New York’s International Airport was its usual bustling self. As the lines of passengers shuffled past the shirtsleeved customs officers, one of the red-capped porters ambled across: ‘Aren’t you Mr Dimbleby?’

In London that question, usually preceded by a slow stare, would have been familiar enough. In Berlin, in Rome, even in Paris, it would not have been out of the ordinary. But this was New York – and when Richard Dimbleby arrived there one July evening in 1962, even Americans turned to stare.

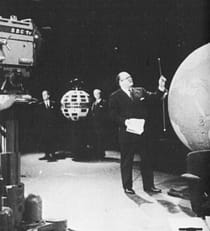

The reason for their new-found familiarity with the face known to all in Britain lay in a ball-shaped piece of metal hurtling through the sky: Telstar, the first communication satellite to provide a live television link between Europe and North America. The night before his arrival in New York, Richard had notched up another first: the first man to have televised live from Europe to America.

On 23 July 1962 Richard-spoke from Brussels on behalf of sixteen countries when he welcomed American audiences to their first live television view of Europe across 3,000 miles of Atlantic Ocean. Now he was back for the return half – and another first: the first Englishman to televise live from America to Britain. And to make him feel at home, the New York Times said of him on the morning of his arrival: ‘He dominates Britain’s television in a way that has no equivalent in the United States.’

That one historic broadcast from Europe – that cheerful ‘Hullo, New York’ from Brussels – made Richard Dimbleby’s friendly face and ample figure almost as familiar in the United States as in the United Kingdom. Within twenty-four hours of his arrival he had appeared on CBS with Walter Cronkite and also on NBC Television. New York’s press corps waited upon him. Variety – that bible of American show-business – spread his story across three columns. And as he stood on 53rd Street, in the shadow of Rockefeller Center, getting ready to televise live to London, many an American passer-by knew exactly who he was.

But they couldn’t have known that the first New York-based telecast was nearly swept off the screens. At the rehearsal, everything had gone smoothly. The cameras on the roof of the Rockefeller Center had pierced through the haze to give us perfect pictures of the towering Manhattan skyline. The camera in the Sixth Avenue drug store had just the right shot. A smooth and speedy commentary setting the scene was needed now; we only had ten minutes available; after that, we would lose the satellite. So there was a double nervous strain: the importance of the occasion with the twitching uncertainty whether the picture would successfully bounce off the moving satellite to England, and the urgent need to contain the programme within that limited span of time as soon as London signalled it was able to see New York.

With less than a minute to go, Richard’s monitor – the television set that would show him which picture was going out – collapsed. There he was, in mid-town Manhattan, the first Briton to televise live across the Atlantic, and he could not himself see any of the pictures that were being transmitted. Once again he was, for all practical purposes, blind. He could not see whether the pictures the American director was selecting were of the New York skyline or the cops or the drug store or the sidewalk. He had to guess and hope that the transmission would follow the rehearsal.

It did, fortunately. And after five hazardous minutes, the picture came back on Richard’s monitor. The trouble was over, though I doubt whether anyone at home ever noticed that something had gone very wrong, for Richard spoke as confidently as ever. But in those five minutes the American television crew learned and understood why he was the master of the craft of television reporting.