Unknown to viewers and to most of his colleagues, from 1960 for over five years Richard Dimbleby lived with cancer. His doctors and family helped the ‘Daily Mail’ to reconstruct those five years to show how living with cancer need not be impossible:

It was early in 1960 when Richard Dimbleby first noticed he had a swelling. It wasn’t much and it wasn’t painful and he was a busy man.

Monday was a fourteen-hour day working on Panorama. Tuesday was spent at Richmond with his newspapers until the evening, when he did a Twenty Questions broadcast. Wednesday was spent working at home. Thursday and Friday he was at Richmond again, working on his newspapers.

Often he was out all day Saturday on extra jobs. He ran two film companies producing industrial films.

Richard Dimbleby was a very busy man. He ignored the swelling.

But by August 1960 the swelling had increased considerably though it still gave no pain. Dimbleby thought it best to go to his local doctor.

His doctor examined him and was in no doubt what was wrong. As he looked out of the window, wondering how best to break the news, Dimbleby said to him: ‘You needn’t tell me what it is. I know.’

Richard Dimbleby’s family and his doctors have made available the history of his case to help combat the general fear and ignorance of the disease. Many doctors believe the fight against cancer is being frustrated by the public’s treatment of it as a ‘taboo’ subject.

This is the story of five salvaged years; of what a man can achieve despite the disease; of how fear, even in a very bad case, can be overcome.

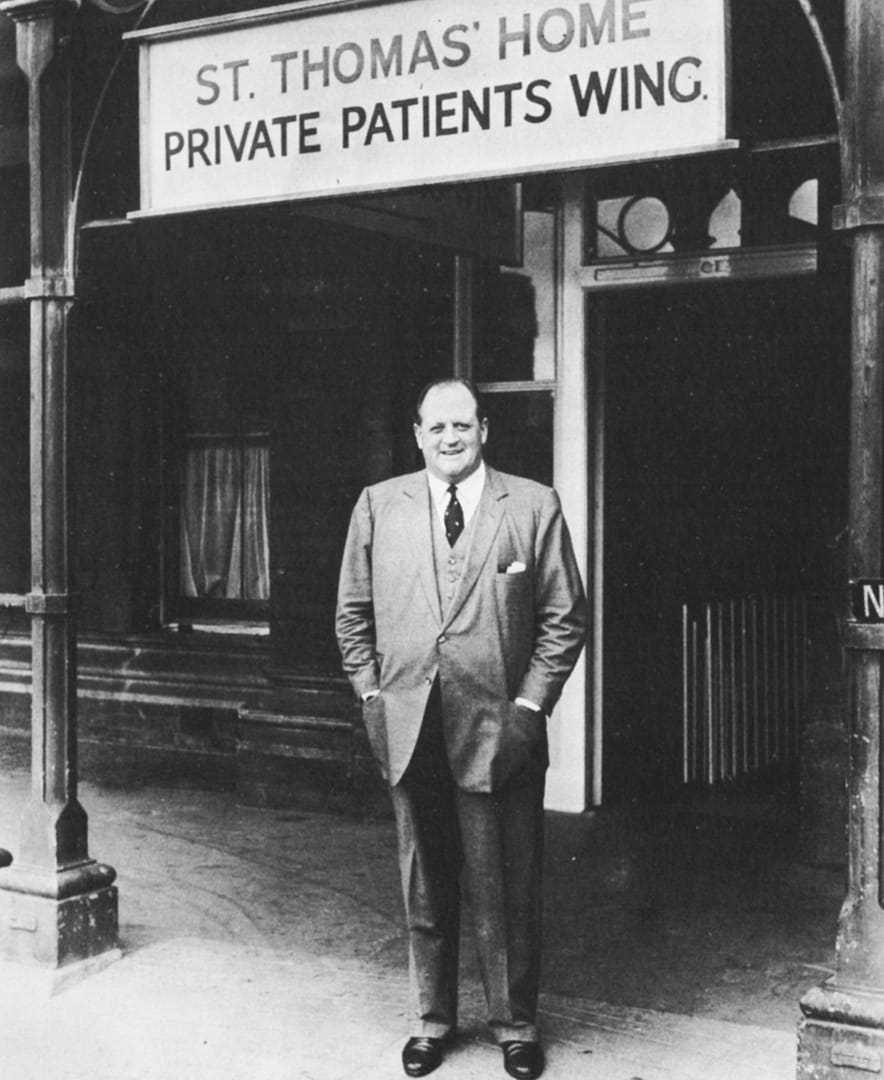

Richard Dimbleby went into St Thomas’s Hospital, London, on 15 August 1960, and was operated on the following day. The chances in favour of a complete cure at that moment were four to one – provided the original growth had not started to spread.

After the surgeon had removed the lump Dimbleby was examined carefully. He was a big man – 18 st. 7 lb. at the time – and the urologist on the case, Mr Ronald Robinson, found it difficult to feel anything under the fat of the abdomen.

But, under an anaesthetic, a mass was felt to the right side of his abdomen. The original cancer had already spread along the lymphatic glands to a new site.

The doctors decided to tackle the secondary growth with a five-week course of radiotherapy. The course of treatment began on 1 September at St Thomas’s, under Dr Ian Churchill-Davidson. Massive destructive doses of X-rays were directed at Dimbleby’s abdomen five times a week.

Five days after the treatment began Richard Dimbleby was on television to introduce a new series of Panorama. The following day he was on the radio, chairing Twenty Questions.

The affected glands shrank. On 3 October Dimbleby went in for his last dose of radiotherapy treatment after appearing on that night’s edition of Panorama. The second round in the battle seemed to have been won.

By this time the disease had become Dimbleby’s special subject. He was learning all he could about it. He arranged to see demonstrations of the machines used in treatment. He listened to all the theories about what caused cancer and discussed cancer research in detail.

His interest was insatiable. After the final treatment Dimbleby went off for a drink with a few of the hospital staff – it had become a custom and they went either to the local pub or the staff canteen – to talk some more about cancer.

The next day he was back at work at the newspapers in Richmond and he remained well and fit in every respect for the next nineteen months.

From time to time Dimbleby revisited St Thomas’s for detailed examinations – all aimed at detecting the first signs of any new growths.

He was able to work at his normal pace. In early November 1960 he went to America for Panorama, came back in time for the Festival of Remembrance Service and the Cenotaph outside broadcast for television; in December he covered the royal wedding in Brussels; in April 1961 he went to Moscow; in May he went to Rome and Naples to cover the Queen’s visit.

It was on 2 May 1962 that Dimbleby complained of a dull ache in the upper reaches of the back. He went into St Thomas’s, where the radiographs revealed that the glands were enlarged alongside the vertebrae and in the structure that stands between the lungs.

Another course of radiotherapy began. On 2 May and 5 May both areas were given radiotherapy treatment. On 7 May Dimbleby was on television as usual introducing Panorama. On 9 May he was back for another dose of radiation.

Once again the glands that appeared to be affected by cancer reverted to their former size.

The pattern of Dimbleby’s life continued uninterrupted. Before the end of the month he was in Sweden for a special edition of Panorama. He covered the Trooping the Colour ceremony, the Middlesbrough byelection, the first Telstar broadcast, King Olav’s visit to Scotland and the funeral of Queen Wilhelmina. For nine whole months he remained free of trouble.

However, in March 1963 Dimbleby began to have pain in the lower portion of the back when he was standing a lot. X-rays showed growths in the second and third lumbar (loin) vertebrae, and a further abdominal examination under a general anaesthetic on 14 March showed a recurrence of the enlargement of the glands in the earlier site in the belly.

Between 15 March and 29 March the abdomen was treated with radiotherapy, though the treatment did not prevent Dimbleby appearing as usual in his chair in Panorama.

During this period of treatment Dimbleby was given a general anaesthetic each time to reduce the risk of radiation sickness which might have resulted from the concentrated dose of radiation.

It was usual for Dimbleby to have his radiotherapy treatment on Friday evenings whenever possible. This gave him the weekend to rest in – radiotherapy treatment may have a temporary weakening effect on some patients – before Monday’s exhausting day on Panorama.

He had by now become adept at his own diagnosis. When he felt a pain he was always able to work out how the cancer had travelled from the last known site to attack the new area. Each time the doctors only confirmed his own diagnosis.

In this way, by taking a deep interest in what was happening to him, Dimbleby was coming to terms with his illness.

Dimbleby had already undergone two of the main types of treatment for cancer – radiotherapy and surgery. The third main method – hormone treatment – is mostly used in treating cancer of the breast. All these forms of treatment have advanced substantially in the past decade.

Surgery: If the growth is visible, accessible and reasonably circumscribed, it can be cut out. The great forward strides in the techniques of surgery and the use of antibiotics, transfusions and better anaesthetics have made success possible in operations that could not be attempted ten years ago.

Radiation: Certain forms of radiation cause cancer, making groups of body cells behave in the erratic way that is the characteristic of cancer. But massive doses of radiation destroy the imbalanced cells, curing the cancerous growth.

Many of the enormous machines now used in radiography rotate about the patient so that the target is always being hit from a different angle, in order to spare the skin and healthy tissues in the track of the beam. The patient feels nothing during treatment, needs only to rest for a while afterwards.

By the time of the third spell of treatment Dimbleby had been living with a particularly virulent form of cancer for three years. According to the mythology of cancer he should have been dead long before or, at least, in great agony.

In fact, at this stage, it was still possible Dimbleby might be completely cured.

Radiation and surgery techniques have developed to the point where much pain can be relieved, even when growths are too widespread or advanced to be cured. When enlarged glands, for instance, start pressing on sensory nerves, they can be irradiated sufficiently to dispel pain if not to cure.

From March 1963 until January 1965 Dimbleby had no sign that he was not free of the disease.

He went about his business with great vigour. In that period he covered Princess Alexandra’s wedding, the State visit of the King of the Belgians, the lying-in-state of Pope John, President Kennedy’s visit to Germany, the Coronation of Pope Paul, the State visit of the King of Greece, the service at Westminster Abbey for the death of President Kennedy, the Pope’s visit to Israel, special editions of Panorama from Paris and Germany, from Canada and Luxembourg, the opening of the Forth Bridge, the American election.

But in January 1965 Dimbleby began to get pains in the lower part of his back and numbness in his right flank. Radiographs showed that the eleventh and twelfth dorsal vertebrae had collapsed through destruction by secondary growths.

Between 15 January and 9 February he was given three sessions of radiotherapy, which relieved the pain. Also between 15 January and 9 February he appeared each Monday on Panorama, covered Churchill’s lying-in-state and the State funeral, and appeared in a number of programmes of reminiscences about Churchill.

Despite Dimbleby’s refusal to give in or to ease the pressure of his work through the next six months, this period was in fact the beginning of the end. The occurrence of growths was beginning to accelerate. Further secondaries were found in his diaphragm, his back and ribs.

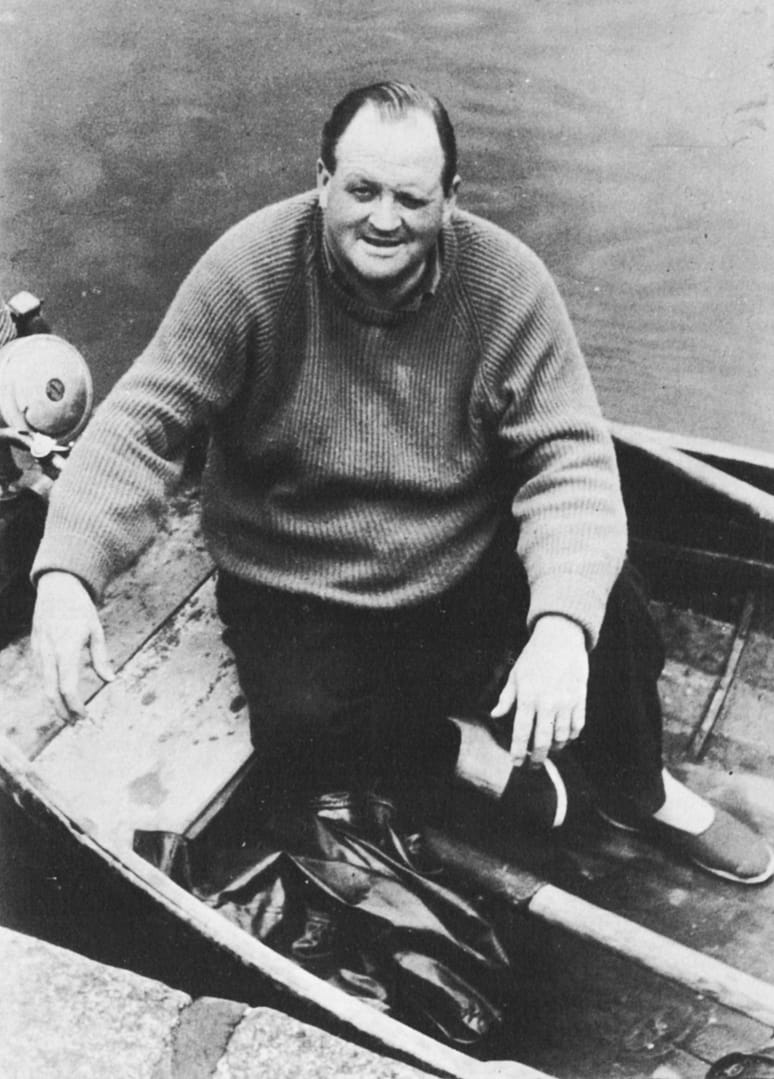

Yet, an incident in the summer of 1965 shows that even at that late stage Dimbleby found the disease neither physically intolerable nor nerve-racking. He went off on his summer holiday feeling, as he said, ‘as fit as a fiddle’.

The Dimbleby family together with Churchill-Davidson, now a close friend, went boating in Devon.

One day off Dartmouth they ran into a nasty storm. It was a fearful moment – for the doctor.

Churchill-Davidson had already warned Dimbleby to be careful of falling while his spine was still in a weak condition. A fall could have meant instant paralysis.

David Dimbleby turned the boat into the 8 ft waves to avoid being swamped, but it was lifting sickeningly over them, then slapping hard down into the troughs between them. Richard Dimbleby stood in the wheelhouse, holding the rail, riding the waves on his tiptoes. And behind him, Churchill-Davidson’s face turned white.

As the boat lifted up and down, Dimbleby nudged his son, indicated the anxious doctor and winked.

When they got into harbour Dimbleby apologised to Churchill-Davidson for the rough ride he’d been given and said he was sorry if he’d been made seasick.

‘I wasn’t sick,’ replied Churchill-Davidson, ‘I was just worried about you. But if your back can stand that it can stand anything. I shouldn’t worry about falling any more.’