From then on Dimbleby had all the activity, and the danger, that he sought. He was constantly risking his life flying deep into enemy country. He flew in the first 1,000 bomber raid. He took part in the first air raid on Berlin. A German flakburst, only six feet away, almost turned the Lancaster over. The pilot did something violent to the stick and the bomber recovered itself. Dimbleby, who was prone to airsickness, was overcome. He pushed off his flying mask and vomited on the floor. The bomber eventually got back safely to its base somewhere in England, and Dimbleby pushed his way into the night express for London and the studio to broadcast his eyewitness account.

One seat was left. Swinging his bag onto the rack he dropped into it. As the train gathered speed two soldiers looked in, and finding the compartment full, stood in the corridor outside. Dimbleby was the only civilian other than an elderly woman opposite. She looked at the soldiers standing in the corridor, back at Dimbleby, and said, ‘I should have thought a lucky young man like you would have given up his seat’. Richard was too tired to reply.

That incident and many others in his exciting and dangerous life as a war correspondent are to be found in his book ‘The Waiting Year’ in which he rather curiously called himself ‘John Mitchell’.

The following despatches give something of the flavour of his wartime broadcasts after D-Day.

NORMANDY BEACHHEAD

11 June 1944. I saw the shining, blue sea. Not an empty sea, but a sea crowded, infested with craft of every kind: little ships, fast and impatient, scurrying like water-beetles to and fro, and leaving a glistening wake behind them; bigger ships in stately, slow procession with the sweepers in front and the escort vessels on the flank – it was a brave, oh, an inspiring sight. We are supplying the beaches all right – no doubt of that. We flew on south-west, and I could see France and Britain, and I realised how very near to you all at home in England is this great battle in Normandy. It’s a stone’s throw across the gleaming water.

I saw it all as a mighty panorama, clear and etched in its detail. There were the supply ships, the destroyers, the torpedo boats, the assault craft, leaving England. Half way over was another flotilla, and near it a huge, rounded, ugly, capital ship, broadside on to France. There in the distance was the Cherbourg peninsula, Cherbourg itself revealed in the sun. And there, right ahead now, as we reset course, were the beaches. Dozens, scores, hundreds of craft lying close inshore, pontoons and jetties being lined up to make a new harbour where, six days ago, there was an empty stretch of shore.

BOMBING OF DUISBURG

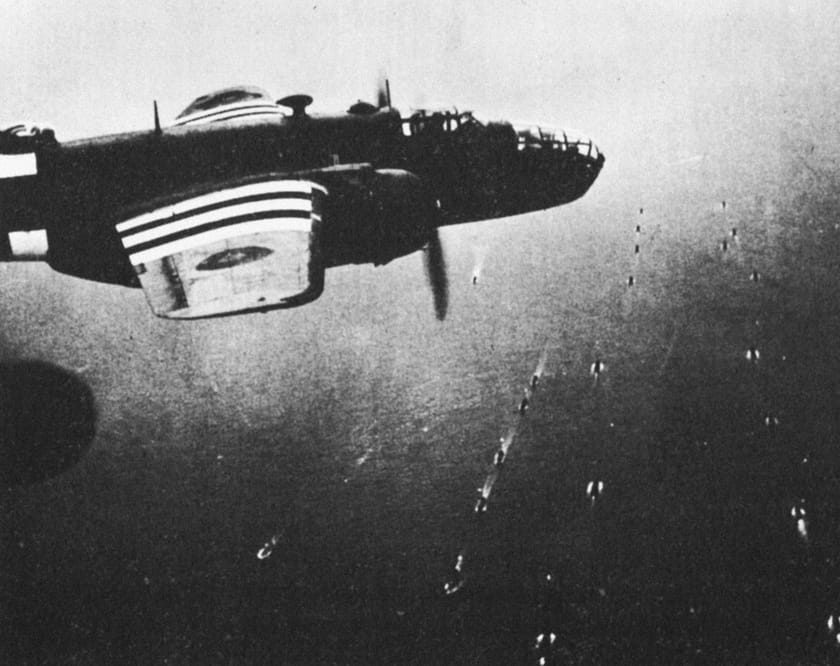

14 October 1944. I think that not only in the smoke and rubble of Duisburg, but deeper in the heart of Germany, there must be men charged with the defence of the Reich whose hearts tonight are filled with dread and despair. For the unbelievable thing has come to pass – the RAF has delivered its greatest single attack against a German industrial target since the start of the war – more than a thousand heavy bombers, more than 4,500 tons of bombs – and it did it, this morning, in broad daylight.

At a quarter to nine this morning I was over the Rhine and Duisburg in a Lancaster, one of the thousand and more four-engined machines that filled the sunny sky to the north and south-east. A year ago it would have been near suicide to appear over the Ruhr in daylight – a trip by night was something to remember uncomfortably for a long time. Today, as the great broad stream of Lancasters and Halifaxes crossed the frontier of Germany, there was not an aircraft of the Luftwaffe to be seen in the sky, only the twisting and criss-crossing vapour trails of our own Spitfires and Mustangs protecting us far above and on the flanks.

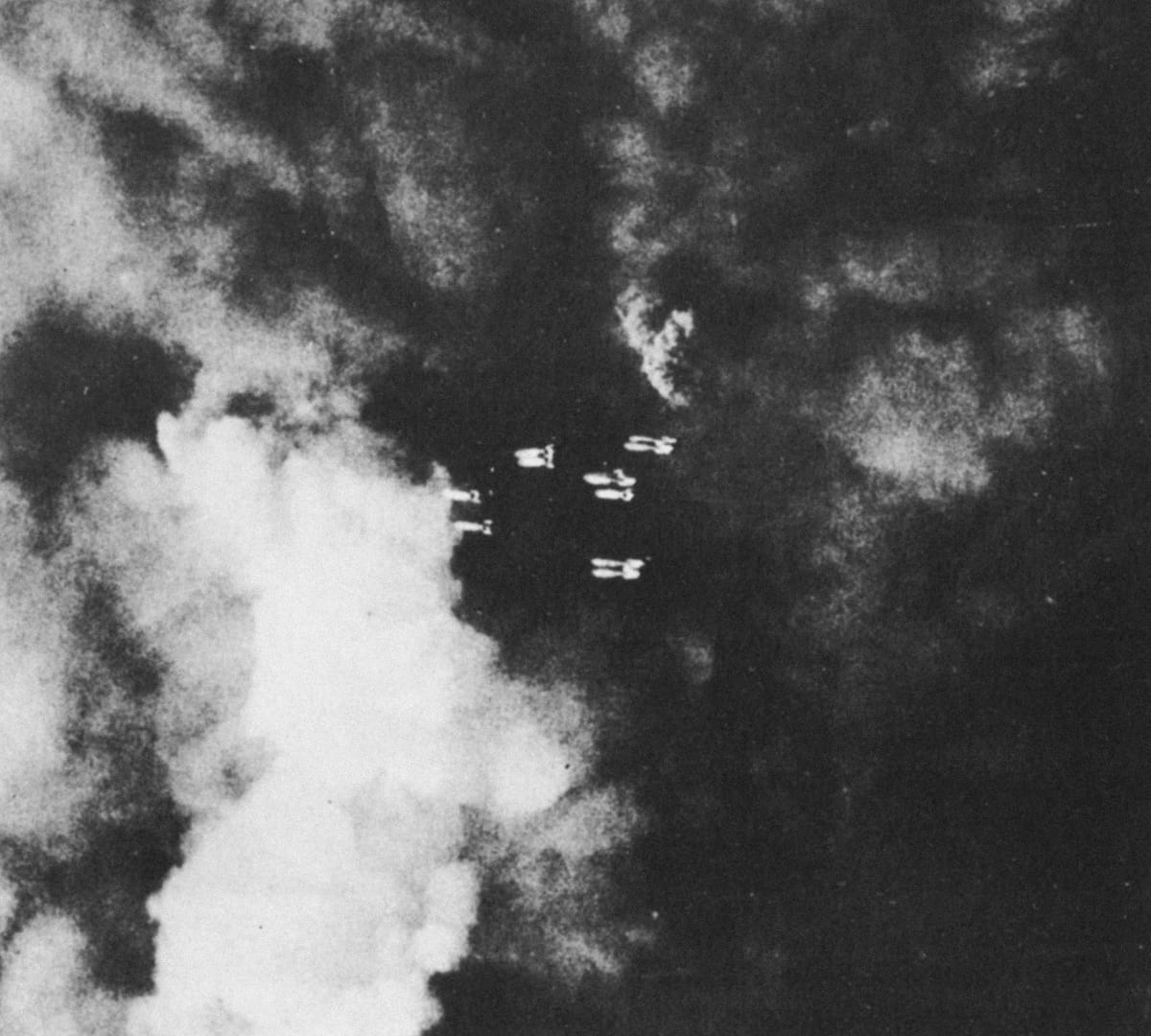

The briefing officer had described Duisburg as the largest inland port in the world and an arsenal of the Reich, when he addressed the air crews. I saw Duisburg the arsenal, just for a moment, in a hole in the patchy white clouds that lay over the Rhine and the Ruhr. I saw the grey patch-work of houses and factories, roads, railways, and the dirty dark waters of the great river curving its way through the inland port. Then target indicators and bombs, H.E. and incendiary, nearly 5,000 tons of them, went shooting down; and the German flak, and a good deal of it, came shooting up. Duisburg the arsenal disappeared under a filthy billowing brown bulge of smoke. I saw no fires from our Lancaster – there was too much cloud for that – and I had one nervous eye on the chessboard of black bursting shells that had been superimposed on our fine clear piece of sky. But I did see heavy bombs, cookies, going down into the brown smoke, and more clouds of it pushing their sullen way up from the ground. Duisburg lay underneath the shroud; and shroud, I think, is the right word.

In case it sounds rather easy, this smashing of German targets by day, let me say at once that the pilots who are going to do it from now on are taking very great risks each time they set out on such an operation. The best they can hope for is a thick curtain of bursting shells through which to fly, and the sight – the sight that we had this morning – of one or two of their companions twisting down to the ground in flames and smoke. But such hazards do not affect the plans of Bomber Command, that astonishingly versatile organisation that began the war with so little, and by courage and perseverance has built up today’s striking force. As we flew home this morning, and saw a tight orderly patch of Flying Fortresses engaged on their Cologne operation passing us above the clouds, I could not help but realise that, together, Britain and America can now put into the morning or afternoon sky a mighty force of bombers that spells destruction and ruin for our enemies.

PATHFINDERS OVER COLOGNE

1 November 1944. Last night I flew for the first time with the Pathfinders, the force whose job it is to ensure the accuracy and concentration of the attack by marking the exact aiming point with coloured indicators – red, green, and yellow flares. The main force of bombers aims at the centre of the cluster of flares and thus gets its whole load of bombs into the exact ground area chosen as the target. This job of pathfinding, which is done by picked crews, demands a particular skill in navigation and, perhaps, a very high degree of determination, for the Pathfinder cannot let himself be deflected from his precise course as he approaches the target.

Last night our job was to replenish the flares already dropped by the Pathfinders ahead. The first cluster went down as we were approaching, red and green lights hanging from their parachutes, just on top of the great white cloudbank that hid Cologne. This was ‘sky-marking’: the bombs of the main force, now streaming in above and below us, jet black in the brilliant light of the full moon, had to pass down by the flares. They vanished into the cloud, and soon the underside of it was lit by a suffused white glow, the light of incendiaries burning on the ground and the baffled searchlights. The flares seemed to be motionless, but round them and just under as we drove steadily over in a dead level straight line, the German flak was winking and flashing. Once a great gush of flame and smoke showed the bursting of a ‘scarecrow’, the oddity designed by the Germans to simulate a heavy bomber being shot down, and so to put any of our less experienced pilots off their stroke. There were fighters around too. A minute or two before we had seen the yellow glow of one of the new jet-propelled variety climbing at a great speed above us and to starboard.

We circled round the flares, watching the light under the cloud going pink with the reflection of fire and, silhouetted against it, the Lancasters and Halifaxes making off in the all-revealing light of the moon. Then we, too, turned for home.

Dimbleby was proud that his account of the crossing of the Rhine was subsequently chosen for inclusion in ‘The Oxford Book of English Talk’.

OVER THE RHINE

25 March 1945. The Rhine lies left and right across our path below us, shining in the sunlight – wide and with sweeping curves; and the whole of this mighty airborne army is now crossing and filling the whole sky. We haven’t come as far as this without some loss; on our right-hand side a Dakota has just gone down in flames. We watched it go to the ground, and I’ve just seen the parachutes of it blossoming and floating down towards the river. Above us and below us, collecting close round us now, are the tugs as they take their gliders in. Down there is the smoke of battle. There is the smoke-screen laid by the army lying right across the far bank of the river; dense clouds of brown and grey smoke coming up.

And now our skipper’s talking to the glider pilot and warning him that we’re nearly there, preparing to cast him off. Ahead of us, another pillar of black smoke marks the spot where an aircraft has gone down, and – yet another one; it’s a Stirling – a British Stirling; it’s going down with flames coming out from under its belly – four parachutes are coming out – one, two, three, four – four parachutes have come out of the Stirling; it goes on its way to the ground. We haven’t got time to watch it further because we’re coming up now to the exact chosen landing-ground where our airborne forces have to be put down; and no matter what the opposition may be, we have got to keep straight on, dead on the exact position. There’s only a minute or two to go; we cross the Rhine – we’re on the east bank of the river. We’re passing now over the army smoke-cloud.

Stand by and I’ll tell you when to jump off.

The pilot is calling up the – warning us – in just one moment we shall have let go. All over the sky ahead of us – here comes the voice – Now! – The glider has gone: we’ve cast off our glider.

We’ve let her go. There she goes down behind us. We’ve turned hard away, hard away in a tight circle to port to get out of this area. I’m sorry if I’m shouting – this is a very tremendous sight!

THE GERMAN PEOPLE

8 April 1945. We had come into the German kitchen not to fraternise, that strictly forbidden practice, but because we had seen a large radio set there and wanted to hear the BBC news at nine o’clock. It took us some time to find London on the dial and the announcer had already begun the bulletin when we brought his voice, loud and clear, into the room.

The hotel family was already there when we came in. The old, white-haired man who watched us fearfully – I think the Germans had told him terrible stories of what we would do – his two not unattractive daughters, by no means frightened, and his grey-haired wife who sat knitting at the table. A woman friend was visiting them – one of the smarter women of the little town, with her hair caught up in a bright turban and wearing what looked to me like fully-fashioned silk stockings. They – at least, the women – were ready and anxious to talk, but we made it pretty clear that we had come in only to hear the wireless.

As we sat listening to the news about this battle area, I watched the reaction of this German family which had been engulfed in the fighting a very short time before, and could hear it going on now if we’d turned off the set. They were listening quite intently, understanding no English but catching the German place-names as Freddie Grisewood mentioned them. ‘Hanover,’ said the smart guest, ‘they’re near Hanover.’ ‘Isn’t that what he said?’ she asked me. I said it was. And then the Weser was mentioned and that being the local river, everyone heard it. Even the old man stirred himself from his gloomy apprehension. And then it was announced that the Americans were at or near Wurzburg. ‘Wurzburg? Where’s Wurzburg?’ asked one of the daughters. The other got up and fetched a gazetteer from a shelf. She opened it at the map of Central and Southern Germany and the whole family pored over it, marked the places as they were mentioned.

And as I watched them, a thought struck me. This was a recital from London of our success, of the growing and spreading defeat of their country, and yet there was not one sound or sign of regret on their faces, no shock, no despair, no alarm. They just picked up what was said, checked it on the map and noted it just as if they were a bunch of neutrals hearing all about somebody else. And indeed, I believe that that’s what many of these front-line German people are: neutrals in their own country. They seem to have lost the power of passion or sorrow. They show no sympathy for their army, for their government, or for their country. To them the war is something too huge and too catastrophic to understand. Their world is bounded by the difficulties of managing a country hotel – and there’s no room in it for things outside.