Dimbleby published his own account of his experiences in Westminster Abbey in the ‘Sunday Dispatch’ five days after the Queen’s Coronation on 2 June 1953:

In all my experience of State ceremonies – and I have described most of them in the past ten or fifteen years for the BBC – I have never known one go so quickly. I think that this was due to the wonderful colour of the scene in the Abbey and because it was changing all the time. There was always something to watch.

I left my yacht, the Vabel, on the river in a police launch at a quarter past five on Coronation morning, and I was in my box in the triforium of the Abbey at 5.30. I sat in the box without a break until 2.30 in the afternoon – nine hours. But it felt like no more than two or three. All my colleagues of the BBC had the same experience. It was almost impossible to believe that virtually a whole working day had passed since we came in.

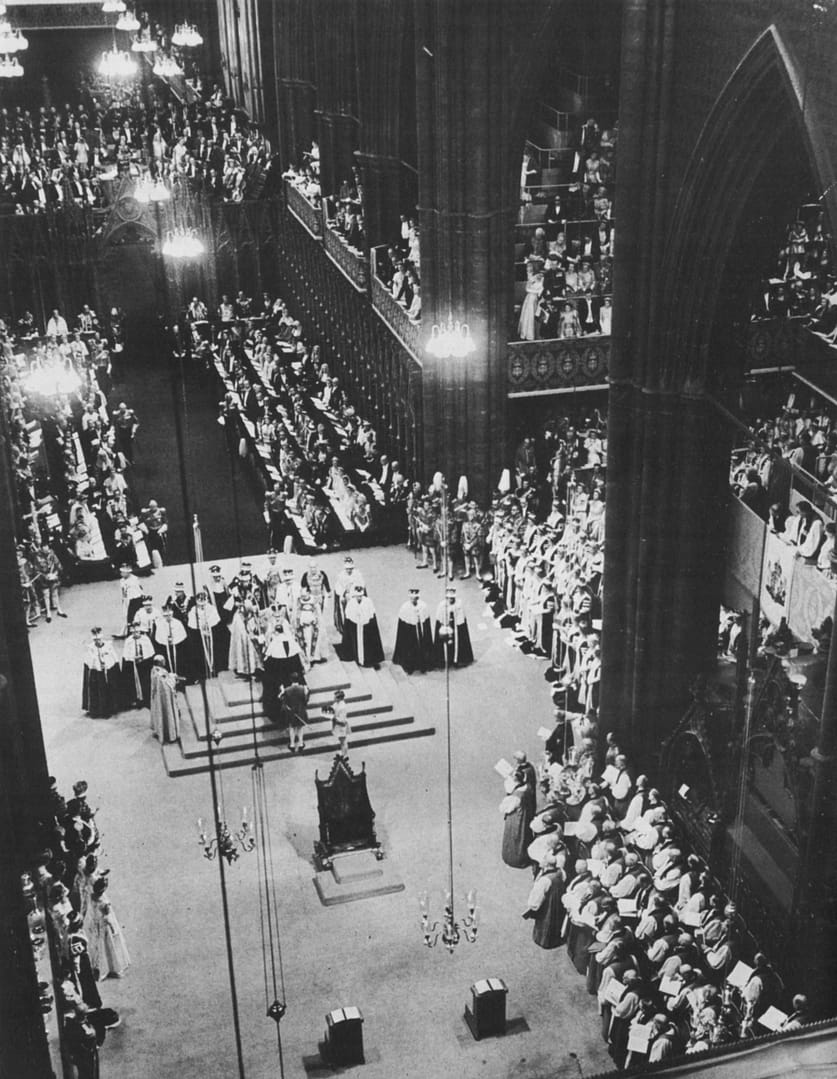

The commentators’ box that had been built by the Ministry of Works for the BBC was a miniature house occupying the two central arches of the triforium, or upper gallery of the Abbey, and in the middle of the eastern end… in other words, immediately behind the High Altar.

This ‘house’, which was so completely sound-proofed that it would have been possible to shout at the top of one’s voice inside it without being heard by somebody standing outside the door, was divided into four rooms.

John Snagge and Howard Marshall, who were the commentators for sound radio, occupied the ground floor left, while the ground floor right was filled by a television cameraman and his camera, of necessity so cramped that he was only just able to sit upright.

On the upper floor the room on the left was occupied by two French commentators, one talking to France for sound radio and television combined (a Herculean task) and the other to French-speaking Canada for radio.

The whole of the ‘coverage’ of the historic ceremony as far as television and sound at home and abroad were concerned came from this minute ‘house’, which was connected with the sound control room in the Dean’s Verger’s room and with the television control in a hut built just outside the Abbey.

The existence of the commentators during the day was reasonably comfortable though rather cramped. Certainly we had an unrivalled view of the whole proceedings, thanks largely to the personal interest taken by the Earl Marshal, the Duke of Norfolk, who climbed up to the triforium one day, a few weeks in advance of The Day, to survey the site and decide on the spot what accommodation should be provided.

One of my outstanding memories of the whole Coronation was, indeed, the kindness of the Earl Marshal. Anyone who believes that this peer, with a castle and big sporting interests, had a sinecure in his – if I may use the expression – stage management of the occasion is utterly mistaken.

Here was a man who carried the entire burden of the arrangements on his own shoulders, who knew every detail, and personally worked out every timetable. I do not think that he could have had more than a few hours’ rest at any time during the eight months preceding this week.

Nevertheless he found time to attend meetings with the BBC and the newsreel organisations to discuss technical details, to go to Broadcasting House to listen to recordings made at the previous Coronation in 1937, to invite the three BBC commentators to luncheon privately so that we could talk over any problems, and to attend the BBC television studios at Lime Grove on the Saturday before the Coronation so that any such minute difficulties could be resolved.

He is also a man of quite tremendous humour. He told me that, having observed some of the staff officers fidgeting during the final rehearsal in the Abbey, he sent them a message ordering them to stop and reminding them that ‘there is plenty of room in the Tower’.

The same could be said of that jolly, entirely natural and charming man, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who has the knack of putting one completely at ease. He confounded me by saying when we met in the Abbey at a rehearsal two weeks ago: ‘What wonderful progress your pigs are making.’

For the moment I thought I had misunderstood his remark until he explained that he had been staying with one of his sons who lives in our village and had seen my piggery and the latest litter. Thereafter each conversation we had in the Abbey was always prefaced by a remark or two about the pigs, to the astonishment of the sundry Officers of State who were standing near.

I cannot deny that I found my task of acting as television commentator for the Abbey ceremony an exacting one, but it was an honour of which I am very proud. The essence of the whole thing is that timing should be precise. The duty of any television commentator is to say just enough and no more, although there are times when the effect of what is being shown on the screen is infinitely greater if it takes place in silence.

Thus, in the Abbey there were moments in the ceremony which had to be left uncovered by speech but which were preceded immediately by ritual which needed explanation. It was, therefore, vital to know exactly how long this ritual took and to prepare a note or ‘rubric’ which fitted that time precisely.

This, I think, was the greatest strain, to speak at a critical moment, knowing that within a second or two something must happen over which one must not speak, or even that Her Majesty or the Archbishop were about to speak.

So thorough had been the rehearsals that we were able to fit this jigsaw together successfully, being caught only once, when the Archbishop proceeded directly to a prayer when at rehearsals he had paused before uttering it. Such details in retrospect may seem very trivial, but it is close attention to them that gives any great occasion its maximum effect. Details, of course, are what one remembers most when looking back on the occasion. I remember when the Duke of Cornwall first appeared by the side of his grandmother, the Queen Mother, in the Royal Box. We had been waiting for this, of course, and for an awful moment I thought that he was in a position in which our cameras could not see him.

His presence in the Abbey for the Coronation of his mother had been so widely publicised beforehand that we never would have been forgiven for not showing him to the millions of those looking in on television. You may imagine my relief when I heard the voice of Peter Dimmock, the television producer at the Abbey, saying in my headphones: ‘I have got a lovely shot of Charles – mention him as soon as you like.’

Then there was the charming paternal attitude of the Bishop of Durham [now Archbishop of Canterbury], who by ancient tradition stands on the right hand of the Sovereign during the whole ceremony. I am sure that millions of people watching their television screens must have seen the continuous glances which he gave the Queen, almost as though he were saying: ‘Don’t worry, my dear… it is going beautifully.’

It reminded me exactly of a father nursing his daughter through some trying ordeal, though in fact the Queen needed no encouragement at all. She had attended several rehearsals, taking part in them herself, and quite obviously knew the whole ceremony.

Though her attitude throughout was devout, indeed humble, since this was largely a Communion service in which she was partaking, I saw her at the moment when the Mistress of the Robes was adjusting the gown of white linen that she wore for the anointing give an almost imperceptible signal with her right hand behind her back that enough adjustment had been made and that she was now to be left alone.

Another moment in the service I found very touching was the homage paid to his wife by the Duke of Edinburgh. The historic form of service laid down for the Coronation demands that the Princes of the Blood and the Peers when kneeling before the Sovereign shall first give their Christian name and title.

For example, the Duke of Norfolk said: ‘I, Bernard, Duke of Norfolk…’. I wonder how many people noticed that the Duke of Edinburgh only gave his Christian name and omitted any title? Was it perhaps because he wanted the Queen to know that he was paying homage to her as her husband and not simply as one of the Royal Princes?

I must also mention the splendid bearing and dignity of Sir George Bellew, who as Garter King of Arms was responsible for a great deal of the detailed ‘stage management’ on the floor of the Coronation theatre. ‘Garter’, as he is known, is a living encyclopaedia on all matters appertaining to State affairs. I have never known him at a loss to answer immediately and correctly the most difficult technical question. Signals which he gave in his capacity as King of Arms during the ceremony for various movements were a model of efficiency and unobtrusiveness.

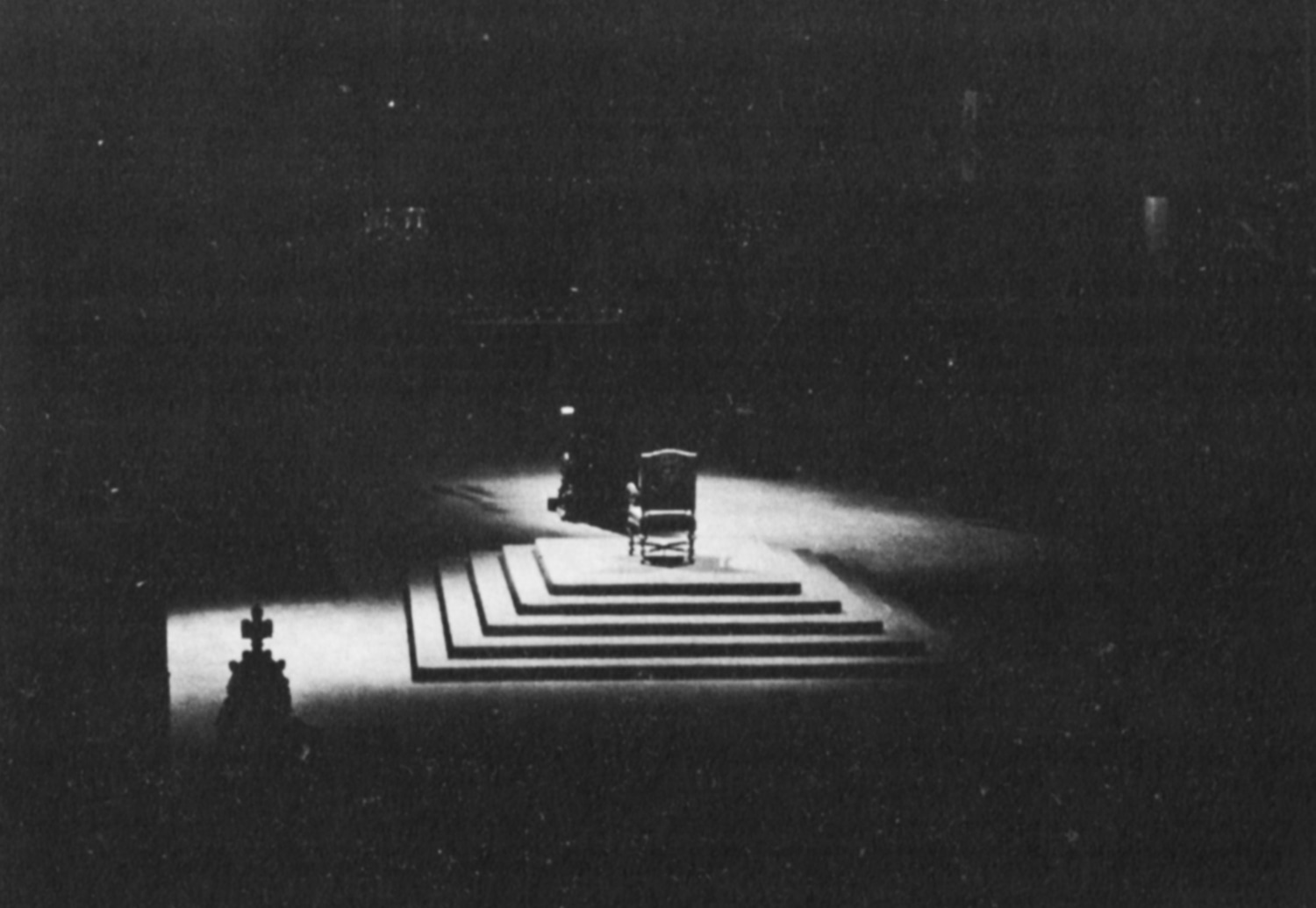

One little thing slightly marred the glorious memories. When I was in the Abbey in the evening while we were preparing the television epilogue which we put on the air unannounced at 11.30 I saw the melancholy sight of the litter left behind by the peers.

It seemed to me amazing that even on this occasion we could not break ourselves of one of our worst national habits. Tiers and tiers of stalls on which the peers had been sitting were covered with sandwich wrappings, sandwiches, morning newspapers, fruit peel, sweets and even a few empty miniature bottles. Let us be fair however, and remember that the peers, many of them elderly men, had sat in their places, some of them seeing very little of the ceremony, for seven hours.

Perhaps it was because the day was so cold that no casualties at all were reported to the ambulance teams hidden away within the Abbey. One herald fainted during the final rehearsal and one page was taken ill. During the actual ceremony no human failing marred the proceedings, in sharp contrast to the considerable casualty list at the Coronation of King George VI in 1937.

During Tuesday’s ceremony I heard an American say: “This is the only country in the world that could stage such a wonderful show.’

His choice of words could be improved upon, perhaps, but his meaning was quite clear. It was a very moving experience, even for one as urgently preoccupied as I was with the details of the occasion, to see a ceremony being performed which would be recorded in the children’s history books 500 years hence.

I felt profoundly conscious that I was seeing history in the making, and, indeed, the whole pageant on the floor of the Abbey moved with a slow irresistible rhythm that seemed to lift it out of time altogether. I thought at one moment as I half-closed my eyes and watched the measured ceremony being carried through that I might be watching something that had happened a thousand years before. In all that time there has been no major change in our Coronations: the lovely robes of the great officers of State, the gleaming swords, the Crown Jewels, the massed assembly of bishops in scarlet and white, and the matchless setting of the Abbey itself – belonging not to one year or to one century but to our history.

This curiously detached emotion was not just the hypnotic effect of a great occasion. During the past two days I have been working with Brian George, who is in command of all recording operations at the BBC, making a permanent gramophone recording of the great occasion.

This has necessitated playing over several times recordings of last Tuesday’s ceremony.

It is an extraordinary thing that the thrill of emotion that I felt when I heard the lovely music and singing and the beautiful spoken words of the Archbishop during the actual ceremony has returned every time that the recordings were played. There is, indeed, a strange quality about the Coronation ceremony. It makes it quite different from any other great occasion in our national life.

There were moments during the ceremony when my emotion must have been obvious to listeners. For example, when I saw the Queen’s Champion so proudly bearing the Queen’s Standard in the procession, a man whose family has defended the honour of their Sovereign without a break since days of William the Conqueror, I found it very difficult to control my voice and speak properly at all.

John Snagge, in the adjoining box, told me that he felt precisely the same emotion.

I believe that we as a nation have done ourselves a profound service by showing to the world how unchanging are the traditions and pride which are our foundations. Visitors from abroad who were in London on Tuesday were envious of everything they saw, and none more so than the Americans – a race of such vitality but so lacking in tradition – who know that they must wait a thousand years before they can show the world anything so significant or so lovely.

I have never been so tired as I was when I finally left the Abbey at half-past midnight on Tuesday – seventeen hours after I entered it. I have never felt so acutely the strain of describing a great public occasion, and I have never before had such a feeling of nervousness and anxiety before the day began.

But I have never been so proud or so glad that I was able to contribute in a small way to history, even to making a fragment of history, because this was the first time that the Coronation of a British Sovereign had ever been seen as it happened except by the privileged few in the Abbey.