In June 1937 Richard Dimblehy married a girl he had met as a fellow reporter on the family newspapers at Richmond, Dilys Thomas, third daughter of a London barrister. The BBC gave him a wedding present of £5. Had he been with the staff a whole year it would have been £10. The Dimblebys were poor and happy.

Charles Gardner soon moved over from sub-editing to join Richard Dimbleby as the second BBC news observer, and between them they covered all the home news stories, while Ralph Murray continued to report the League of Nations.

Richard was fascinated by the technique of the use of recordings. He was always experimenting with sound effects and with microphone placings. Here both he and I had to observe one very clear rule of the News Talks section – there must be no faking. To fake was the unforgivable sin. The bark of the dog that roused the household against a burglar had to be the bark of the dog and not just the bark of any other dog of the same species. We were rather proud of this integrity, and when it was suggested to us, as it so often was, that rather than put all concerned to a great deal of trouble to produce some sound effect or other, we could more easily and more convincingly fake it, we used to reply with great dignity ‘News Talks never fakes’. I have some recollection of Dimbleby and Arthur Phillips spending all of some railway journey behind a new record-breaking engine recording the real sound of the train’s wheels by dangling the microphone down a lavatory pan.

About this time there was the affair of the telephone boxes. This arose after a series of headline news stories had annoyingly occurred in the remoteness of East Anglia. Probably the Fen floods was one of these stories. East Anglia was a ‘Here do dwell savages’ area on our map, because there was nowhere nearer than London we could use to play back discs for that night’s news. So, after a series of problems about getting discs back from East Anglia, and losing a high proportion of them as Railway Press Packages, Richard had his telephone box idea. What was wrong with hitching an amplifier and a BBC microphone on to a GPO box and making any telephone kiosk an impromptu Outside Broadcast point? What indeed? So Richard and, I think, David Howarth of Recorded Programmes wandered around putting in calls to Broadcasting House from telephone kiosks and getting them recorded. In the end the GPO said the whole proposal was illegal and that was that. So East Anglia remained the great broadcasting waste unless, of course, one ignored the law and used a telephone hitched up to a recording channel at Broadcasting House and then remembered to remove from the disc the ‘thrrreee minutes’ interruptions from the trunk operators (before the pips were invented). Richard did this several times for straight eyewitness pieces, and so did I. We were never prosecuted.

Richard Dimbleby in those pioneering days of BBC reporting was cheerful, good natured, intensely hard-working and bubbling with enthusiasm for each and every story. Together we made youthful common cause against the hated ‘admin’ – the administrative people in the BBC – seen by us in simple black and white terms as the ‘baddies’. ‘They’ couldn’t properly organise the instant availability of a recording car; ‘they’ would hardly sanction the spending of a halfpenny on the news service; ‘they’ challenged the need to buy a pint of beer for someone who had helped us. Fighting ‘them’ became the joy of our lives.

With hindsight and the maturity of extreme age, I can imagine that ‘they’ were really scared stiff at the possible Trojan Horse they had invited inside the walls of Broadcasting House. The BBC putting out safe bulletins ‘copyright by Reuter, Press Association, etc.’ was one thing. Any allegation of error or bias could be neatly blamed on the agencies. BBC staff reporters were different. Might they not start to editorialise – to use the great power and prestige of the BBC to shape public opinion this way or that way – even by an inflection of voice? Outside experts might just land the BBC in trouble on this score, but at least they were not BBC staff. Dimbleby and Murray and I were staff and could not be disowned or explained away.

Richard and I were then perhaps too raw, too young, or too inexperienced to give these matters of high policy a thought. We never dreamed of editorialising. We were professionally-trained reporters, interested only in conveying undisputed facts and not concerned to hold inquests. Richard spent a great deal of quiet and careful time in ascertaining, checking and cross-checking the facts. If there was a discrepancy either he left it out or used the ‘some say this – others say that’ technique without advancing his own views. But – and this is my point – we did this by instinct not by command. Of course we had views, but we never dreamt of inflicting those views on the public. Both of us had been brought up in the old-fashioned Scott school which said that facts were sacred – and the free comment was not our affair.

In the News bulletins time was strictly limited. It was common to be told ‘You have 45 seconds in the nine o’clock and you can have 2 minutes 15 seconds at ten’. Richard’s great and enduring strength, the ability to tell any story with a beginning, a middle, and an end in any stated time-scale from 30 seconds to a lavish 3½ minutes derived, I am certain, from those early days.

The News Department was impecunious – and we ourselves were perpetually broke. I remember the night in 1937 when it became clear to Richard and me that there was potentially big news in the fact that Tommy Sopwith’s America’s Cup challenger Endeavour on her return journey across the Atlantic had broken her tow and was facing full gale conditions.

We decided to cover two key places: Southampton where Sopwith’s motor yacht had now fetched up, without Endeavour hitched on behind; and Plymouth near to which Endeavour must sail if she ever regained our waters.

Richard and I tossed up for destinations. He won and chose Southampton. Then came the little matter of getting railway tickets. An office ‘float’ cash box existed for such emergencies. It was scheduled to contain £20 – the system being to extract some cash and leave a signed IOU in its place. We opened the box, and found a shower of IOUs – all of them signed by the news editor ‘R. T. Clark’. So Richard and I turned out our pockets and dunned our colleagues – but the collection fell short of £3. Our next move was to go to the Queen’s Hall opposite, where the BBC was staging the Proms. There we persuaded the cashier to give us £10 each from the till, on note of hand alone. Thus did Richard get to Southampton and I to Plymouth that night.

It was while on this story, and as a guest on Sopwith’s luxury motor yacht, that Richard, replete with champagne and feeling thirsty in the night, drank some doubtful water, contracted paratyphoid, and was seriously ill in hospital. He was away for two months. The expense involved nearly broke him and he pleaded with ‘Admin’ to get them to pay his hospital bills on the grounds that he contracted his paratyphoid on Corporation duty. The story became involved because there was a simultaneous typhoid outbreak at Croydon at the time, plus a counter allegation that Richard had been negligent in using a wrong tap to get his water. Finally the BBC split the bill down the middle, but even so Richard’s half of it was a serious problem for him. While Richard was getting paratyphoid at Southampton, I was getting seasick at Plymouth. I managed, however, via friendly pilots at the airfield, to find Endeavour and go alongside in a small hired boat to interview the Skipper – while Fleet Street was still arguing the toss in pubs ashore. I returned to start my own anti-‘Admin’ file on the matter of 3s. 6d. expended for a bottle of sea-sick remedy. We cleaned up completely in the Endeavour story for a cost of about £20. The newspapers spent hundreds – and missed out.

At this time neither Richard nor I could afford a personal motor-car. We did, however, finally set ourselves up with a jointly owned Swift purchased for £10 with capital borrowed from Ralph Murray and repaid to him out of the 3d. a mile BBC car allowance for duty journeys. Richard and Dilys had the private use of the car one weekend, and my wife Eve and I had it for the other. I have now completely forgotten what happened to the Swift, but I remember Richard coming to me very excited to say that MGs would give us a new car each (to be changed every year) if we would put ‘BBC News’ on it somewhere. Imagine the temptation – but after a mournful drink, we decided that we daren’t. My memories of Richard’s financial troubles at this time are varied, but they had one central theme, ‘Dilys has rung to say she is going to sell the piano’ – but I don’t think she ever did.

In December 1936, just before the Abdication, Richard and I were parties to one of the BBC’s best kept skeletons – the day the BBC News Department threatened to strike. The newspapers, after Bishop Blunt’s sermon, were now full of the Simpson divorce but the BBC didn’t carry a word. Eventually this became, in our view, stupid and the staff of BBC News issued an ultimatum: either that night’s bulletins made some reference to the main topic of the day – or there would be no News Bulletin at all. Richard and I weren’t directly involved, but gave our general agreement. Fortunately the matter wasn’t put to the test because that afternoon Stanley Baldwin made mention of the matter in the House of Commons and our local crisis was averted. Would there have actually been a strike of BBC News? I don’t know. The key mover, Alan Wells, who was killed by a bomb in the war, felt very strongly indeed on the subject and he had much support.

Early in 1939 the Spanish Civil War (a very difficult subject from a BBC impartiality viewpoint) was delicately covered by Richard interviewing refugees at Perpignan. Later both of us went to Yarmouth to interview all concerned in an action off the East Coast in which a Spanish warship had fired on and sunk a Spanish merchantman and alleged blockade runner. I, and half of Fleet Street, caught a train to Yarmouth. Richard said if I would get the story he would liberate the recording car and join me. I telegraphed ahead and booked the only two station taxis in the majestic name of the BBC, and thus was able to isolate Fleet Street for long enough to sign up an exclusive interview with the Spanish captain for £5. I knew that, back at the station, O’Dowd Gallagher of the Daily Express was willing to offer £100. I waited ages with my story and the interviewee for Richard to arrive with the recording car, mounting guard on the hotel stairs and concealing from our Fleet Street colleagues who had now arrived that the principal actors in the drama were upstairs in the same building. Had O’Dowd found out he would certainly have outbid me. Richard eventually showed up (the recording car had been locked up and no one had the key, so he had had to break in the garage door) and we all repaired by a back exit to the Post Office where we used our car amplifier to transmit the story and the exclusive interviews. When we finished I saw a movement behind a pillar in the GPO – it was O’Dowd, notebook in hand, taking down our stuff. His office could, of course, have got it direct in London by listening to the radio – and probably did.

We enjoyed our battles with Fleet Street. We were handicapped by having no money to bribe or buy or to hire aircraft or boats, so we used the magic of the BBC name instead. For some reason people were very willing to talk to us for nothing when they were not so forthcoming to other reporters.

I have little recollection of Richard’s coverage of the Royal Tour of Canada in 1939 save a picture of him gloomily telling me that even he who had a certain genius with BBC expense sheets was unable to account for some £96 spent on the Canadian trip and he didn’t know what was going to happen. He was very low about it for days, until suddenly he showed me a memo he’d composed which said, ‘You can’t expect me to account for every halfpenny when I am with my King’. Apparently that memo did the trick and Richard brightened up again.

Indeed, when on a job involving good hotels and a chance of a grander life than either he or I could normally afford (I think we both got under £600 a year) Richard set about making the most of it. I remember him ringing all the bells in sight in one splendid hotel and ordering a manicure, drinks in the room, and expensive sandwiches – mainly I think to enjoy seeing the shock on my face. On jobs which permitted it, the best was only just good enough for Richard, and I envied the grand manner he assumed to match his temporary opulence. I suspect that this lay at the heart of many minor clashes with the ‘Admin’. I hasten to add that these little assumptions of grandeur were done as a piece of gamesmanship against the BBC administration and always ended in a giggle of anticipation at the reception of the expense sheet.

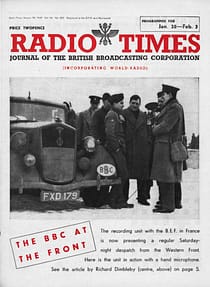

War was drawing near. Richard was to go to France with the Army and I, as a qualified pilot, with the RAF. The fun days were over; but for both of us our attitude to broadcasting, to integrity, to non-editorialisation and to careful reporting, whether we knew it or not, was shaped for all time.

If I had to name those who contributed to the shaping in those prewar days, I would say S. J. de Lotbinière of Outside Broadcasts, whose demand for professionalism and integrity extended its influence well beyond his own department, R. T. Clark with his casual but shrewd light handling of reins, Michael Balkwill for his sense of fairness and balance, and Ralph Murray’s morning criticism of what we had perpetrated the night before. But none of this would have counted if Richard himself had not been the right selection from the start. I suppose he could have set radio reporting back for five years; instead he advanced it by a decade.

I first met Richard Dimbleby in the spring of 1939. I had been brought into the BBC to run the News Talks in German, which Ralph Murray had started a month or two before. Dimbleby was about to leave for Canada and the United States to cover the tour of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. It was the first time that a Royal Tour had included a BBC correspondent.

Equipped with a new morning suit and evening tails, Dimbleby sailed on the ‘Duchess of York’ on the first of many visits to the New World. He shared a cabin with his father’s old friend Edward Gilling, for long the Court correspondent of ‘Exchange Telegraph’ who gave him many useful tips on how to deal with the elaborate retinue surrounding the Monarch.

On this journey Dimbleby substantially increased his stature as a correspondent. In addition to being a broadcaster of enterprise he became one of distinction. Handling Richard’s scripts daily, as I did at the time, one could watch his style mature and his national reputation grow during that Royal Tour. The Board of Governors recorded their appreciation of his exceptionally good work in Canada.

It was also significant that the King and Queen got to know, to like and to trust Richard Dimbleby. As they neared the American stage of their journey he posted a note (signed ‘Bumble’) from the Royal Train to his friend Muriel Howlett in News Talks.

The US looks like being pretty frantic. … We’ve also been invited to the Roosevelts’ picnic and I have fixed up to say ‘how-do’ to the gentleman himself, which will be interesting. …

I took part in an amazing broadcast at Moose Jaw the other day, for the local station, and was announced with a terrific fanfare of trumpets as the star of the evening. They brought the mike right up to the train as it arrived, and all would have been well if the bastard (beg your pardon) hadn’t got my name wrong. Very undignified having to correct him and say your name isn’t Dunglehop. I suppose he must have seen my signature somewhere.

After that he had numerous letters from Moose Jaw, one addressed to Dangleberry. ‘I think that’s the worst.’