Charles Collingwood, now Chief European Correspondent of the Columbia Broadcasting System, was a fellow war correspondent with Richard Dimbleby throughout World War II. He knows at first hand the problems of the television performer.

I remember running into Richard Dimbleby at the front in France in 1944. He was carrying with him a new and highly ingenious portable disc recording device which the BBC engineers had just developed. It was the latest thing and he demonstrated it to me with the greatest enthusiasm, tilting it alarmingly on one side as he talked into the microphone, bouncing it up and down as he recorded, and then playing it back triumphantly. He showed me the tiny motor, the miniature gears that kept the speed constant in every position, the way the recording head was cushioned against shock. He knew all about it and exactly how it worked. My own more primitive American instrument remained a complete mystery to me and I had to be accompanied by an expert to operate it. Richard handled his himself.

As we advanced into the increasing complications of television, Dimbleby remained abreast of the developing technology. He knew what every lens could do, the limitations of the image orthicon tube, the importance of lighting. Because of this, he knew what was likely to go wrong. This is an inestimable advantage to a broadcaster who stands there in his pool of light, with all the public responsibility for the programme on his shoulders, yet as isolated from the technical infrastructure which keeps him on the air as if he were in a diving bell. When something goes wrong, unless he knows what must have happened, he is lost, pitifully burbling and complaining in public view until it is put right. But Dimbleby could always guess what had happened and his rescues of broadcasts from technical difficulties became legendary. His famous aplomb was solidly based on professional understanding of the medium.

All this made him a joy to work with. Technical crews in America as well as in the BBC always liked to be assigned to a Dimbleby programme, and his obvious expertise was a great comfort to those who found themselves being interviewed by him on his programmes. A television interview can be a frightening experience, but Dimbleby was so obviously in command that his presence was very reassuring to the fellow in the other chair. He wasn’t particularly famous for it, but I always thought Dimbleby was a superb interviewer. His style of courteous persistence and the rapport he established with his guests often brought out a truer picture of his subjects than the more abrasive and challenging style of other interviewers which, by putting the subject on the defensive, tends to elicit only defensive reactions.

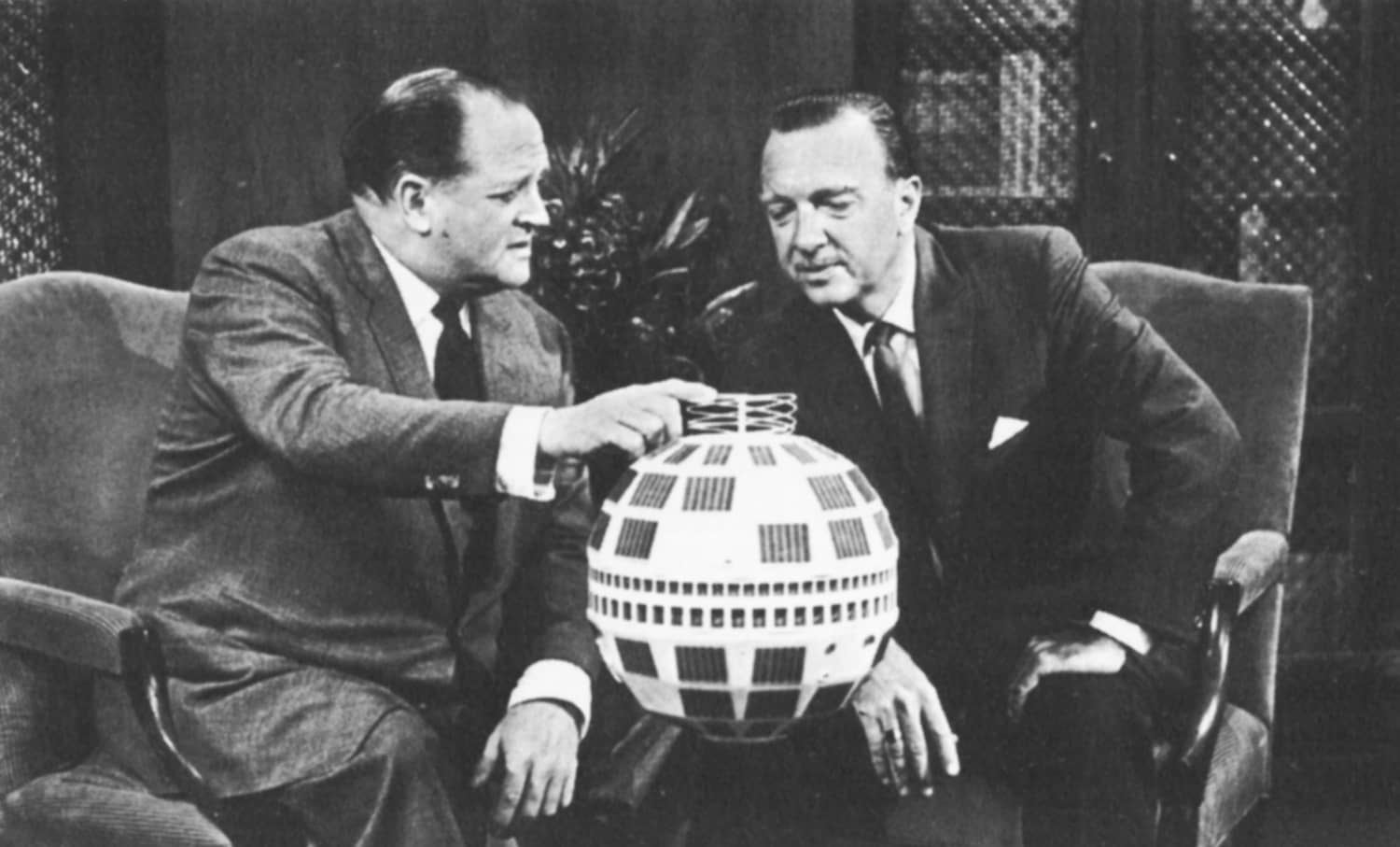

As it happened, we did a good many transatlantic broadcasts together when Telstar and Early Bird appeared in the heavens. He understood all about them, too. It was a great relief to know that he would be on the other end of these celestial communications, for if anything went wrong you could be sure that with Dimbleby there it would not be irretrievable. These broadcasts brought him more regularly before American audiences. He was the only British broadcaster who was immediately identifiable to large numbers of Americans. This is not surprising; Americans pride themselves on their ability to recognise the real thing.

Richard Dimbleby was the real thing, all right – both as a person and broadcaster. His influence upon the techniques of broadcasting was very great. Because he knew his job so well, he forced others to learn theirs. I’m sorry he won’t be around to see all the new developments in television. He would have been able to understand them completely and perhaps, thereby, make some of the rest of us understand them a little.