Few knew these qualities more intimately than Antony Craxton, who produced more than a hundred major outside broadcasts with Richard Dimbleby, and was his ally in countless battles with the authorities to secure proper facilities for television to cover public events:

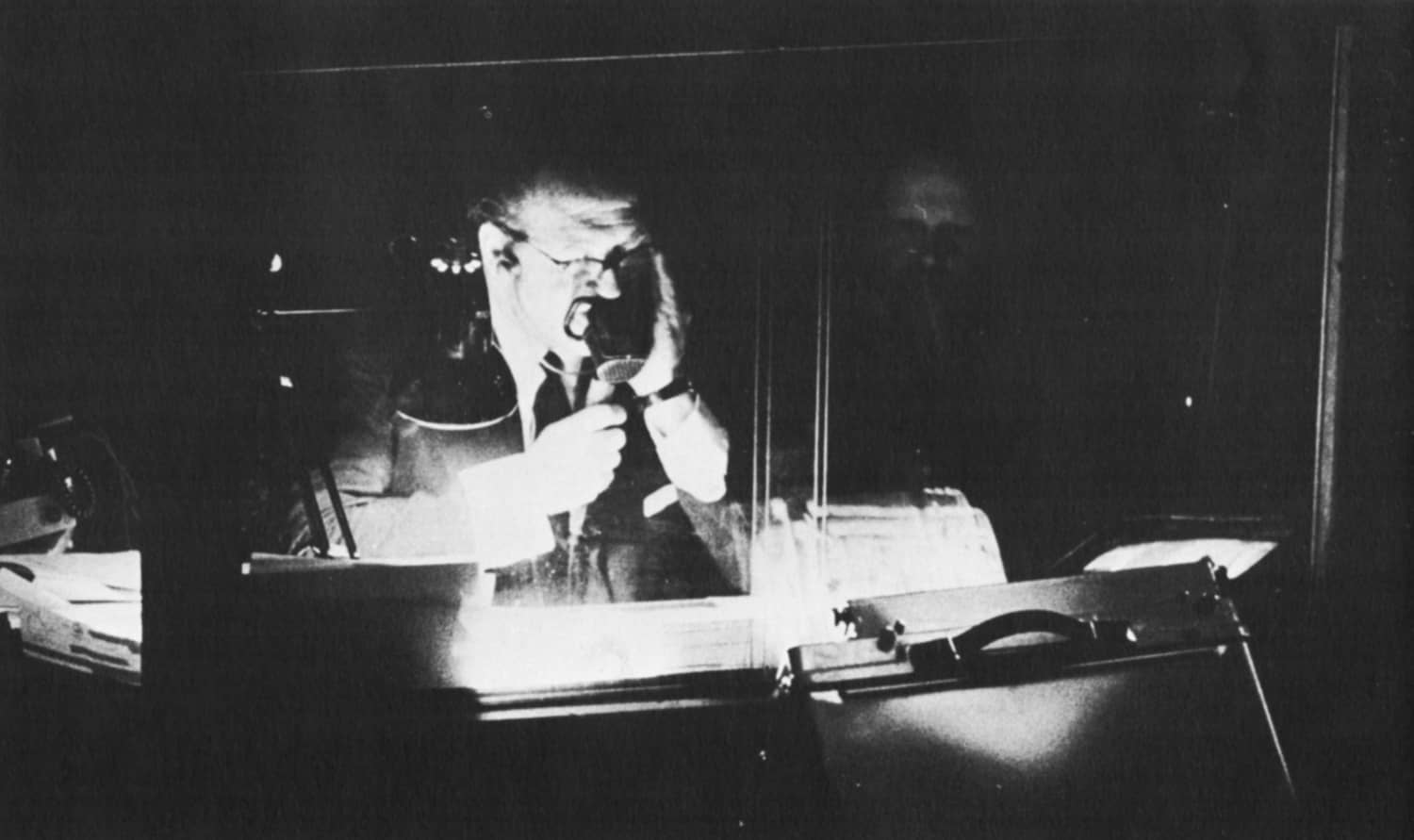

Few people have any conception of the complexities a television commentator faces on a large-scale outside broadcast. One should think it difficult enough to describe events taking place in sight – which they very often are not – while at the same time watching the same events on a television screen. But in addition to this, a commentator has to wear a pair of headphones, through which he can hear in one earpiece the sounds of the event – the band, horses’ hooves, etc. – and in the other the producer giving to him and the many cameramen detailed, involved instructions. Thus, while describing solemn events of a State Funeral, for instance, the poor commentator will be getting constant interruptions to his train of thought. He virtually has to have a split mind, which can keep a fluent commentary going while at the same time absorbing information from the producer which will be essential to him as the broadcast proceeds. Moreover, the instructions the producer gives to the cameramen are equally important to the commentator, as they often forewarn him of what pictures are being planned and which he can then be ready to describe.

For Richard Dimbleby, these difficulties were an integral part of the job of commentating, and so supreme a master of his craft was he that never did they prevent him from giving of his best. Very often when I was the producer I got carried away and used to give my own commentary as I switched from picture to picture – a commentary which, of course, Richard could hear all too clearly – putting words into his mouth. This must have caused him embarrassment on occasions, as he often pulled my leg about it, but at no time in the countless outside broadcasts we undertook together did he lose control of himself, and there were many occasions when the conditions under which he worked would have daunted the brave. Snow, torrential rain, suffocating heat, Richard suffered them all with a philosophical outlook which made him the great professional he was.

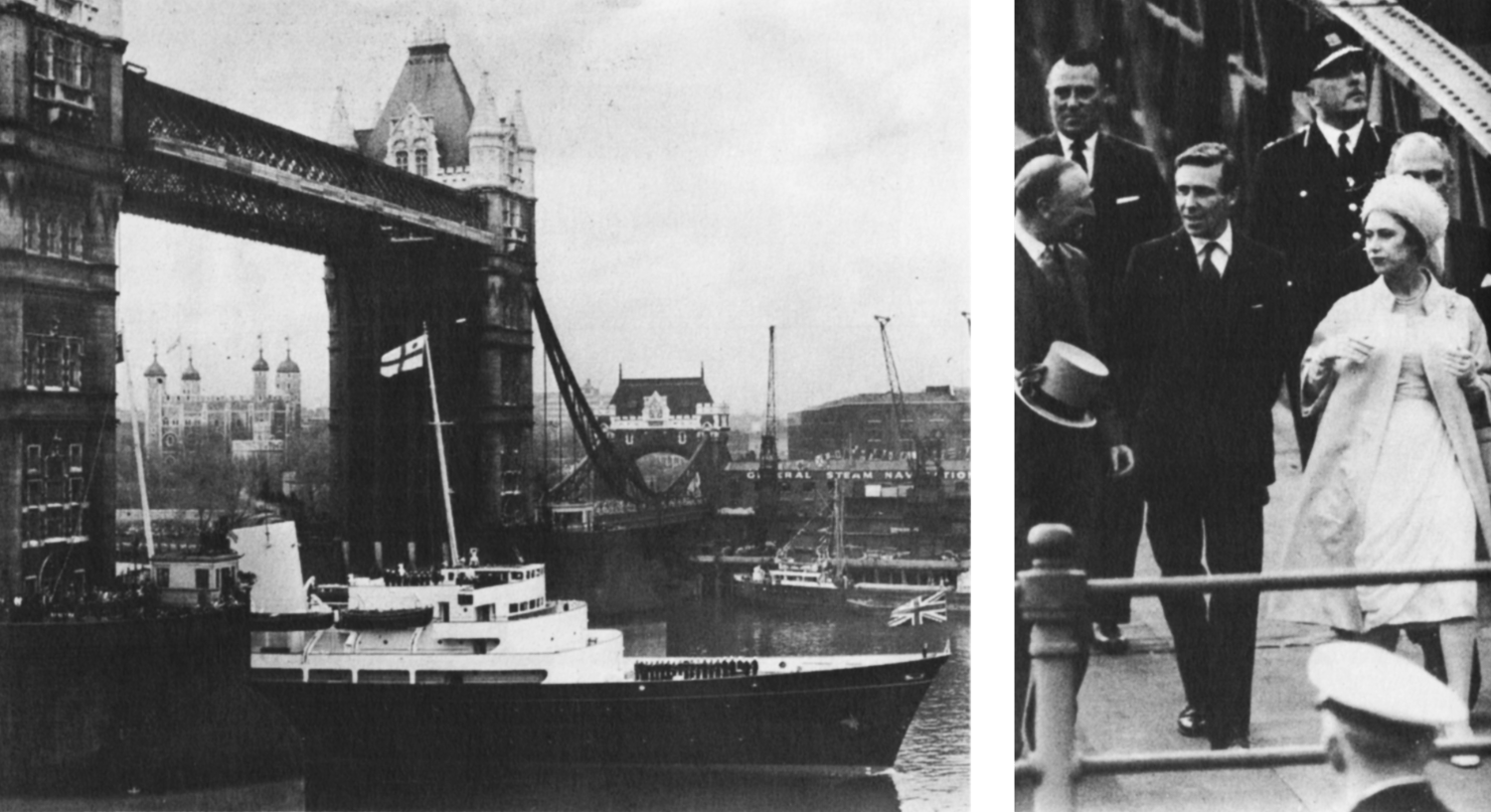

One occasion which challenged even Richard’s powers was the departure of Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon on their honeymoon on 6 May 1960. Richard and I had left Westminster Abbey almost immediately after the marriage service had finished, to journey to the Tower of London, from where the Royal Yacht Britannia was sailing. We had decided to go on the air as the Royal couple left Buckingham Palace, and to fill the twenty minutes the journey to the Tower was expected to take with a planned sequence of pictures from the four Tower cameras. Little did we think that the twenty minutes would be more than doubled before the car arrived. Having completed our rehearsed sequence, we searched for visual material to interest the viewers while they waited: the Tower itself, the Bridge, the jetty, the Yeomen Warders, the Britannia of course, the launch, the skyline of London; every possibility was used. The most remarkable aspect of this unexpected marathon was that Richard wove his commentary into a masterpiece of continuity, so that few people realised that what was being seen and said had not been planned in great detail beforehand. Unrelated subjects and objects were somehow, by Richard’s description, made into a pattern that at once seemed natural and flowing. Towards the end, after the marathon had been in progress some fifty minutes, Richard did show some impatience towards the three or four helicopters circling noisily overhead, and which must have seriously disturbed his concentration, seated in the open as he was. He confessed to me afterwards that he had exhausted his almost inexhaustible fund of information about the scene, and was ready to break into silence at any moment.

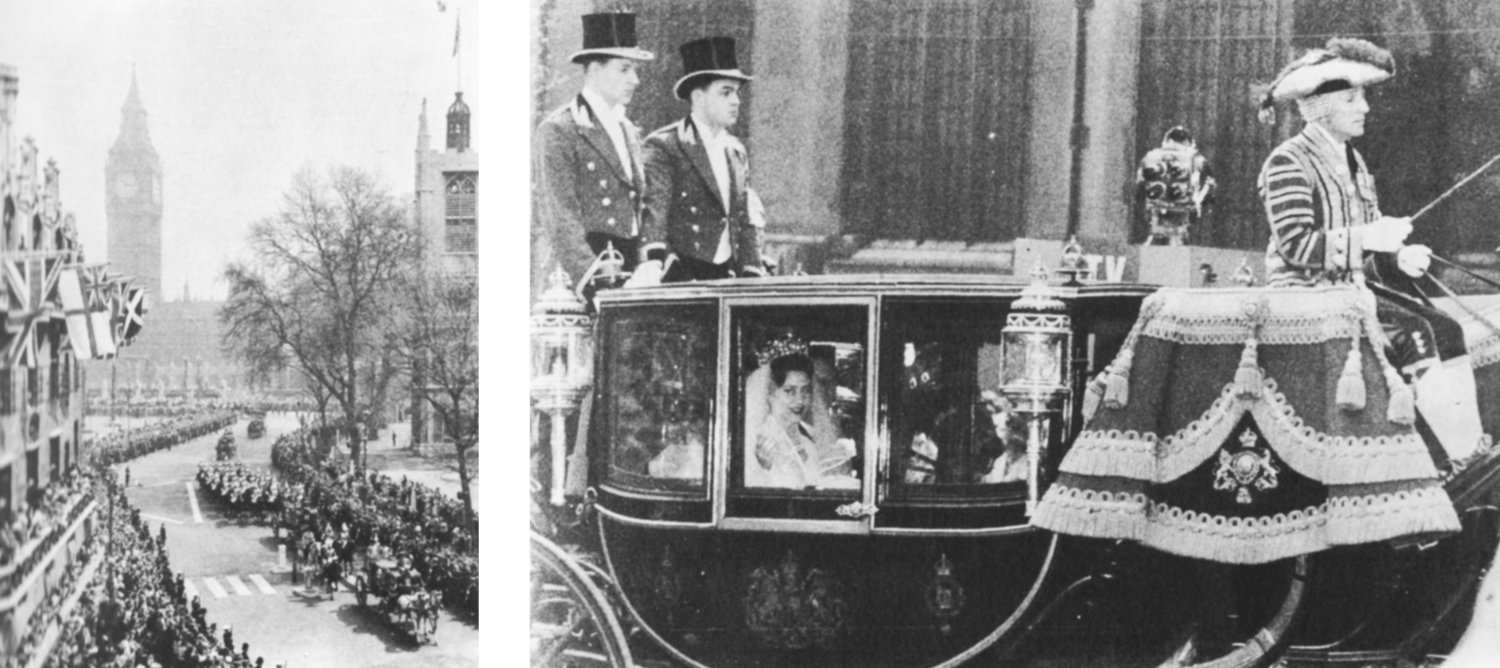

I also vividly recall the opening of the Wedding broadcast. Richard had forgotten that instead of beginning, as originally planned, at ten o’clock, we had decided, for technical reasons, to start five minutes earlier. He was due to open our transmission, in vision, on the lawn outside the North Door of the Abbey. Two minutes before time I noticed that he wasn’t at this camera position, and asked where he was. I was extremely alarmed to hear from a cameraman in the Abbey that he was strolling quietly down the Choir checking seating arrangements, oblivious of the urgency of his presence outside. The only way to get him to the start on time was for the cameraman to startle the distinguished assembled company by calling out to Richard from his lofty position in the Abbey and indicating the need for some haste. Richard arrived a few seconds before the broadcast began, and no viewer would have guessed from his opening remarks that he had run the last fifty yards or so.

Some years earlier I remember an occasion when the usually meticulous Royal arrangements went wrong and caused us acute embarrassment. It was the unveiling by Her Majesty the Queen of the Merchant Navy Memorial at Tower Hill in November 1955. The Memorial is sunk below ground level and consists of a central area with two small side alcoves. In order to get a television camera into one of these wings we had buried a cable at an early stage of construction so it would not look unsightly on the day. As the photograph shows, the camera, on a movable four-wheeled truck, was tucked away in the wing, together with the choir, and almost completely filled the area. The Queen, on her inspection of the Memorial, was due to walk across the front of this alcove, but to our consternation the architect escorted her into it to one side of the choir, and thus out of sight of our cameras. We knew that it would be virtually impossible for Her Majesty to walk right round the alcove as our camera would block her progress. All we could do was to move the camera forward on to the grass, knocking over military band music stands in the process, and subsequently to heave on the submerged cable and, in so doing, lift the flagstones, in an effort to allow the Queen room to squeeze through. My panic-stricken instructions to the cameramen, all of which Richard could hear only too well, did not prevent him from calmly describing the scene, well aware of the predicament we were in. He conveyed nothing of this to the viewing public.

At Princess Alexandra’s wedding on 24 April 1963, instead of using a number of different commentators, which was customary when our cameras were ranged over a wide area, I decided to break new ground and use Richard alone. He was in a sound-proof box in our central control room at the Abbey, immediately behind my position overlooking all the twenty or so monitor screens. The advantages were enormous. Richard could see, as I could, exactly when events were about to happen at Kensington Palace, Clarence House, or Buckingham Palace, as well as along the route and inside and outside the Abbey. This meant that he could work far more closely with me. For instance, I could tell him over his headphones to watch the Kensington Palace picture and that, as soon as Princess Alexandra stepped out from her home, we would switch to those cameras immediately. While describing events elsewhere he was able to keep an eye on that vital screen. Even before I switched to Kensington Palace, Richard had said ‘and as Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother arrives at the Abbey, some three or four miles away the bride leaves her home for the last time’, or words to that effect. Again, when we picked up the bridegroom’s car as it sped along the route, Richard was able to follow it continuously, even though we were only showing its progress to the viewers from time to time. Consequently, he knew its exact position whenever I decided to switch to it. This method of describing events can only be of value if many locations are involved, and where split-second switching from one to the other is necessary.

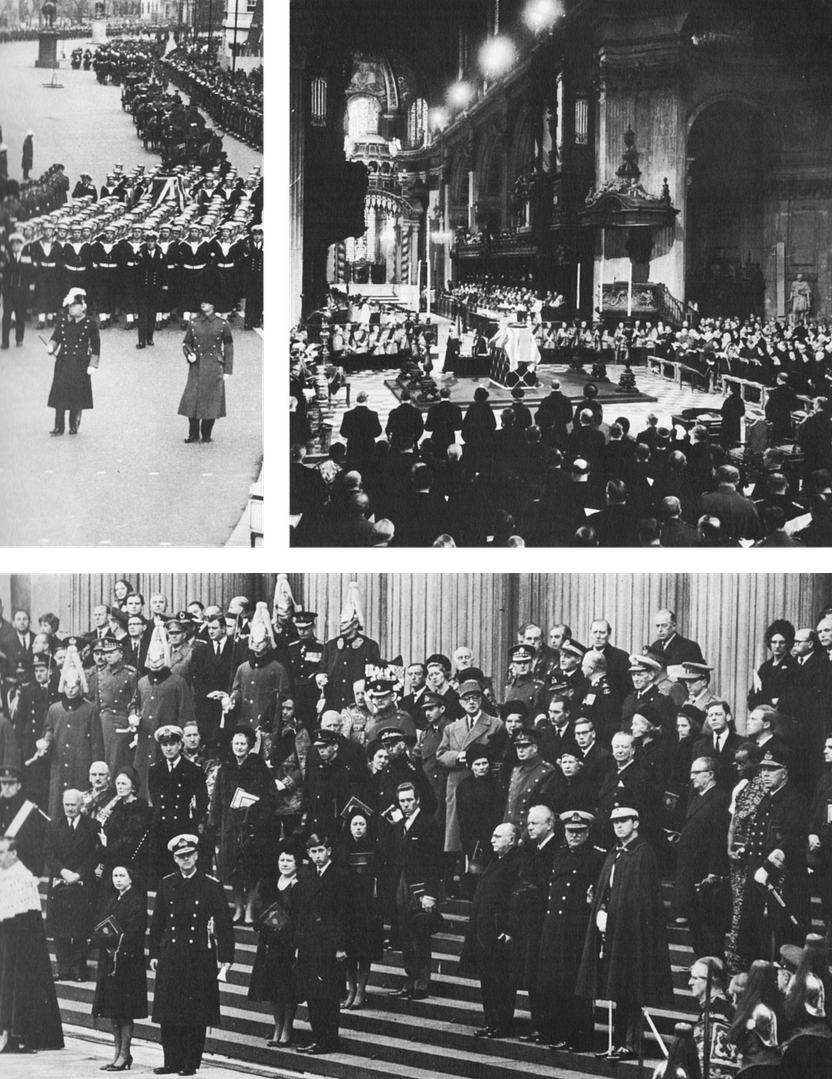

For the historic funeral of Sir Winston Churchill, Richard had two positions in the West Gallery of St Paul’s Cathedral, and our control room was in the Crypt. From one box Richard described the entire procession from Westminster to Waterloo; from the other, overlooking the Nave, he described the Service below him.

This was a mammoth effort for him. Five hours as sole commentator, then no relaxation – a hurried journey to Television Centre to edit the tapes ready for a two and a half hour transmission that night with a fresh commentary.

Few people can realise the homework Richard undertook for this epic task; the vast amount of reading necessary to assimilate every detail of the solemn events. On this broadcast he achieved a perfection he had never attained before.

As part of his preparation Dimbleby had arranged to meet the Duke of Norfolk, who as Earl Marshal was in charge of the arrangements, at 5 p.m. on the day before the funeral to settle any outstanding questions for his final commentary. The Duke of Norfolk later wrote in ‘The Times’:

‘As it happened we met at 4.15 a m. in New Palace Yard at the final rehearsal. Dimbleby asked me what I proposed to do and when I told him I was going to move up and down the route he said: “May I tag on with my car?” At about 7.30, as the morning grew lighter, he came up to me on Tower Hill and said: “Unless you want me this evening we can call off our meeting – I have all I want and you will be busy!”

It will be hard to match his gentle kindness, sense of humour, intelligence, and tact.’

The Churchill funeral broadcast will long be remembered by those who saw it and studied by generations to come. Some 600 letters came to the BBC afterwards, of which these are samples:

‘It was a triumph for everyone concerned, organisers, cameramen and commentator. I need Richard Dimbleby’s flow of language adequately to express my thanks for everything. Perhaps you would thank him, as much for his silences as for his excellent commentary.’

‘I watched from 8.30 a.m. until the end and in my humble opinion the BBC – always excellent – excelled itself! My genuine gratitude to all – no matter how humble their parts may have been – who helped to achieve such a wonderful result.’

‘I feel I must offer to you and your colleagues grateful thanks for the truly magnificent way in which you showed that epoch-making event, especially at such very short notice. The commentary of Mr Richard Dimbleby was also absolutely splendid, and fully worthy of the solemnity and splendour of the occasion, as was indeed also the carriage and behaviour of the soldiers who had the truly arduous task of carrying for long periods their precious burden. Altogether the whole proceedings were worthy of the wonderful man in whose honour they, in fact, were arranged for, and those of us who witnessed them will never forget.’