hope nothing for the future. At the moment that trust is lacking. Somewhere between us and the Russians there’s a barrier of suspicion and reserve. It’s rather like trying to make friends with a fellow that you can’t see on the other side of a high wall. Language, of course, is a major difficulty, generally speaking we can’t understand a word they say, and they don’t understand us, and there’s strictly a limit to what you can accomplish with smiles and handshakes and nods.

After a week in Berlin and a good deal of superficial contact with the Red Army, it appears unhappily that the Red Army’s officers and men are working to strict rules that have been laid down, and that one of those rules is that they must avoid too much contact with the Americans and the British. Perhaps we can hope that that rule is going to be altered. In a sense, of course, this racial reticence is understandable. We haven’t been on particularly good terms with the Soviet Union for the past twenty-five years, and there’s no reason why the Red Army should suddenly regard us as its bosom friend, just because we teamed up against Germany, but I do wish that we could make the Russians believe that in a place like this, where we’re all shoulder to shoulder for the first time, we mean well and not ill, and can be trusted.

At present, passing through the Brandenburg Gate, which marks the boundary between the British and the Soviet zones of occupation in Berlin, is like crossing a frontier. There are no barriers at all, but you can sense a different atmosphere on the eastern side. You get the feeling that while you’re tolerated you’re not welcome, and you’re not at all certain what’s going to happen.

Let me give you an example of what does happen. Four days ago I went to Hitler’s Chancellery to have a look round the Fuhrer’s study and his private room. Now the Chancellery is in the Wilhelmstrasse, and the whole of this Nazi government area is under Russian control with a special commandant in command. I had lunch with him in his headquarters underground – a cheerful, friendly meal. We discussed the Red Army, the Russian policy freely and at length, and we criticised and received criticism in return.

Two days ago, on my way to a British military conference at the Victory column in Berlin central park, the Tiergarten, I made a through detour to see something of the Leipzigstrasse, Leipzig Street, one of the streets along which I’ve not driven. It’s true that I was about two hundred yards deeper in the Soviet zone than I had been for lunch two days before. Half way down the Leipzigstrasse, I was stopped by a Red Army patrol with tommy-guns. I was forced to leave my car and go into a house, where I was locked in a room. It took me twenty minutes of strong language and fist shaking to get out, to get hold of an officer and to get freed, with the apology that it had been a mistake.

Now this was only an incident; in itself it was quite unimportant, but these mistakes are happening all over the place all the time, a continual succession of pin-pricks upsetting our relations and preventing us from getting them established on a strong and permanent footing. They affect everything, from the original movement of our occupying forces in Berlin, which was not accomplished without some difficulty and a great deal of delay, to the present movement of our supply convoys, and the conditions in which our special troops here in connection with the forthcoming big conference [Potsdam] are having to live.

But to return to the people of Berlin. There are two sorts of them; one whose orderly and ordered life has come to pieces, and the other who can get along whatever the conditions. I’ve seen them both in the past few days. The first was a detective inspector of the Police Department to whom I’d gone to check an address, knowing that the Berlin police had a secret dossier on everyone in the city. I found him aged and distraught. He waved to a heap of paper and cardboard blackened and dripping in his outer office. ‘All my files,’ he said, ‘all my files burned black, no check on anyone now, no check.’ And to him, the fact that the citizens of Berlin were no longer under the iron rule of the police was the ultimate disaster.

And the second Berliner, the other kind I met on the front doorstep of Hitler’s Chancellery where a crowd of people were watching the coming and going. He came to me from a group of civilians. He was a Jew, with a briefcase in one hand, and he said: ‘Excuse me, but would you like a tour of Berlin? To see the ruins, the Reich Chancellery, Goebbels’s Palace, Gestapo Headquarters?’ He rattled them off, and the price at the end, and as I looked at him I thought how for ten years in this city the Nazis had been insulting him and beating him, and how for ten long years they’d deported him and tortured him and starved him and gassed him, and here he was on Hitler’s doorstep in 1945 when all his persecutors were dead or captured, and I wondered how on earth he’d stayed alive.

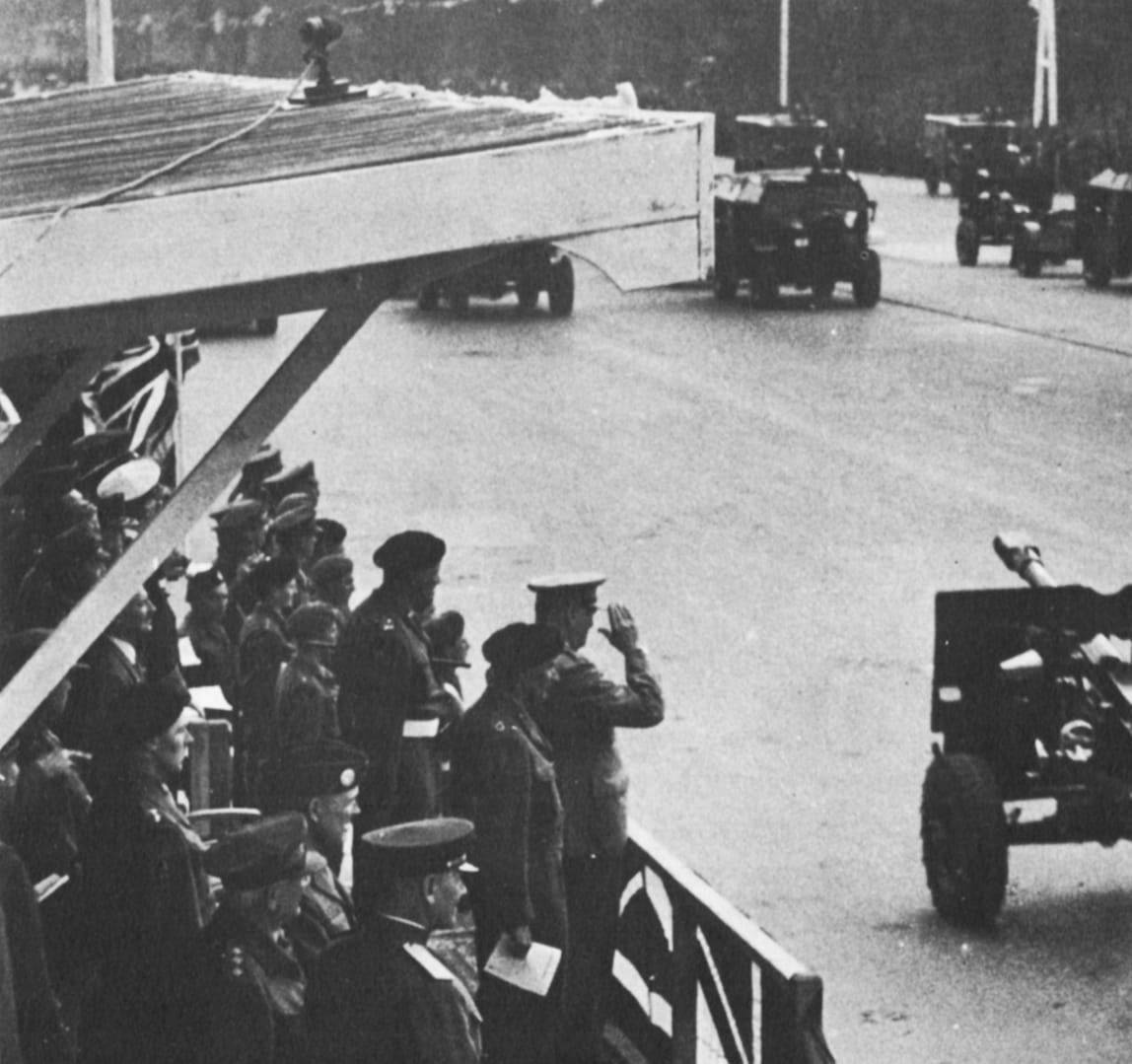

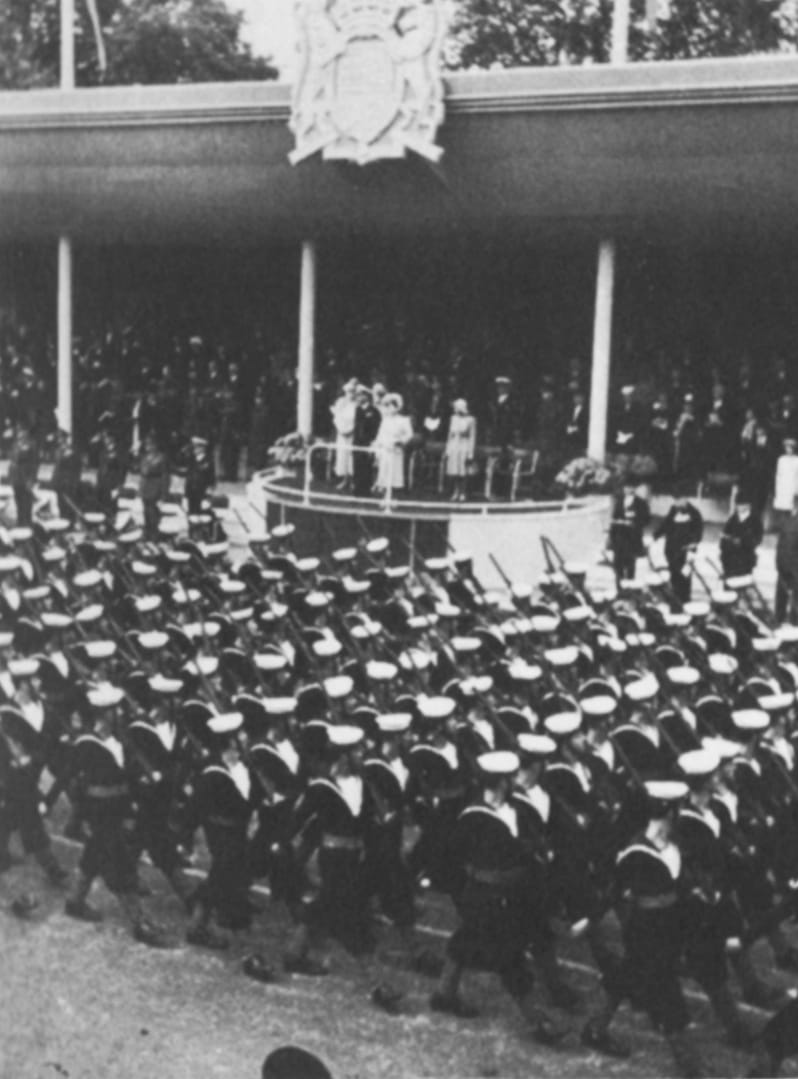

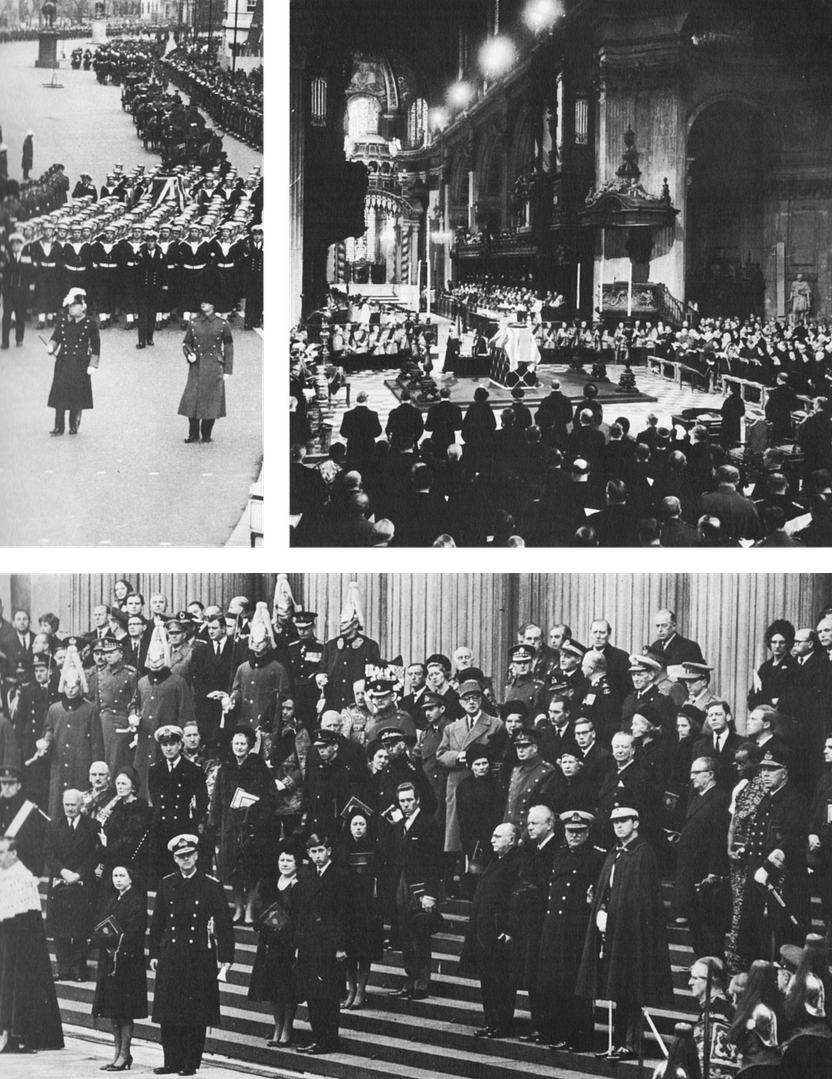

Some newspapers were sharply critical of what Dimbleby said about the Russians, but Richard quietly rode the storm. He was the commentator when Churchill, with Montgomery at his side, took the Victory Parade in Berlin. In five weeks he sent 144 despatches from Berlin, only nine of which were crowded out or rejected. It was a brilliant end to his war reporting career.

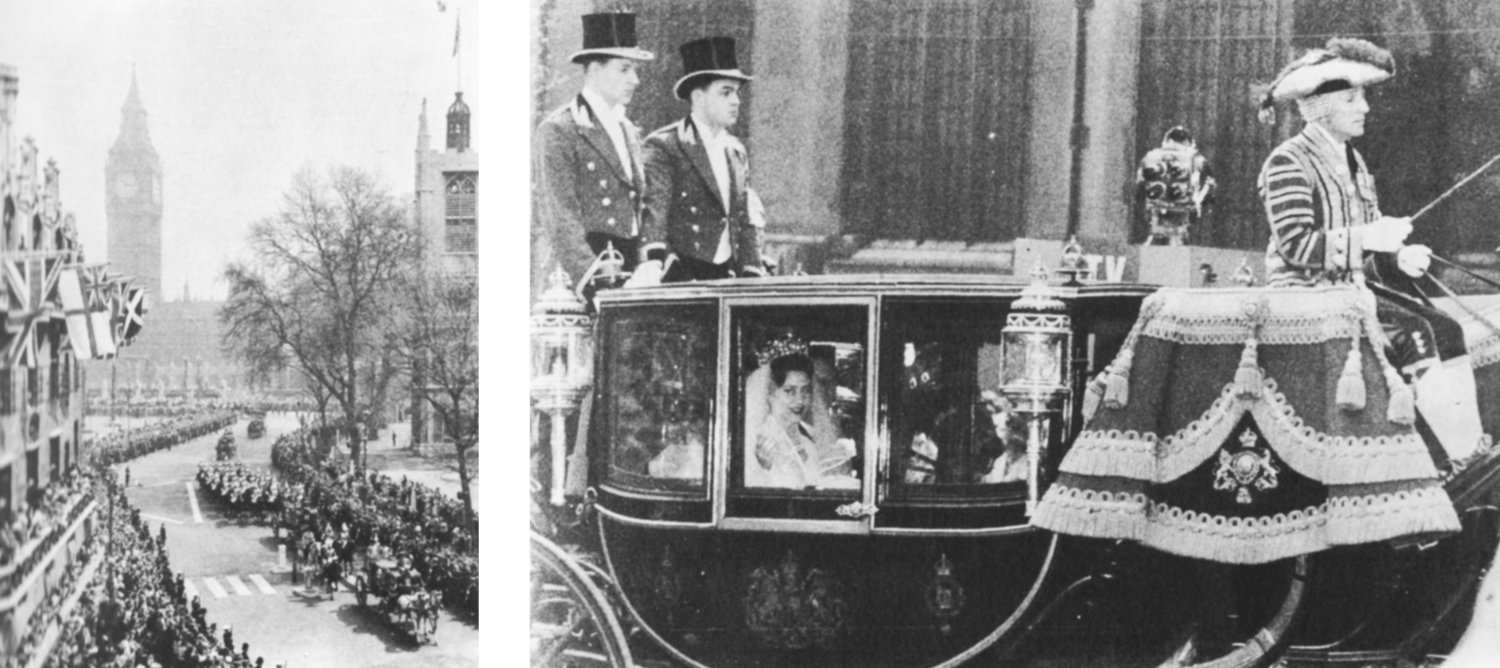

Then, after six hazardous and gruelling years, he finally doffed his war correspondent’s uniform. With twenty other men who had reported the war by typewriter or microphone, in the Birthday Honours List of 1946 he received the OBE.