David Dimbleby, who had been born in 1938, was named after his godfather, David Howarth. As a fellow rebel Haworth shared the first four years of Richard Dimbleby’s broadcasting career.

Richard set about reforming the presentation of the news by starting a kind of underground movement, infecting people here and there among the staff with his own excitement at his own idea of radio news reporting. I was drawn into it early because he discovered I was prone, like himself, to wild enthusiasm, and because I was in the sound recording section, which itself was new.

We had two mobile recording units, and Richard had his eye on them from the very beginning. Now, when one can almost put a tape recorder in one’s pocket, it is odd to remember that the first of these units – they both recorded on discs – was in a converted laundry van, and the second, the perfected BBC product, filled a seven-ton truck and had a crew of four. Programme departments, at reasonable notice on the proper form, could book these outfits from us. What Richard wanted was to be able to ring up, at any time of the day or night, and rush off with one of them, then and there, wherever there was news.

The BBC was then not organised for anything so brash and spontaneous. It was nobody’s job to go with him: so it had to start in an amateurish, unofficial way. There were six or eight of us in Administration and Engineering who had the kind of temperament it needed. ‘It’s no use asking anyone, they’ll all be warm in bed. Let’s get the story and argue afterwards’ – that was his attitude, so off we went, usually after a day’s work, wherever there was a shipwreck, a flood, a story of any kind that we could conceivably reach with the laundry van or the seven-tonner.

We drove like lunatics all night, recorded his descriptions and interviews, and drove again to the nearest regional studios in time for the next night’s bulletins. I had a sports car which was vintage even then, and Richard and I often went in that, with the recording truck lumbering along as best it could: I remember tearing up the Great North Road in the middle of the night while Richard contentedly slept with his head on my lap underneath the steering wheel. And he was right: when we got the story, nobody did complain – provided we also did the full-time jobs we were being paid for.

There was one period when, for fear we missed anything, he persuaded Reuters to telephone himself or me at home, on alternate nights, if anything reportable happened. But that did not last long. Reuters night men never quite got the idea that we were tied to a lorry, and after Richard had been woken up four or five times in a night with items like a serious drought in Siberia, he let the arrangement lapse.

The cumbrousness of the lorries and their administration was his millstone. To BBC engineers quality of reproduction was all-important then; to him the only thing that mattered was to get the story and put it quickly on the air, no matter how. He and I were both convinced that a simple recording apparatus, of adequate quality, could be fitted into an ordinary car which we could drive ourselves. Or to be precise, not an ordinary car: he dreamed of something fast and showy, say a Lagonda, with an illuminated sign bbc news on the front of it, something that people would remember and expect to see. We even plotted (he loved plots) to have the recording gear made in secret and put it in the back of my car and broadcast its discs without telling anyone how we had made them; but that fell through because neither of us could afford it. It sometimes seemed hopeless to move the BBC, and at one time we tried – or plotted – to sell ourselves and our ideas to Ed Murrow of CBS, whom Richard greatly admired.

Nevertheless, by some years of lost sleep we did manage to cover a strange variety of events with those two recording trucks, and Richard’s concept of ‘our observer’ slowly began to be established. I think what might now be called the break-through for this kind of radio reporting was the night the Crystal Palace caught fire. For us there could not have been a more glorious bit of news. It started just after the final editions of the evening papers: it was exclusively our own for the rest of the night. We rushed down to Sydenham in my car, the laundry van came in behind the fire engines. Richard with his journalist’s instinct found the chief of the London Fire Brigade himself (‘David, his name’s Firebrace, life is perfect’) and he vanished into the front entrance of the blazing building. I went in at the back, just in case he never came out again.

As the time for the News came on, we found we could not possibly get away with our records again through the crowds. There was only one thing – broadcast by telephone: it had never been done before. By luck, a BBC man much senior to ourselves had turned up from somewhere. He gave the authority. Our engineers disconnected the telephone in a café (I seem to remember that they wrenched it out by its roots) and tied our recording amplifiers to it. And Richard, hopping with excitement, black and wet and minus his eyebrows, was on the air direct, with the roar of the flames, the shouting and the bells. The broadcast brought out most of the population of South London to see the fun, and that displeased the fire brigade. The quality of the telephone line displeased the BBC engineering division. But Richard was ecstatic: the event had proved his point – that if we got the story, it didn’t matter how.

By 1938 his ideas were fairly well established among listeners and in the BBC itself. We were at Heston Airport when Chamberlain landed from Munich with his piece of paper, and we recorded ‘Peace in our time’ for television as well as for radio. And immediately after we made our first foray abroad. An international force was supposed to be going to the Sudetenland to supervise its absorption into Germany, and the Germans gave us permission to go there too. So did the BBC, which surprised us even more. Neither we nor the international force ever got there – we waited in Germany for a fortnight or so – but I specially recollect that journey because the pomposity and false dignity of Nazi officials set a spark to the boyish naughtiness in Richard’s character. We were met at the frontier by a delegation in vast Mercedes cars, led by a young Aryan from the Ministry of Propaganda. I see Richard being swept into Aachen in this equipage like a visiting potentate, dispensing Nazi salutes and Heil Hitlers, and then, alighting, clicking his heels and bowing to anyone who would take notice. Who else, at that moment in history – and with his physique – would have insisted that the man from the Propaganda Ministry should teach him to goose-step?

We went first to the Hotel Dreesen in Godesberg, where Hitler had stayed to meet Chamberlain. We thought Hitler was still there, but he had gone, and all we were shown was the Fuhrer’s truckle bed, and the new green water closet Herr Dreesen had installed for him: the Fuhrer, such a simple man at heart, had been angry at the expense. Richard wrote a broadcast, tongue in cheek, about the Fuhrer’s taste in plumbing, and we went on to Hamburg. Richard naturally asked to be shown the night spots of St Pauli.

At the Zillertal guests were invited to conduct the Bavarian band. The baton was handed to Richard. They agreed to try ‘A bicycle made for two’, and the band found that Richard knew how to conduct. Then (and remember this was a time of considerable tension between Germany and Britain) Richard made the Bavarian band play ‘Tipperary’. A Norwegian from the next table came over, bowed, shook Richard’s hand, and congratulated him on his courage in calling for that tune at such a time.

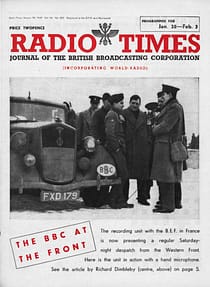

When war came, in September 1939, Richard was perfectly ready for it. He had won his way by then: we had an ordinary car, with recording gear on the back seat. A week before war was declared, he took the car to Paris, with two pots of camouflage paint, and left it there in what he thought was a bomb-proof garage. After the declaration, he and I, with Charles Gardner and an engineer named Harvey Sarney, went down Regent Street and bought ourselves uniforms at the BBC’s expense. It was both emotional and funny when we appeared in them at Broadcasting House. Uniform was still unfamiliar, and nobody could resist a laugh at Richard dressed up as a soldier; yet senior officials were dewy-eyed when they wished us God-speed. We had our picture on the cover of the Radio Times, looking (it seems to me now) absurdly young and shiny, and we quite expected to die for radio.

But when we reached France, of course, there was no war at all. The British army was starting to dig itself in on the Belgian frontier, miles from any Germans. Finding no battle there, we went right down the Maginot Line, into the wintry forests of Alsace and up the Rhine, begging the French to fire a gun so that we could record it; but they never would, in case the Germans fired one back at them. So we were driven to sending back strictly censored reports on obscure army units, broadcasting ENSA concerts, and arranging quizzes and spelling bees in which soldiers competed against their families at home.

We worked like demons at these rather uncongenial tasks. What drove us on, I think, was that we were on our own at last, with a vast field of broadcasting all to ourselves, and we were selfishly afraid that the BBC would send out a huge unwieldy staff and rob us of the shooting war when it really started. So we took on every job our head office suggested, and every one we could think of ourselves. The climax, as I remember it, was that Christmas Day when three of us – perhaps there was an extra engineer – did five major broadcasts, driving from one to the next on roads of black ice: a quiz, a church service, a piece in the traditional round-the-world programme, and two concerts, one English and one French. Nobody but Richard would have attempted anything so crazy, or been able to persuade his colleagues it was possible in one day; and I doubt if anyone else would have brought it off.

Again, it is the gaiety and the trivialities that I remember best in France, in spite of all the discomfort and the bitter cold that everyone in the Expeditionary Force remembers of that winter. There was a day in the city of Strasbourg, which had been evacuated in a panic months before. Richard had prepared a soulful piece about the deserted city, the dusty goods still displayed in the windows of the shops, the café tables still set out on the pavements, the abandoned homes. We set up our gear in a silent empty square, not a being in sight, and I gave the usual cue to Sarney: ‘We’ll start in ten seconds from now’. On the ninth second, a jaunty French soldier came marching round a corner and gave a garlicky belch which echoed round the square. The silence, the belch, and Richard’s helpless laughter were all on that record. I wonder if the Germans captured it: they got our car and all our equipment in the end.

And there were the horrors of phoney war broadcasting too, especially the quizzes, and most especially of all the one on Christmas Day. On those shows an army censor sat with us in case we revealed military secrets, of which the most carefully guarded was supposed to be the location of the British force. (Richard always longed to start ‘Well, here we are in Arras’, just to see what the censor’s orders were – to shoot him dead, or smash the microphone, or what?) We put the questions to the competitors at home in England, and the quiz-master at home put his to our team of soldiers, who that morning were in a merry and unmilitary mood. We had prepared a set of harmless questions, but we listened with horror as the alternate questions came from London. ‘What did Mary Tudor say would be found lying in her heart?’ Answer: the shockingly unmentionable name of Calais.

It went from bad to worse: I remember every mark of dismay on the censor’s face, and Richard’s lucid comments whenever our microphone was dead. And then I became aware that we had only nine competitors, instead of ten. The tenth had fallen under the table and was being sick. Instantly after that broadcast, while Richard rushed off somewhere else, I had to eject our derelict team, admit a sober congregation and introduce a church service in the same hall. It was a day of splendid confusion and delightfully near disasters, just the sort of day that Richard thrived on.

But what I remember most of all is his influence on other people, the particular kind of glow he radiated, the sense of an organism much more alive than most. Thousands of other men will remember it too from that winter in France, for by the spring there were very few army units so remote that he had not been to see them – and there was nobody in Britain, of course, who did not know his voice. I cannot describe that influence, but perhaps I can suggest it. I saw him at that period – he must have been twenty-six or twenty-seven – with every kind of person: King George VI, the C-in-C, the old French generals of Maginot Line mentality, everyone down to the dimmest of privates in the Pioneer Corps. He was always himself with them all. And I remember standing with a Brigadier, watching him interviewing some soldiers. I said something about his ability to get on with all kinds of people. ‘Of course,’ said the Brigadier, with a sudden astonishing intensity of feeling, ‘we all adore him.’ That was the secret, I think.

In France Dimbleby perfected his broadcasting technique and his French. But he chafed at the lack of military action and envied his colleague Edward Ward broadcasting from the Winter War in Finland. In April 1940 he left by flying boat for Cairo and the British Army in the Middle East.

From then on his chronicle of war despatches reads like a history of the war itself. He now saw plenty of action. He entered Bardia with the British troops and told how Italian officers and men offered to surrender to him. He went down to Khartoum, and was on his way to Abyssinia when he was struck down with diphtheria. He covered fighting in Greece and Albania, and a surrender in Syria. He lived cheek by jowl with German intelligence agents in Istanbul and was ambushed in Persia by guerillas. He travelled 100,000 miles in over a dozen countries, much of it in company with his recording engineer F. W. Chignall.

Once during the retreat back to the Alamein line their car stalled in deep sand. For twenty-four hours they had not seen another car. They took down the engine without success and Dimbleby decided one of them must start walking due north in search of a tow from some other British vehicle. He said, ‘Chig, we’ll toss up for it, and you throw the coin.’ It fell to Richard to go and many hours later he returned with a tow. Chignall recalls: ‘The real significance of this incident was that Richard, the army driver and I all knew that Tobruk had been retaken by the Germans, and that they had already put into use the transport they had captured from us. During the twenty-four hours we were broken down we were cut off from any contact with the British Army so anything Richard met could easily have been a probing force of Germans. I have always kept the coin I tossed that day.’