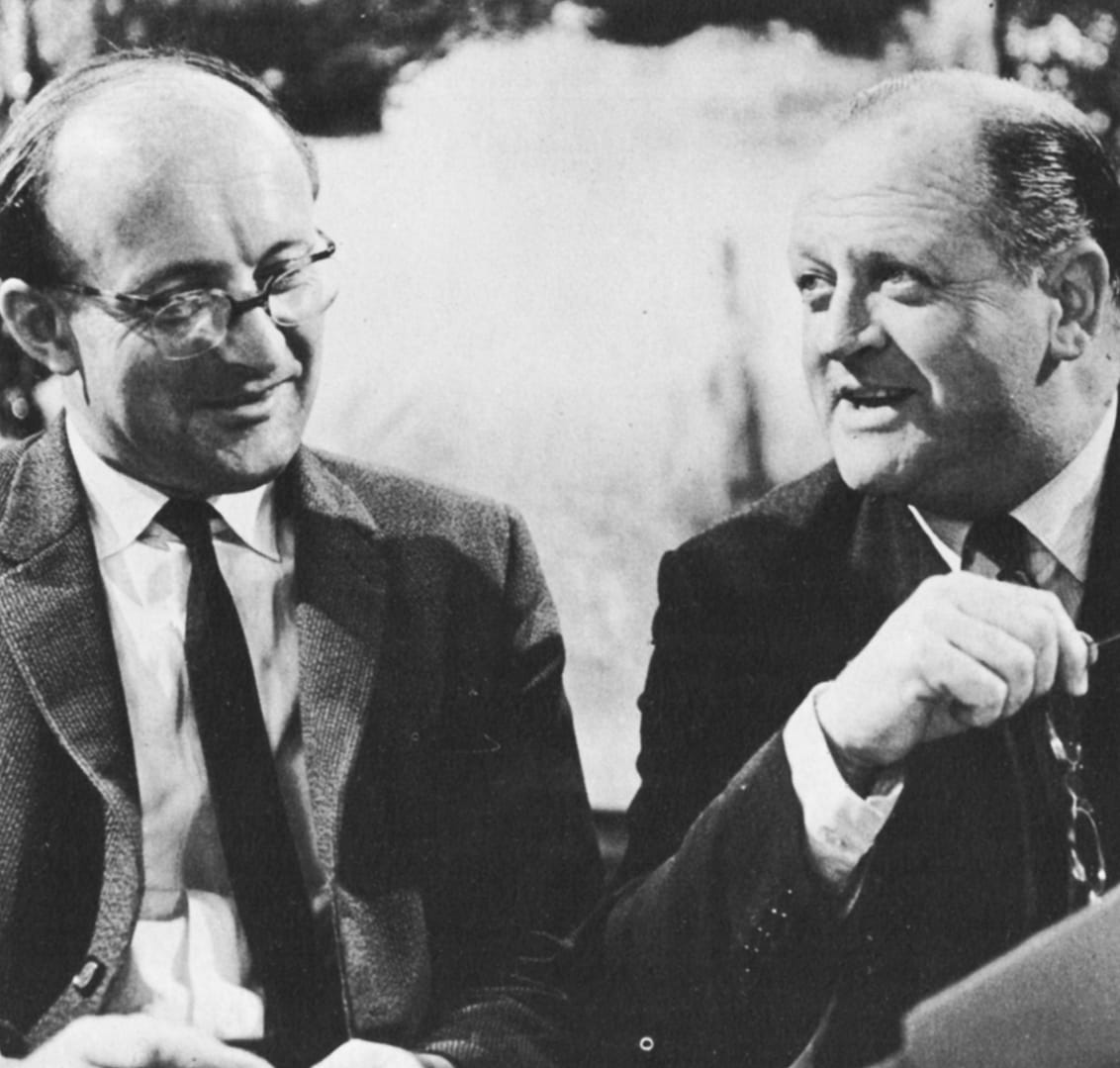

When Richard Cawston came to join the production team of Panorama from Film Department he brought with him a scheme which had long been cherished by Charles de Jaeger, a cameraman with a Viennese background. De Jaeger, who seemed to have relations in every capital of Europe, as well as an outsize sense of humour, wanted to make a visual April Fool’s joke about a spaghetti harvest.  The proposal never got anywhere until Cawston arrived at Panorama and then it had to wait until 1 April came on a Monday. In 1957 it did. Charles de Jaeger was on another assignment in Switzerland near Lugano. He stuck twenty pounds of spaghetti on to laurel bushes with sellotape and photographed it from every angle. All of us involved with Panorama, and Richard himself, felt it was high time that television was taken with some critical scepticism. David Wheeler wrote a script and Richard put it over dead pan. As the film opened with shots of burgeoning buds, Richard said:

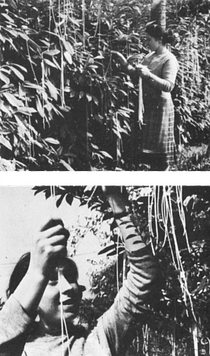

The proposal never got anywhere until Cawston arrived at Panorama and then it had to wait until 1 April came on a Monday. In 1957 it did. Charles de Jaeger was on another assignment in Switzerland near Lugano. He stuck twenty pounds of spaghetti on to laurel bushes with sellotape and photographed it from every angle. All of us involved with Panorama, and Richard himself, felt it was high time that television was taken with some critical scepticism. David Wheeler wrote a script and Richard put it over dead pan. As the film opened with shots of burgeoning buds, Richard said:

It isn’t only in Britain that spring this year has taken everyone by surprise. Here, in the Ticino, on the borders of Switzerland and Italy, the slopes overlooking Lake Lugano have already burst into flower, at least a fortnight earlier than usual. But what – you may ask – has the early and welcome arrival of bees and blossoms to do with food?  Well, it’s simply that the past winter, one of the mildest in living memory, has had its effect in other ways as well. Most important of all, it’s resulted in an exceptionally heavy spaghetti crop. The last two weeks of March are an anxious time for the spaghetti farmer. There’s always the chance of a late frost which – while not entirely ruining the crop, generally impairs the flavour, and makes it difficult for him to obtain top prices in world markets. But now these dangers are over, and the spaghetti harvest goes forward.

Well, it’s simply that the past winter, one of the mildest in living memory, has had its effect in other ways as well. Most important of all, it’s resulted in an exceptionally heavy spaghetti crop. The last two weeks of March are an anxious time for the spaghetti farmer. There’s always the chance of a late frost which – while not entirely ruining the crop, generally impairs the flavour, and makes it difficult for him to obtain top prices in world markets. But now these dangers are over, and the spaghetti harvest goes forward.

Spaghetti cultivation here in Switzerland is not, of course, carried out on anything like the tremendous scale of the Italian industry. Many of you, I’m sure, will have seen pictures of the vast spaghetti plantations in the Po Valley. For the Swiss, however, it tends to be more of a family affair. Another reason why this may be a bumper year lies in the virtual disappearance of the spaghetti weevil, the tiny creature whose depredations have caused much concern in the past.

After picking, the spaghetti is laid out to dry in the warm Alpine sun. Many people are often puzzled by the fact that spaghetti is produced at such uniform lengths, but this is the result of many years of patient endeavour by plant breeders who have succeeded in producing the perfect spaghetti. And now the harvest is marked by a traditional meal. Toasts to the new crop are drunk in these poccalinos, and then the waiters enter bearing the ceremonial dish, and it is, of course, spaghetti, picked earlier in the day, dried in the sun and so brought fresh from garden to table at the very peak of condition. For those who love this dish there’s nothing like real home-grown spaghetti.

The film ended with Swiss in national costume tucking into the meal and we came back to a shot of Richard at his Panorama desk closing the programme.

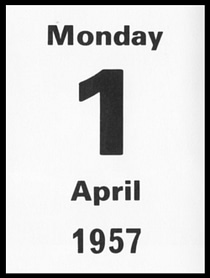

We had arranged for an outsize calendar to be on his desk proclaiming 1 April and Richard said: ‘and that is all from Panorama on this first day of April’. Nevertheless, a very large number of people were hoaxed. I went to the BBC’s telephone exchange in Lime Grove where for the next two hours calls came in incessantly. Some were from viewers who had enjoyed the joke, including one from Bristol who complained ‘spaghetti doesn’t grow vertically, it grows horizontally’. But mainly they came with the request that the BBC should settle a family argument. The husband knew it must be true that spaghetti grew on a bush because Dimbleby had said it. The wife knew that spaghetti was made with flour and water. Neither could convince the other.

I had thought it wise to inform the Director-General of the BBC, Sir Ian Jacob, beforehand that this hoax was due to be perpetrated in a current affairs programme. Unfortunately, someone forgot to pass my message on. I ran into Sir Ian two days later at Broadcasting House. He said: ‘I always used to think that monkey nuts grew on bushes until I went to serve in the Canal Zone and saw them growing on the ground. The moment I saw the spaghetti item on Panorama, I said to my wife, “I’m sure spaghetti doesn’t grow on a bush.” We had to look up three books before we confirmed it.’