Richard himself received another 500 requests for the poem by Avril Anderson which he read at the conclusion of his commentary:

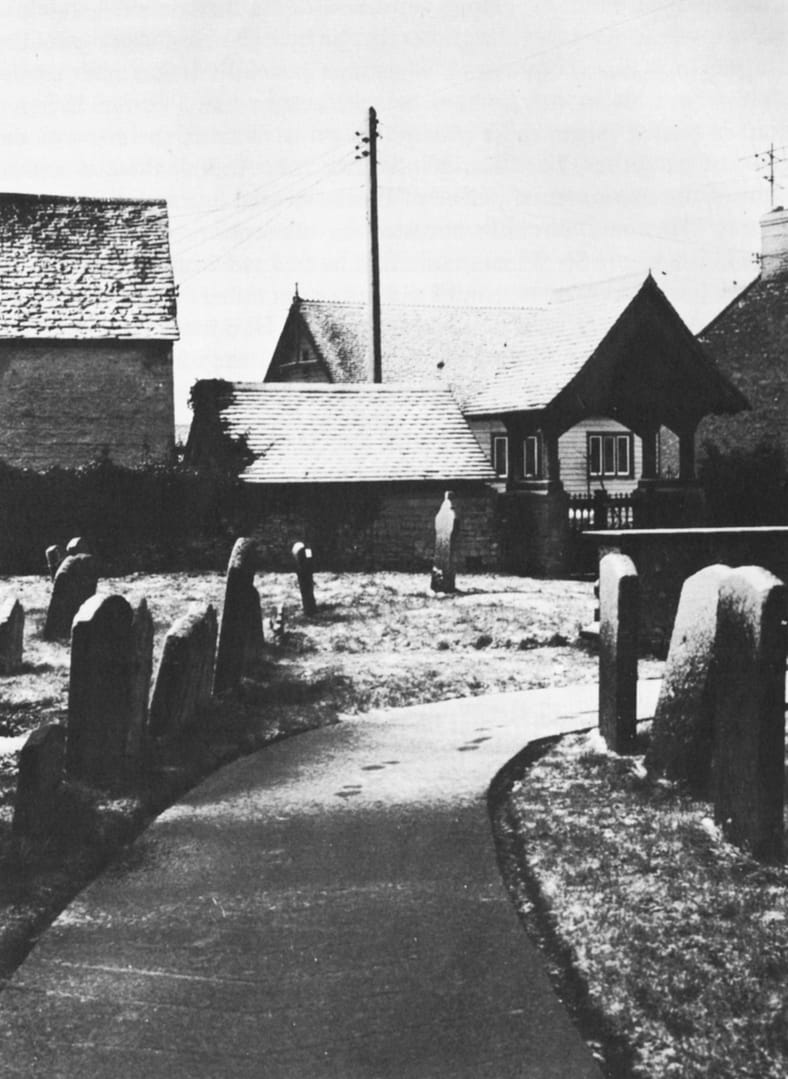

… the village of Bladon, just two miles from Blenheim where the lychgate of the church and the tower of the church can be seen on a winter’s day. It’s close by this church and this churchyard that the Spencer-Churchills lie buried. Not in any lordly isolation, but buried with them down there, John Harry Adams, and Percy Merry, and Kathleen Jones, and William Partlitt, and John Abbott, and Arthur Sawyer, and two little unnamed children aged six and seven. The church itself is as simple and unpretentious as are the graves that lie by it. These the graves of the Churchills – this the grave of Winston Churchill. It lies next to the place where his mother, whom he said was to him like the Evening Star, is buried under those plants that grow. This is the cross of the grave of his father, Lord Randolph Churchill. And all this lies within sight of the monumental palace of Blenheim that a grateful Sovereign gave to Winston Churchill’s ancestor for his services to England, the huge house where Sir Winston said that he took two important decisions – ‘to be born and to marry, and I did not regret either’. Here as a boy he played. As a young man he took the train to Handborough, and a lift on the estate cart up to the Palace. Here he returned in the days of his fame. Here they bring him today to lie forever.

From the Hall of Kings they bore him then,

The greatest of all Englishmen,

To the nation’s, the world’s, requiem

At Bladon.

Drop, English earth, on him beneath,

To our sons and their sons bequeath

His glories, and our pride and grief

At Bladon.

For lionheart that lies below,

That feared not toil, nor tears, nor foe,

Let the oak stand, though tempests blow

At Bladon.

So Churchill sleeps; yet surely wakes,

Old warrior, where the morning breaks

On sunlit uplands – but the heart aches

At Bladon.