When Richard died, I had worked with him for over six years as a Panorama colleague, and had got to know him very well through innumerable Monday conversations enlivened by his earthy humour, his caustic comments on Panorama items he disliked, and his endearing love of uninhibited gossip. But I first met Richard not as a colleague but as a rival – this was in 1958 – when I was working for ITV. This gave me my first inside knowledge of his professional skill and his friendly courtesy.

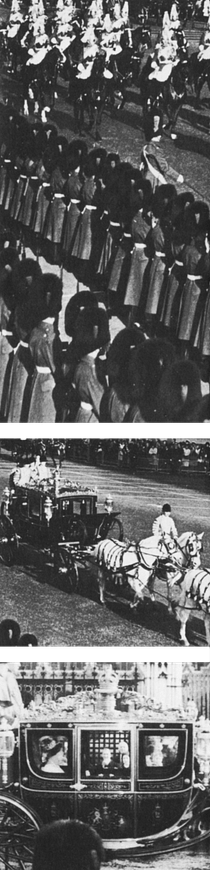

The occasion was a historic one for both television and Parliament. The State Opening of Parliament by Her Majesty the Queen, a ceremony second only in splendour and solemnity to the Coronation, was to be televised for the first time. At half-past nine in the morning I climbed up through a trap-door into a wooden cubicle smaller than a telephone kiosk. It had been installed high up between the Victorian Gothic arches of the House of Lords chamber. The small glass window looked across the golden Throne at the other end. A few feet away from me, in a companion cubicle, Richard Dimbleby had squeezed into his position. He was to provide the commentary for BBC viewers; I was the ITV commentator. ‘Dimbleby v. Day’ was the theme of Press comments, or, as the Daily Express put it, ‘The Gentleman versus the Chap’.

This was an assignment in which practically everything was against me. I was a novice competing with the master craftsman, a man who knew from countless royal occasions every jewel in the Imperial Crown and every stitch on a herald’s tabard. The TV pictures were being provided by the BBC and ‘fed’ to ITV. This put me in the awkward position of having to comment on a sequence of pictures selected by a producer who was following Richard’s words. Supposing, for instance, that Peter Dimmock, the BBC producer, had shown a shot of King George V’s statue and was about to go to a shot of the Victoria Tower. Richard would be saying ‘and there is the memorial to the Queen’s grandfather, the beloved Sailor King’. Dimmock, whose camera instructions were heard on headphones by Richard and myself, would shout ‘coming to Victoria Tower’. At this, Richard would skilfully wind up his remarks about King George V and lead into a shot of the Victoria Power, like this: ‘the beloved Sailor King, George V, whose statue stands across the road opposite the great Victoria Tower’. Meanwhile I would be trying to do the same thing. The difficulty was that though Richard Dimbleby was, like myself, following Peter Dimmock’s cues, the exact moment at which Dimmock put a given picture on the screen would be timed to fit Richard’s words. As soon as Richard got to the word ‘Victoria’, up would come the tower on the screen. The BBC provided me with details of the order and timing of the shots to be taken by their cameras. Even so, it was pure luck whether my words fitted the pictures as closely as Richard’s. It was an exceedingly tricky business to form appropriate phrases with the roar of the crowds and bands in one ear, and Dimmock shouting his control-room instructions in the other: ‘Coming to Horse Guards Arch – where are you, Camera Seven? … Coming to Horse Guards Arch now … Hurry up, Richard …’ with Richard’s commentary somewhere in the background.

Another problem facing me was that of style. Only the BBC had been allowed to install cameras, but the ITV network had been given the right to have their own commentator. It was made clear to me that something different from the Dimbleby style was required. It was not made clear how this difference was to be achieved. How could one be very different in tone from Richard when describing a solemn royal occasion? Yet any attempt to imitate or outdo the master with majestic, flowing descriptions was doomed to failure.

During the preparations and rehearsals I met him several times, and if he regarded me as a somewhat brash and bumptious rival, he did not show it. He could not have been more helpful to me, though the occasion was one of the first big state occasions in which ITV had shared and Richard was naturally determined that the BBC would score a triumph. He never failed to pass on to me any point I would need to know. During my researches I was trying to locate an expert description of the elaborately ornamented throne – on which the camera was to dwell frequently. Eventually it appeared that the most authoritative and detailed description was in Richard’s hands. He readily sent me a copy, with his good wishes.

One tiny incident demonstrated to me his professional skill and experience. It had been arranged during rehearsals that at a certain point in the ceremony the cameras would dwell for a few moments on the pictures along one wall of the Royal Gallery, and I had duly memorised all necessary details of the monarchs or consorts whose portraits might be seen. Alas, when the time came the cameras had, for some unexpected reason, to focus on a completely different set of pictures hanging on the opposite wall. This did not throw Richard in the slightest. Though he did not go into names or details, his commentary flowed calmly on with appropriate references of a general kind. But I was so irritated at the unexpected change of plan that instead of continuing as best I could, I banged down the commentator’s ‘cut-off’ switch and cursed. My ‘covering’ reference came to mind too late and I regret to say that for several silent and embarrassing seconds a portrait of one of Her Majesty’s ancestors, whom I did not recognise, filled the screen undescribed and unidentified. A trivial incident – and one which few people noticed – but it made me very angry with myself at the time, and humbly envious of the veteran’s skill.

Some years later I happened to be doing the BBC commentary on President Kennedy’s inauguration. This was a ceremony which Richard would normally have covered, but for some accidental reason which I cannot recall, the assignment fell to me. He watched the broadcast with a keen professional eye, and the following Monday we discussed it in detail. From the TV commentator’s standpoint the Inaugural had been a chaotic business and my commentary must have revealed this. Richard, however, was full of a fellow professional’s understanding: ‘I could see what your problem was at that point’ or ‘I know exactly what you were up against when so-and-so happened’. And his verdict was very generous, which was typical.

In October 1959 the Dimblebys went to Buckingham Palace for Richard to receive from the hands of the Duke of Edinburgh the OBE which he had been awarded in the Birthday Honours List. He had already been the winner of many national radio and television awards.

Not everyone took to Dimbleby’s prose style, which John Crosby, the London-based columnist of the ‘New York Herald Tribune’, once attempted to convey to his American readers thus:

And now, as the leaves are turning to gold and the glittering draughts of campaign oratory turn sere and yellow in the newspaper files, let us turn our attention to the majestic cadences of Richard Dimbleby’s prose, which may have permanently affected my own and gives even this opening sentence, if I make so bold, a resplendent thunder, a faint but distant echo of Mr Dimbleby’s own glorious, and if I may, and on the whole I don’t know why I shouldn’t say, gleaming utterances. But, my God, Dimbleby, how in hell do you ever get the damned sentences to stop once you get them rolling along like this?