The morning was wet and the clouds so low that they almost made you crouch under them. On each side of the road there were dense pine trees with cold mist in their top branches. Eyelashes and hair were beaded with moisture, and dampness oozed into the bone. Half-past nine and the narrow road was empty – just a cleft between the pines. ‘Last time I came along this road,’ Richard said, ‘we drove like fools, because there were snipers on each side of it using the pinewoods for cover; they hung around here for quite a while. I think the turning is just a bit further on – there’s a kind of humped bridge, I think, and then we go to the left.’ The forests cleared and we turned to the left. After a few miles across the flat open heathland, we came to a small hamlet: just a few farms neatly kept, with hens and dogs and cows, children in, gumboots, and red roofs that swept down to the ground on each side of the house like the wings of an eagle. A man smoking a cigarette watched as we passed in our big car, and then, by the side of the road, the place name – Belsen.

Past the huge military camp of Hohne, then part of BAOR, once the headquarters of von Fritsch and the Panzers with an Officers’ Mess opened by Hitler; over more heathland we followed a sign to the Belsen memorial, drove through more pinewoods, and suddenly entered a car park which was empty except for some forest workmen playing football with a tennis ball in the cold rain. By the car park was the entrance to the concentration camp. It was an empty place, a cemetery in the middle of wild, silver birched and pinewooded country, the paths carefully laid out with well-brushed red gravel. Notices in different languages asked you to respect the dead lying there – about seventy thousand of them flung together in infamous anonymity. The shouts of the footballing woodmen faded as we walked across the heath to the monument. Total silence apart from the crunch of our feet on the gravel. And Richard said again: ‘Do you notice that the birds don’t sing here?’

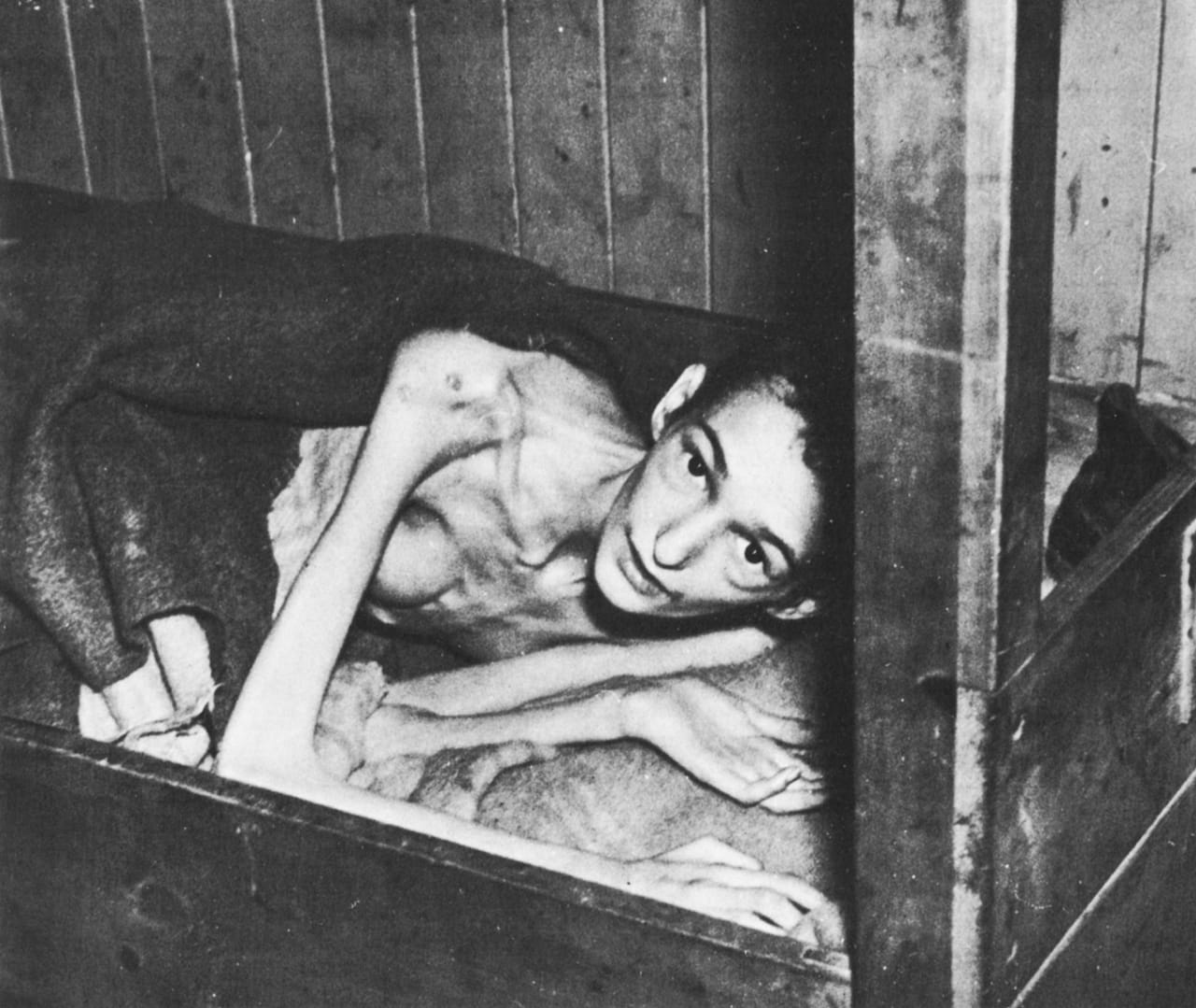

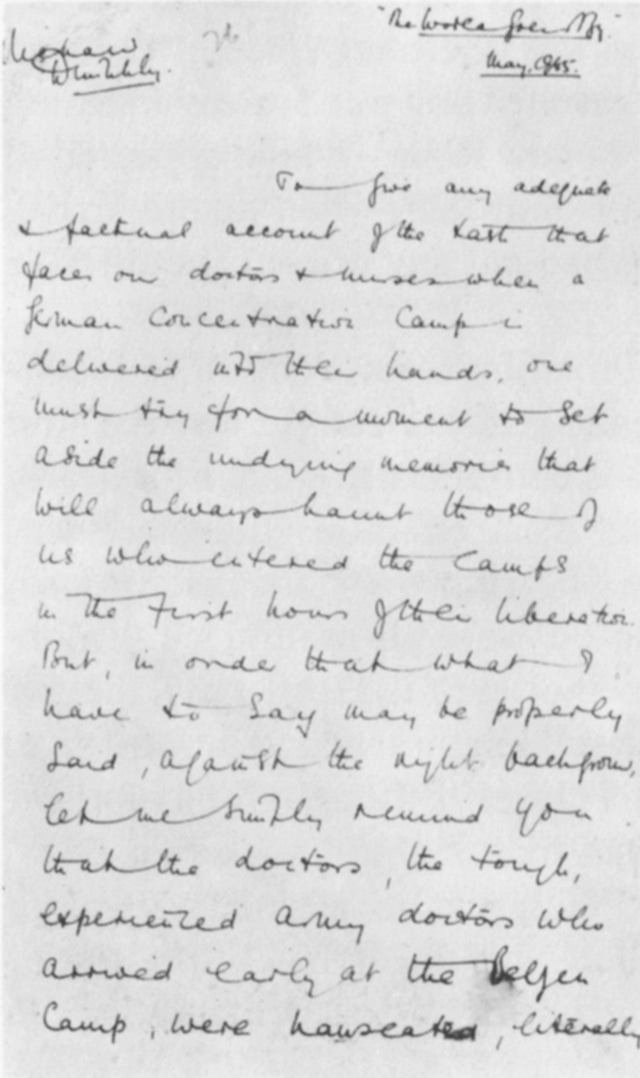

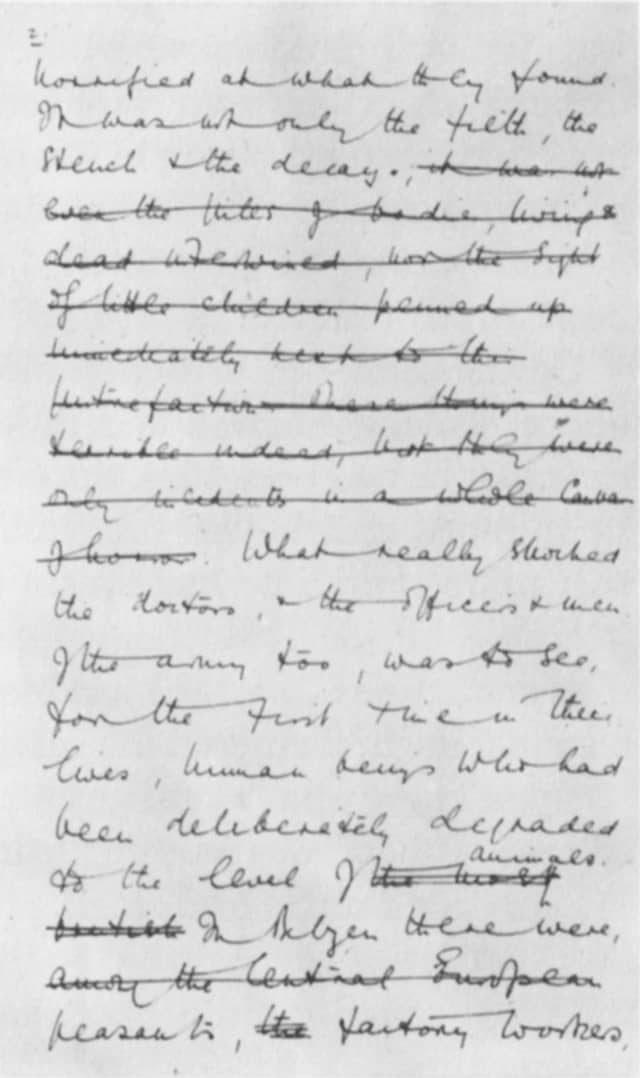

‘I came here first with one of the medical officers,’ he recalled. ‘We’d already been told as we advanced into Germany that ahead of us there was a typhoid area. I went with the officer to investigate, and we came here. It was a spring morning, warm and dusty, totally unlike today, and it was a scene of hideous filth and rubbish with a smell which had hit us long before we reached the gates – a familiar smell to us during the war which the medical officer and myself both recognised. I remember turning to him and saying, “That’s the smell of death”. But even that didn’t prepare us for what we saw. This camp was the first of these places to be opened up and the report which I sent back from here caused a lot of worry at Broadcasting House. When they heard it, some people wondered if Dimbleby had gone off his head or something. I think it was only the fact that I’d been fairly reliable up to then that they believed the story. I broke down five times while I was recording it.’

We walked past a grave marked ‘Here lie 5,000 dead’ and then further on individual graves scattered in the heather – most of them marking the memory rather than the resting place of a murdered friend, son, mother or even whole family. Some were real graves, especially down by the woods where the women’s camp used to be. But these were just marked ‘An Unknown Body’. The trees dripped with rain and it was bitterly cold. In some way they were a link. ‘I remember these trees. Emaciated people sitting among them in piles of rubbish, corpses heaped up over there, the huts down by this track, people in a state of pain, misery and hopelessness. The guards here were frightened when we took over. They expected to be shot at once, and couldn’t understand the idea of a trial. One of them asked me if anything would happen to him. I was so angry that I turned on him and told him that he would be tried and I hoped hanged.’

Suddenly a weird moment: through the trees came a heavy roar like an aeroplane flying dangerously low. It grew in intensity shattering the damp silence. Richard recognised it: ‘Tanks. That’s the very noise that the people here must have heard when we moved in to liberate them. It wasn’t a moment of joy, though, because they were scared it might be the Russians.’ The noise gradually subsided as the tanks returned to Hohne from their exercises on the heath, and time folded up for a moment as the trees were suddenly peopled with ghosts.

Richard achieved the fusing of memory and emotion perfectly by two filmed statements. Every feature which we decided to include during our walk around the camp was mentioned, all in the correct order and nothing noted on paper: ‘Earth, conceal not the blood shed on thee’ – the epitaph of Belsen on the Jewish monument, a grave to a whole family, a square of marble laid down in the heather, the unknown dead down in the woods, some with small posies of flowers on their graves, the mass burial mounds of 800, 1,000, 5,000. And all of it told in simple prose empty of adjectives. He captured the silence, the mood, his own memories with a gift of style and sympathy which was matchless. ‘When you come back after twenty years, you find the Belsen concentration camp almost, though not entirely, unrecognisable. Gone are the huts and the compounds and the barbed wire and the poor tottering people that were staggering about and the SS guards, men and women – they’ve all disappeared. The furnace where they hit them on the head and pushed them in the fire: all this has gone. And on a day like this, cold and rainy, such a contrast to the spring day on which I came here twenty years ago, there’s nothing here but the desolation of heathland. All that you really find to remind you of this place, other than perhaps the lay-out of it which I can remember as I stand here now, are graves…

We spent four hours at the camp on this wet and cold morning. We walked everywhere, down gravel paths, across soaking heather, into the woods, stumbling over decaying boots and pieces of cloth and a mildewed truncheon. Apart from these fragments, the heather and the grass had reclaimed this evil ground. By the end of the morning we were as cold as the gravestones. But never once was there any complaint, and not until we were completely satisfied with the filming did we leave.

Then we drove away through the hamlet of Belsen to a roadside restaurant, and pondered at the irony.

It was a strange communion, this return of Richard Dimbleby to Belsen. The terrors of the place lingered in the trees, the monuments to suffering and courage were in every glance. A huge wooden cross stood on the site of the ovens. Wreaths, some of them five years old, some of them new, lay beneath it. There was a prayer written on a scrap of paper by a woman prisoner in the Ravensbruck concentration camp for those who were tormenting her. When Richard read it, there seemed to be a relevance to his own condition, to the strength with which he fought his pain, and to the way in which he lived with it. ‘O Lord, remember not only the men and women of good will but also those of ill will. But do not only remember all the suffering they have inflicted on us. Remember the fruits we bought, thanks to this suffering. Our comradeship, our loyalty, our humility, our courage, our generosity, the greatness of heart which has grown out of all this, and when they come to judgment, let all the fruits that we have borne be their forgiveness.’