One evening, early in May 1936, a 22-year-old journalist sat in his Bloomsbury bed-sittingroom listening to the wireless. The announcer gave the familiar introduction: ‘Here is the news, copyright by Reuter, Press Association, Exchange Telegraph and Central News.’ The news bulletin itself was authoritative, impersonal, and rather dull. It was all culled from agency messages. There were no BBC reporters, and the unseen announcer wore a dinner jacket.

The young journalist decided to write to the Chief News Editor of the BBC, John Coatman. He made detailed proposals for a livelier method of presenting BBC news and suggested a career for himself:

45 Torrington Square, W.C.1

[undated]

Dear Mr Coatman,

You may remember that a few weeks ago you were good enough to give me an interview at Broadcasting House when I enquired about possible vacancies on your staff.

Since then I have been hoping to hear from you, but I quite understand that the possible opening you mentioned may not occur for some time.

Meanwhile I am daring to make a suggestion concerning the news bulletins which you may care to consider. Naturally, I should very much like to assist with it myself, but that is not the only reason for which I make it.

It is my impression, and I find that it is shared by many others, that it would be possible to enliven the news to some extent without spoiling the authoritative tone for which it is famed. As a journalist, I think that I know something of the demand which the public makes for a ‘news angle’, and how it can be provided. I suggest that a member or members of your staff – they could be called ‘BBC reporters, or BBC correspondents’ – should be held in readiness, just as are the evening paper men, to cover unexpected news for that day. (Some suggestion of this sort is, I believe, contained in the Ullswater report.) In the event of a big fire, strikes, civil commotion, railway accidents, pit accidents, or any other of the major catastrophes in which the public, I fear, is deeply interested, a reporter could be sent out from Broadcasting House to cover the event for the bulletin.

At the scene, it would be his job, in addition to writing his own account of the event, to secure an eye-witness (the man or woman who saw it start, one of the survivors, a girl ‘rescued from the building’) to give a short eye-witness account of the part he or she played that day. In this way, I really believe that news could be presented in a gripping manner, and, at the same time, remain authentic.

Everyone, I think finds the agency reports a trifle flat after a time – as, indeed, they are bound to be. It is for that reason, I take it, that you keep an observer at Geneva, and incorporate a short talk in the bulletins on some topic of the day. But these talks are always academic – they come from an authority on the subject. There can be no vital authority on a sudden news event, unless it be the man in the street who was on the spot.

Technically, the scheme should present no difficulties. Through the Saturday Magazine and In Town Tonight, you already know that the rather uncouth voices of Londoners and countrymen can be recorded or transmitted satisfactorily, and you are used to last minute arrangements. The description of the event, in addition to the story written by the reporter and any agency matter which you may care to use, could be transmitted from the studio, to which your representative could bring the eye-witness.

Alternatively, if that person should be unable to come, it should be possible to record his or her brief description in the mobile van which you keep for actuality programmes. Such a news bulletin would itself be a type of actuality programme. I do submit, however, that a journalist should be given the job of assisting with its presentation, rather than a BBC producer.

I do not propose that the whole of the news should be treated in this way, although a staff man at the regional centres could cover you in the same way, and big events of the type could be relayed for the news from these places. The usual foreign, political, and personal news would still be supplied by the agencies or by your own representatives direct.

This principle of enlivening news by the infusion of the human element is being followed in other spheres, as you know. The newspapers, of course, have demanded interviews for their big stories for many years, and I myself have had to obtain eye-witness accounts and personal interviews for hundreds of stories of all types.

The newsreels are following suit, The March of Time being an example. In this, as you may have seen, the method followed is that of not only showing the news, but telling why, and how, it happened. That is what I suggest the BBC could do with great success, not only with sudden events or catastrophes, but with all types of news which at present come to the listener from the pen of a Press Association or Exchange Telegraph man who gives the same story to hundreds of provincial evening papers and London dailies.

If the news service of the Corporation is to be extended, both for home programmes and those to the Empire, would this not be a valuable part of the programme? It does seem to me that in the future and particularly in the event of national emergency, the BBC will play a vital part. Recorded news bulletins of the type I suggest would also prove valuable libraries of this century, for the next.

If you put this scheme into operation, or even included part of it in your future scheme, I should be happy if I were able to play a part.

I have had the type of experience needed, both among country people in the provinces and in the suburbs. Now I am in Fleet Street, and it may possibly interest you to know that I have been appointed news editor of the Advertiser’s Weekly – I now have, I believe, the doubtful honour of being Fleet Street’s youngest editor, a position which my father enjoyed thirty-five years ago at the same age.

But I have detained you far too long already. I hope that you have found time to read this long letter, and that it may be of some use. I do hope that there may be some opportunity for me in your department in the not too distant future, for I really am interested and confident that I should be of use to you.

Yours very truly,

Richard Dimbleby

The BBC News Department happened to have a vacancy for a subeditor at the time and Dimbleby was urged to apply formally for that post. In May 1936 he was not quite twenty-three, but had been working in printing and newspapers for nearly five years.

‘… I am a member of an old journalistic family – my father has been in Fleet Street and Whitehall for nearly forty years – and I have had hard experience in many branches of daily and weekly newspaper work.

‘After preparatory education at “Glengorse”, Eastbourne, I went to Mill Hill School. I was afterwards prevented from going to University, but obtained London University matriculation. Almost immediately after leaving school, I went into my family’s newspaper and printing business at Richmond, Surrey, started at the bottom, and worked my way through printing, paper, and advertising departments before joining the reporting and sub-editorial staffs of the three weekly papers.

‘I remained at Richmond, carrying out all types of local news work and sub-editing until the Spring of 1934, when I joined the staff of Southern Newspapers, Ltd, Southampton. Here I was on the editorial staffs of the Southern Echo and Bournemouth Daily Echo, and was local correspondent in the New Forest area for the leading London dailies and news agencies. I represented both of these evening papers at the same time over an area of a hundred square miles, sending each separate stories of all news events, principally from the New Forest area. As a district representative and during Head Office work, I carried out a great deal of sub-editing as well as general and descriptive reporting. I became used to all forms of rapid news work, at any hour of the day or night.

‘In December last year, I resigned and joined the staff of the Advertiser’s Weekly, Fleet Street, for the sake of coming back to London. After working for three months on the editorial staff, I have been appointed News Editor; and rank, I believe, as the youngest news editor in Fleet Street. Naturally, I am having hard experience here, as this paper has a reputation for weekly exclusive stories, and is regarded as one of the boldest and most go-ahead trade or news papers in the country.

‘I write shorthand, have a fairly fluent command of French and a smattering of German. I also have a car, and live alone within a mile of Broadcasting House. I am single….’

References were taken up. Dimbleby’s former Headmaster at Mill Hill, the great M. L. Jacks, wrote:

‘I knew him well when he was a boy at this school a few years ago, and I formed a high opinion of his character and ability. His conduct, industry, and progress were always good, and he did well all round. He had the faculty of getting on with other people, and was universally liked. I have no hesitation in recommending him for an appointment on your staff; you would, I am sure, find him trustworthy, reliable, and always anxious to do his best; I think his best will be very good.’

In the event, Charles Gardner, rather than Dimbleby, was appointed to the sub-editor post, but soon there was a more suitable vacancy and Dimbleby was engaged to start work as a Topical Talks Assistant in the News Department on Monday 14 September 1936. Ralph Murray, his immediate boss, was however due to leave on 16 September for Geneva to report from the League of Nations. Dimbleby arranged with Murray to arrive on Friday 11 September and work over the weekend to familiarise himself with the new job.

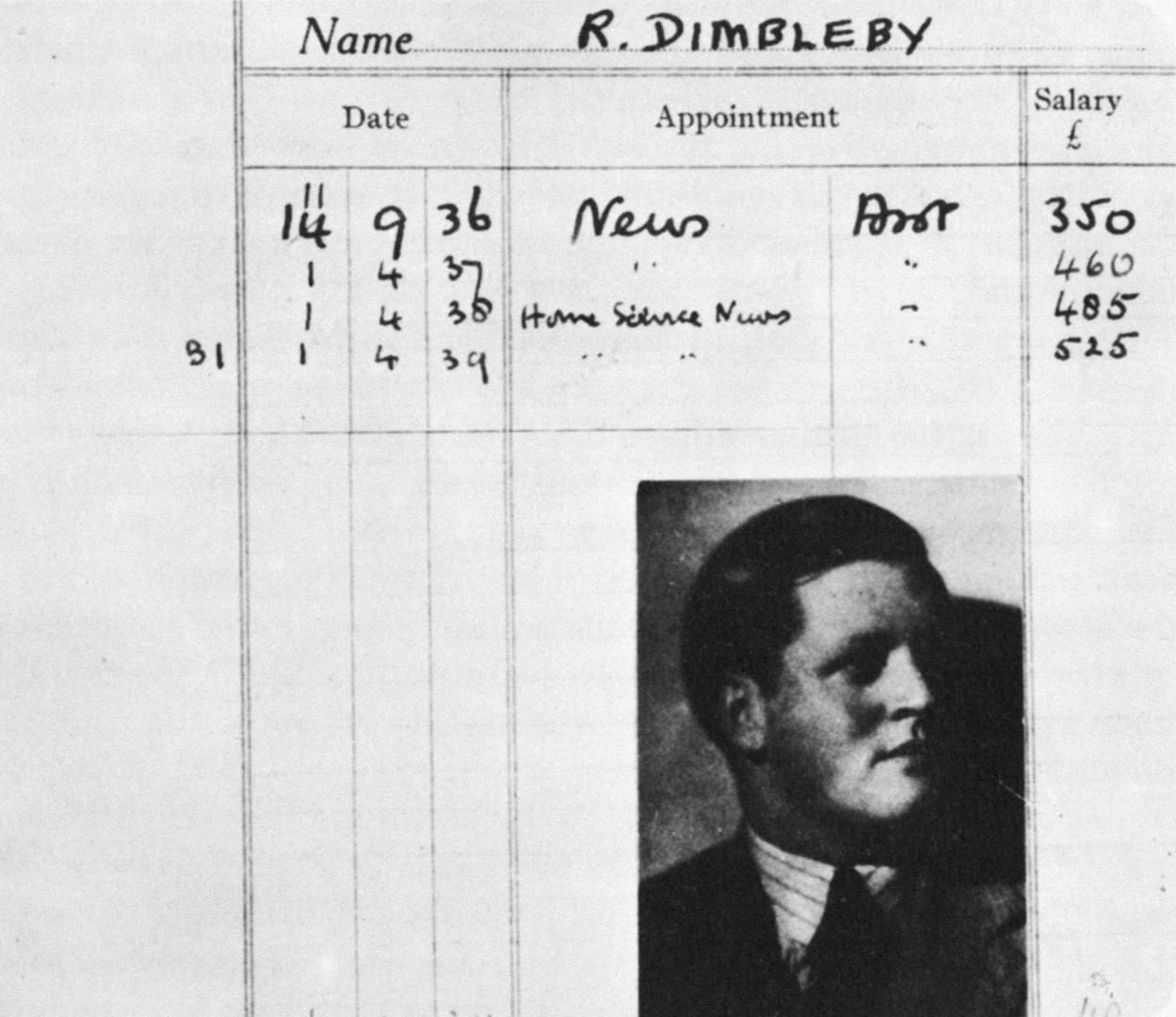

It was typical of Dimbleby to arrive early and do the maximum preparation. In the Staff Record ledger kept by Sir John Reith in the Director-General’s office his starting date had to be adjusted. His salary was £350 a year.

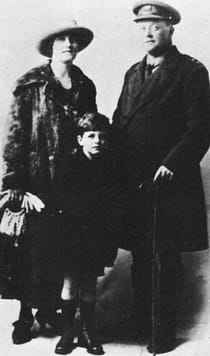

Frederick Richard Dimbleby was born on 23 May 1913 into a journalistic family. His grandfather, F. W. Dimbleby, had acquired a group of local newspapers at Richmond, Surrey, towards the end of the last century. His father, Frederick J. G. Dimbleby, had worked in Fleet Street for much of his life. He had served Lloyd George, and had been press officer at the Ministry of Labour. For many years he was the political correspondent of the ‘Daily Mail’, but he fell out with his employers over pre-war attitudes to fascism and withdrew to the less lucrative field of the family local papers.

This change in the Dimbleby fortunes put an end to Richard’s hopes of going on from his public school to Oxford or Edinburgh and eventually becoming a surgeon. Instead he put on an apron and was set to work at F. W. Dimbleby and Sons Ltd to learn all about printing and the newspaper business. He was taught to set type and to write copy. He covered police court cases and organised advertising.

His mother, née Gwendoline Bolwell, had a pleasant contralto voice. She used to sing to young Richard and his sister Patricia. She also used to sing for the Richmond Operatic Society, in musicals such as ‘Rose Marie’, ‘The Desert Song’ and ‘The Vagabond King’. Indeed the Dimbleby background held elements of show business as well as journalism. Richard’s father was on the business-management side of the Richmond Operatic Society, and Richard himself loved the weeks when at the age of twelve he acted as call boy. At Mill Hill he played Ralph Rackstraw in the school production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s ‘H.M.S. Pinafore’, and throughout his broadcasting career he relished being produced as an actor enjoys good direction.

Richard Dimbleby was also a talented pianist and organist. Later, on countless occasions in all parts of the world he was to entertain friends with improvisations at the piano. He was the first to play publicly on the new organ at the Festival Hall, and once the London air rang out with ‘Oranges and Lemons’ when Richard played the bells at All Hallows Church at the Tower. Music and messing about in boats were always his main sources of relaxation.

By twenty-three he had had a thorough grounding in journalism, and plenty of energy, enthusiasm and self-confidence. But he had no experience at all of broadcasting.

L. F. Lewis, now the Engineer in charge of Sound Outside Broadcasts, was told to take the BBC’s only mobile recording van to the model engineering exhibition at the Royal Horticultural Hall in London, and look out for a rosy-faced young man outside the entrance. ‘For goodness sake help me,’ Richard said. ‘This is my very first BBC job.’ Twenty-four hours later he told Lewis, ‘It’s all right, I’m in.’ He was, but only just.

Tony Wigan, BBC United Nations Correspondent, was then chief sub-editor. He recalls:

‘He very nearly didn’t make it. His very first broadcast in the nine-thirty News was heard by the Director-General, then Sir John Reith, to us both a deeply respected and rather frightening man. The Newsroom phone rang three times, the signal that the D.G. was on the line. He enquired the name of the reporter in the News and on being told said only that he never wanted to hear him again. But Dimbleby was given another chance and matters arranged themselves.’

Arthur Phillips, a Programme Assistant with the mobile recording van, went with him on his first actuality news broadcast which came from a cowshed near Amesbury, hardly an auspicious beginning for a great broadcasting career.

‘Cherry, a champion cow, had broken the milking record and Richard Dimbleby was sent down to cover this great event. We went down together with the recording van and by the light of a hurricane lamp – and with Cherry breathing steamily over his shoulder – Richard made his first radio interview. He put up the microphone and said “Moo” – and she mooed. But this was only half the job; the recordings which were required for the ten o’clock News had to be edited and transmitted from the Bournemouth studio, a very primitive lash-up of a place over a cycle shop. Just before transmission the only gramophone turntable in the place completely gave up the ghost and nothing would make it rotate.

‘Writing of this some years later, Richard said, “As the ten o’clock News approached I was in despair. To tell the truth, I had an unpleasant feeling that if my first effort at broadcasting was a failure I might lose my nerve and never be able to do the job at all.” But his anxiety was never apparent to me as I turned the record with my finger for the duration of the broadcast. As he said later, “The whole thing went off like a dream, and no one in the world was happier than I, though the memory of it made me tremble.”

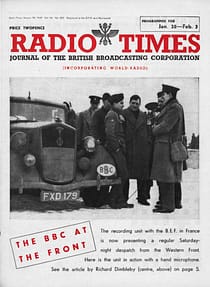

‘He tackled his news reporting with zest and tireless enthusiasm; floods in the fens, gales on the Welsh coast, an interview with William Morris, the motor magnate, a shipwreck, a stranded Cornish lighthouse keeper, were some of his early assignments, and recording engineers L. F. Lewis, Harvey Sarney and myself spent many hours in his ancient Morris Oxford being driven at breakneck speed about the countryside. We were always reluctant to sit in the front seat with Richard, for when it got dark and the engine warmed up you could see the exhaust manifold glowing white hot through a hole in the floorboards, and when you complained the answer you got was – “Nothing to be afraid of, it’s done thousands of miles like that”. It had, too.

‘Dimbleby was not yet a household word. There were inevitably times when it was either mispronounced or misspelled. Before the war he was to report on some fleet exercises off Gibraltar, and in the harbour a destroyer steamed alongside the P & O liner that had taken him out from England and a voice called over the loud hailer, “Have you a Mr Soapleby aboard?” He was Mr Soapleby for the rest of the exercise, preferring the Ward Room’s mild amusement at this rather odd name to the mirth he thought there would have been had he told them of their mistake.’