Through the eight years I was in charge of current affairs and talks programmes on BBC Television I spent most Monday evenings at Lime Grove. That reconstructed old film studio seemed to acquire a special air of magical excitement on Panorama nights. There was always a knot of schoolboys with autograph books in the darkness outside the main door on the look-out for visitors whose names were in that day’s headlines, or would be in the morrow’s. Sometimes a senior Minister, sometimes an anonymous group would come – for instance, women who were seen knitting throughout one Panorama and then questioned on how much of the programme content they had absorbed. One day in came a box filled with ice, into which a man was locked, and he freed himself during transmission. Mrs Barbara Woodhouse offered to give away to a good home a calf named Conquest, which we watched snuggling down in a pen in the studio with her enormous and beautifully trained Great Dane Juno. The Watford telephone exchange was swamped with eager calls at the rate of 6,000 an hour.

You never knew what to expect. One day it was a French girl of nine who was set the task of writing a poem on London at the beginning of the programme. She was seen writing hard for a while, got up and bounced a ball once or twice, went on writing, and Dimbleby finally put his excellent French to use by translating the charming verse Minou Drouet had composed. Another day there was a full-grown elephant in the fourth-floor studio, carrying a man gently across the floor with its trunk.

When we decided to make Panorama a weekly programme in 1955 I asked my deputy, Grace Wyndham Goldie, to supervise its new look. She immediately set on it that stamp of quality which marked all her television enterprises. It was she who first demanded that Richard Dimbleby should be the new anchorman, and before soon moving off to energise in turn the start of Tonight and then of Monitor she had firmly settled the guiding lines for Panorama: integrity in its coverage of current affairs, showmanship in its intelligent exploitation of the television medium.

The changing team of Panorama reporters have contributed a wide selection of talents. Most have had to be ready (as Dimbleby forecast even during the war for his two roving European reporters) to fly off at a moment’s notice to where news was about to break. All have been interested in politics, some with one foot in it. Some left Panorama for the House of Commons, like Christopher Chataway and Woodrow Wyatt. Some came to Panorama after failing to be elected, like Robin Day and Ludovic Kennedy. Some combined journalism with a political past, like John Freeman and Angus Maude. There were ex-editors from Fleet Street, Malcolm Muggeridge and Francis Williams, and others whose background was essentially in broadcast journalism, Max Robertson, James Mossman, Michael Charlton, John Morgan, Michael Barratt, Ian Trethowan and Leonard Parkin. Others came and went. They were a talented and restless group, with a tendency to wish to leave after a few years, perhaps later to return again. Panorama reporters were welcomed by such world figures as President Kennedy, Pandit Nehru and the Shah of Persia. They were frequently involved themselves in controversy, for Panorama had to be involved in controversy, and they had to prise out cats which various vested interests preferred to keep in the bag.

In Panorama’s whirlpool, as Grace Wyndham Goldie has pointed out, Richard Dimbleby himself always managed to remain at the serene centre, not at the tumultuous edge. He did not want the reputation of a Robin Day or a Malcolm Muggeridge, and so, as she put it, he became on television a kind of living embodiment of stability, a reassuring symbol that somewhere at the heart of disturbance lies a basic kindliness and an enduring common sense’.

The production teams were constantly turning over, as inventive production assistants and producers, trained in the hard school of Panorama, went off to produce new programmes of their own.

Michael Peacock was the first of several editors, each of whom brought some special attribute to Panorama: Rex Moorfoot, Michael Peacock again, after a spell with Outside Broadcasts, Paul Fox, David Wheeler and now Jeremy Isaacs.

Richard Dimbleby remained the one constant factor. He would arrive on Monday mornings and go very carefully through the elaborate studio moves, which were never the same from one programme to the next. A length of film needs to run for eight seconds on a television projector (telecine) before it reaches full speed. An anchorman has to be able to cue the start of the telecine machine and then speak for exactly eight seconds. Dimbleby was impeccable. He would finger his spectacles, indicating the start of the eight seconds, and finish his sentence invariably just as the first frame came up – or if it was late in coming he would spin out his words until out of the corner of his eye he saw the picture arrive on his monitor. He enjoyed demonstrating maps and summarising complicated situations. ‘Let me see if I can simplify it’ he would say, and one felt he was a teacher manqué as well as a surgeon manqué.

His long apprenticeship in radio had made him a master at reading a prepared commentary to a film sequence, and he could get through a last-minute session in the Lime Grove dubbing theatre much faster than most, for his readings were always right first time.

After a day of very careful preparation he changed his clothes and ate a light supper. He would then greet, and set at ease, the important, and the unimportant, and the often temperamental protagonists we had invited to the studio. Dimbleby was invariably an excellent host, and Panorama’s guests were always anxious to meet him. So too were many distinguished visitors to London such as King Hussein of Jordan, who dined with us one night because he wished to see television in action. We took him on a tour of the studios, and finally ended up in Panorama, where a memorable interview took place with the King and Dimbleby, like Johnson and Boswell, each calling the other ‘Sir’ in every sentence.

H.R.H. the Duke of Edinburgh had introduced the International Geophysical Year on television, and reported on his travels in a children’s programme. The first time that he, or any other of the Queen’s immediate family, decided to allow himself to be questioned on a regular current affairs programme was at the hands of Richard Dimbleby.

There were occasions when Dimbleby almost acted as a national Ombudsman, or a restorer of national confidence. When the world was on the brink of nuclear war over Cuba, and Panorama was mounting a special programme, a woman telephoned to say she would send her children to school only if Richard Dimbleby said it was safe. He made a point of saying to an authority in the studio, ‘I am aware that a great many people today are extremely worried and frightened by what has happened, and have some awful feeling that something dreadful may happen quite quickly, suddenly. Do you think there is reason at all for short-term immediate nerves on this?’

There were several occasions when he was game to subject himself to any kind of treatment in the studio, be it an ice-cream tasting contest with Francis Williams to guess which was made with real cream, or being flung around the studio in an aircraft seat on wheels to test the shock of sudden braking, or swallowing a tiny transmitter and picking up the signals from inside his massive frame, or being spun round in a space simulator at the RAF Medical Centre. For the last programme before Panorama’s much needed annual summer break in 1959, he demonstrated the new American craze for balloon jumping from an airfield at Weston-on-the-Green. It was fascinating to watch his considerable mass reduced to nothing as his weight was counterbalanced by a balloon on his shoulders, and Dimbleby leapt ten to fifteen feet in the air and covered the same distance between strides along the ground.

He had his little vanities. One was getting the make-up assistant to black the balding patch on the back of his head, until it could no longer be disguised. In the studio there was always fun with the technical crew. During a programme which demonstrated the gimmicks of the 1964 American Election campaign, Dimbleby opened a bottle of Barry Goldwater Cologne for Men. An electrician chargehand next to him commented on the pungent aroma, and asked if it was coming from him. Dimbleby put the neck of the bottle against the chargehand’s arm meaning to ‘spot’ him, but accidentally poured a large quantity on to him. The electrician washed it off but the smell remained strong. After the programme he declared that when he got home his wife would ask searching questions as to the origin of the perfume. Dimbleby immediately wrote a note on a page of his script:

‘Dear Jackie,

This is to certify that I, Richard Dimbleby, have soaked your husband in Barry Goldwater Cologne. He is concerned in case you suspect him of wrong doings.

Personally I think it improves the brute.

Regards,

RICHARD.’

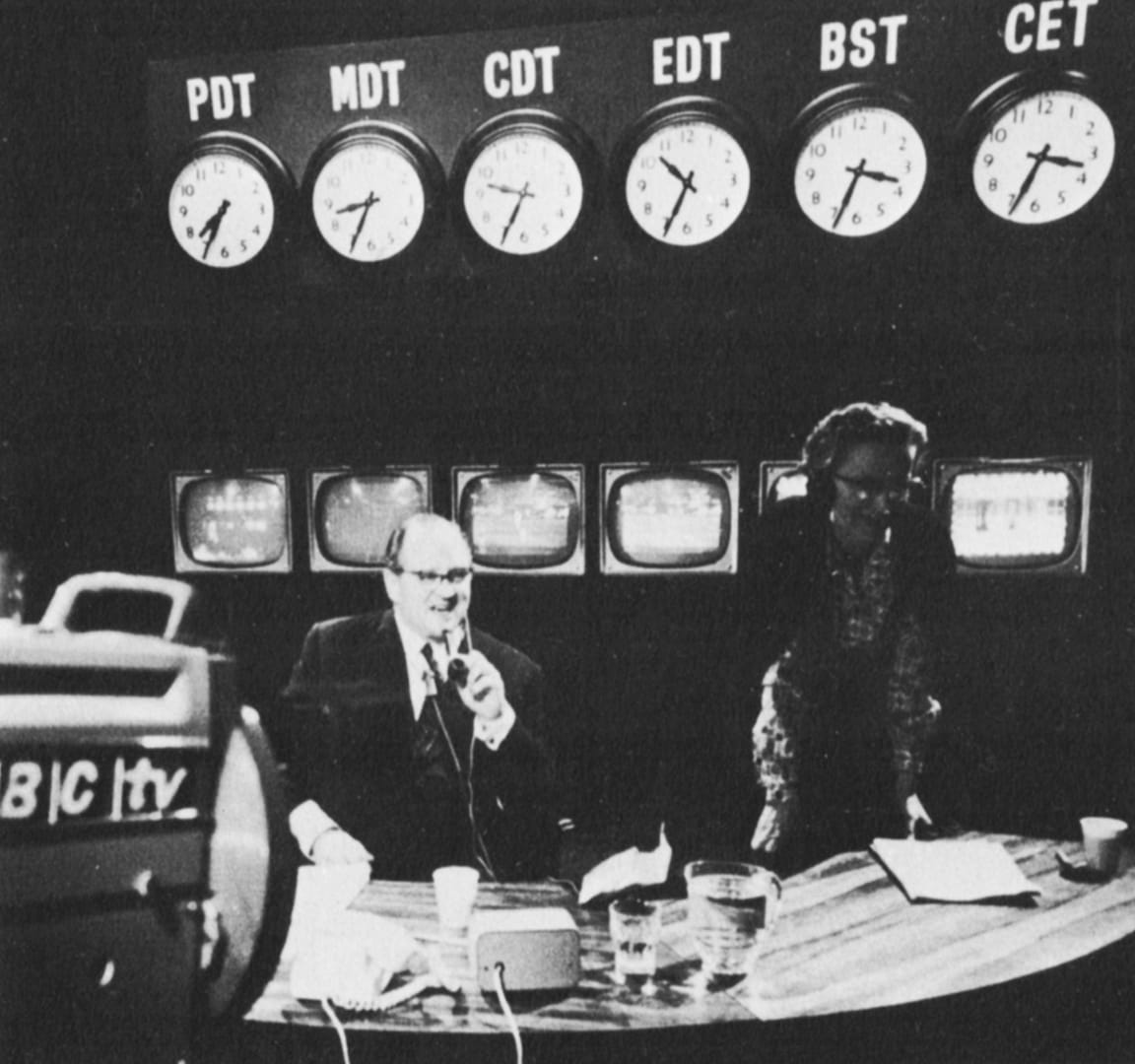

Dimbleby used to keep the studio crews in fits of laughter with earthy stories, mostly unprintable. There was wonderful teamwork, and constant banter, between him and Joan Marsden, Panorama’s regular floor manager. The floor manager wears a receiver on the belt with headphones to pick up the director’s instructions and pass them on to the studio performers. During an edition of Panorama from Sotheby’s sale room which was beamed to America by Early Bird, Joan raised her finger to give Richard the customary ‘one minute’ cue. As soon as he had finished that particular link and a piece of film was running he beckoned her over and said, ‘For Heaven’s sake don’t do that or you will find yourself having bought a picture for £10,000 – “Sold to the lady with the double deaf aid!”.’

She is one of many people for whom Monday nights at Lime Grove have lost something of their magic.