Many of the memorable Dimbleby broadcasts depended for their raw material on a flow of news – events such as Budget Days, major Parliamentary debates and above all, of course, the Elections from 1955 onwards. When I was in charge of the intake and channelling of news on such occasions I had my own special reasons for admiring and being grateful to Richard – as well as feeling deeply impressed, like everyone else, by all his other outstanding qualities on the job.

He had a thorough respect for the news facts of whatever he was presenting, and he was always prepared to take any amount of trouble in this cause. Often I’ve handed him a ‘flash’ reporting, say, the latest point in the Budget – on a strip of tape from the news agency teleprinter, with its own specialised abbreviations and with some annotations in hasty handwriting. Never any cause for anxiety: everyone could be absolutely confident that Richard would find his way through it all – and link it into its right context. The same, only more so, with Election news. Once, during a morning lull before the next spate of results, we were giving some news agency corrections to their original voting figures: nothing affecting the results – just a few emendations for the record. In one seat with a large majority there was a correction giving a losing candidate one more vote. I put this correction at the bottom of the others with a note on it: “This might amuse you – no need to bother with it though!’ Not at all: when Richard came to it, he gave the revised figures and added: ‘Our apologies to the voter in this constituency whose vote I’m afraid we overlooked.’

One reason for this scrupulous regard for facts and news – however tense and exacting their presentation – was, I always felt, that Richard never forgot the beginning of his career as a news man.

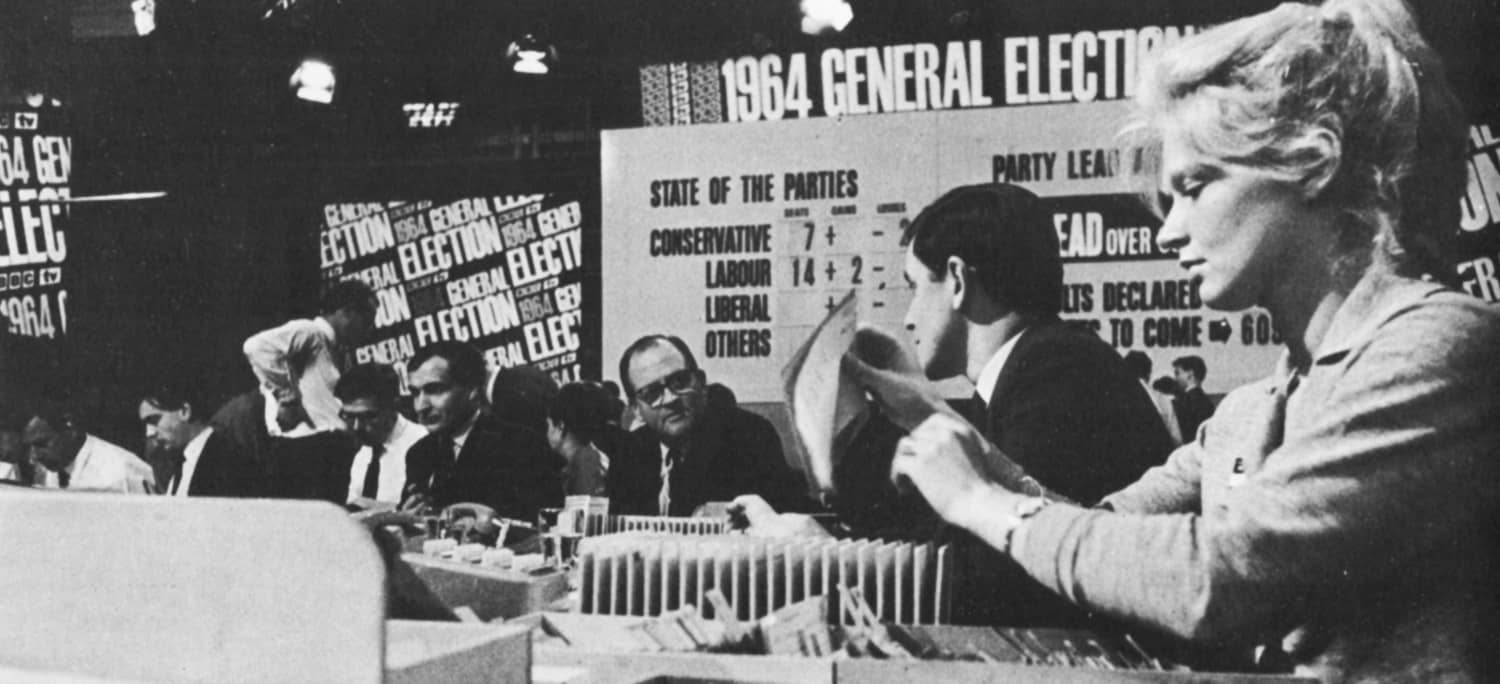

Ian Trethowan described Dimbleby’s astonishing displays of mental and physical stamina on General Election nights in a tribute published in the ‘Sunday Times’:

Others might wilt, Richard kept indefatigably brisk. He had his own political views, but he made no claims to being a political animal. This was not necessarily a liability: at times he could cut through the maze of psephology with some devastatingly simple but appropriate plain man’s question.

To those who worked with him, on those and other nights, any picture of him as humourless was ludicrous. Of course, he relished the pageantry and the aura of the State occasions. But at work, out of the camera’s eye, he could be boisterously funny. In technical rehearsals, he would ease the tension by ambling cheerfully round the studio, joking with the studio crews, clutching a sheaf of indecipherable notes, getting himself caught up in microphone cables, until one wondered what on earth would happen ‘on the night’.

Of course, ‘on the night’ one saw that every move had been carefully docketed away in his mind – and whenever anything went wrong, he was reassuringly certain how to put it right.