I have always had a feeling that the year 1945 was a turning point in Richard’s life. It was the year in which he saw Belsen, and, as for so many of us, the world could never be quite the same after that outrage to human decency. And Richard was with the first party to go in.

It was a strange and frightening spring for the BBC war correspondents. We had covered the crossing of the Rhine, the last of the big battle set-pieces of the war, and the last occasion when we had to carry the microphone into the front line. I remember trying to do a commentary in the leading Buffalo assault craft as we plunged across the river at night, while next morning Richard was with the gliders that came through a furious storm of flak to make the biggest airborne landing ever staged by the allies. We met on the ground not long afterwards and I remember Richard saying to me, ‘I don’t think I want to see much more of war. I’ve had five years of reporting it and that’s enough for any man.’ I admitted that I had also lost my keenness for front line reporting – in 1945 the end seemed in sight and no one wants to take risks in the last minutes of a battle.

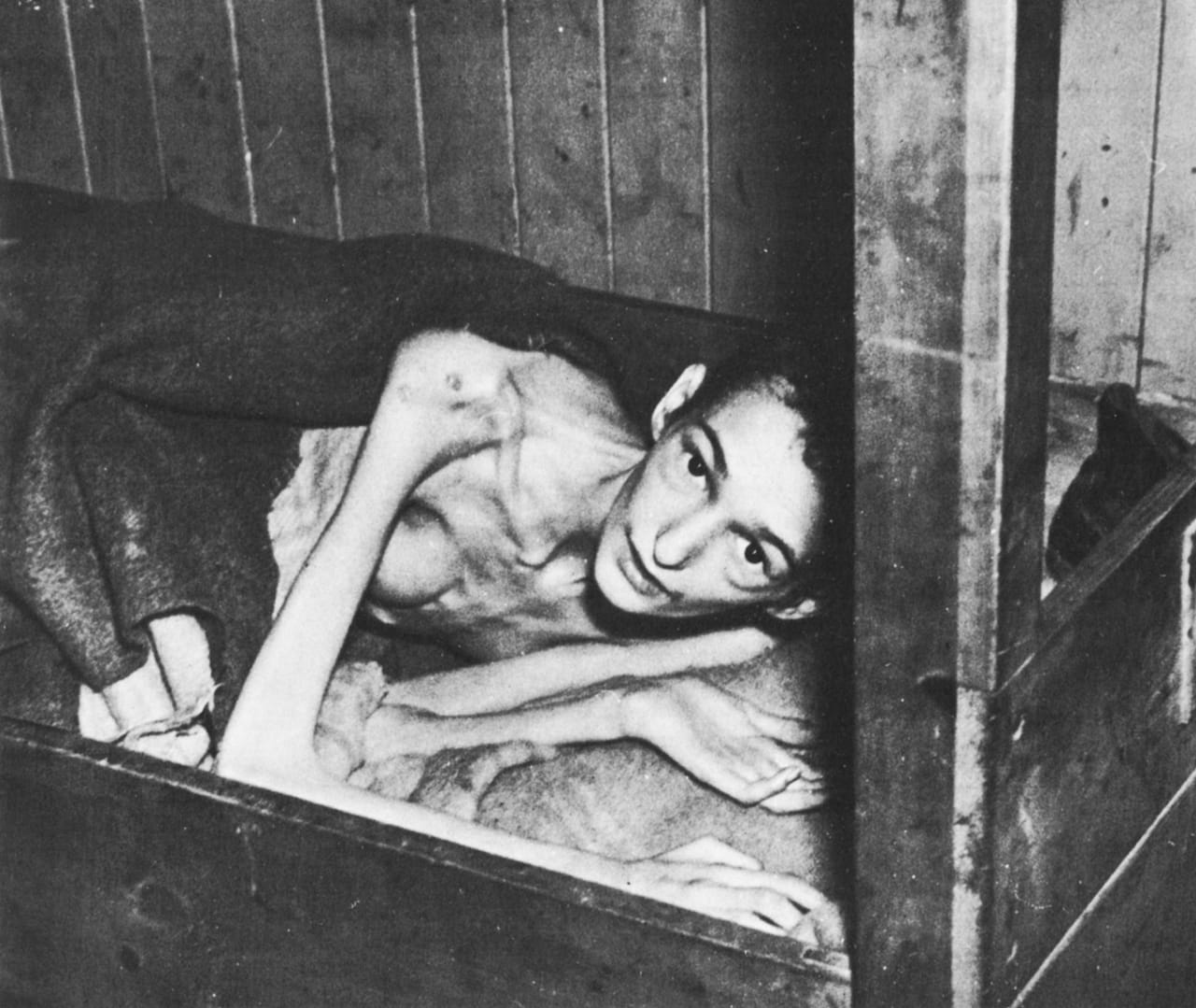

Besides, we were now driving fast through Northern Germany and we were beginning to uncover some of the grim secrets that the Nazis had been guarding for so long – party headquarters with secret documents of the treatment of political opponents, propaganda centres full of the mad fantasies of the Third Reich, forced labour camps with starving Russian prisoners-of-war. But so far we had not found traces of the most notorious of the Nazi crimes against humanity, the concentration camps, the mysterious places to which men and women were spirited away, where they were beaten, tortured, killed for the sole crime of being Jews, Poles, Gypsies, or for not believing in the mad vision of Adolf Hitler. We wondered if the stories about them had been exaggerated. After all, released prisoners tend to play for sympathy and surely not even the Nazis could descend to the depths these stories indicated.

Then, on an April morning which had a deceptive promise of warmth in the air, a rumour reached the press centre; our advancing troops had heard that ahead of them there was a camp at which typhus had broken out and they were pushing out a flying column, equipped with medical supplies, to contact the prisoners. Richard always had the good newsman’s flair for sensing a story. I admit I thought the camp was going to be a normal prisoner-of-war one, and for the last few weeks we’d liberated scores of them. ‘Nothing new here,’ I said to Richard, ‘I’ll come up later.’

When next I met Richard he was a changed man. I spotted his jeep coming down through a narrow road amongst the gloomy pine woods that dot the level North German plain. There was rain in the air and the whole atmosphere of the place seemed dank, depressing. Richard got out and said to me at once, ‘It’s horrible; human beings have no right to do this to each other. You must go and see it, but you’ll never wash the smell of it off your hands, never get the filth of it out of your mind. I’ve just made a decision. … I must tell the exact truth, every detail of it, even if people don’t believe me, even if they feel these things should not be told. This is an outrage … an outrage.’

I had never seen Richard so moved. Until then I had always regarded Richard as a man who would never let his feelings show through his utterly professional surface efficiency. But here was a new Dimbleby, a fundamentally decent man who had seen something really evil, and hated it with all his strength. Did the memory of what he saw at Belsen lie at the back of his mind and give his commentaries on great occasions, his appeals on radio and television, a feeling for the suffering and anxieties of others which was instantly perceived by the viewer? I think it did.

I went on up that dismal road and turned down the sandy track through the pine woods that led to the gates of Belsen. What we saw and felt then is best expressed in the words of the most moving despatch Richard Dimbleby ever broadcast for the BBC: