Ralph Murray, now the British Ambassador in Athens, was then in charge of the News Talks Section and was Dimbleby’s first mentor in the BBC.

Richard was, or seemed, a mere boy when he joined us in 1936. He was twenty-three. We were all pretty young, and he was five years younger than us all. We were blundering about among the problems and experiments of expanding the News Service. It had been a very modest affair of sub-edited agency news. Our ideas of expansion involved re-negotiation of contracts with the agencies to give us greater freedom of action, expansion of bulletins both in length and frequency, and the introduction into them of our own reports or illustrations or contributions on outstanding events both at home and abroad. Kenneth Adam’s restless spirit, untamed by two years on the Manchester Guardian, was stirring this pot; Tony Wigan had come from Belfast to apply his severe subediting standards; Angus Mackay from Edinburgh was licking the sports news into shape; Charles Gardner was a sub-editor then, too; others played their parts. I was in charge, on a shoe-string budget, of the beginnings of the reporting expansion, and to me Richard Dimbleby was assigned.

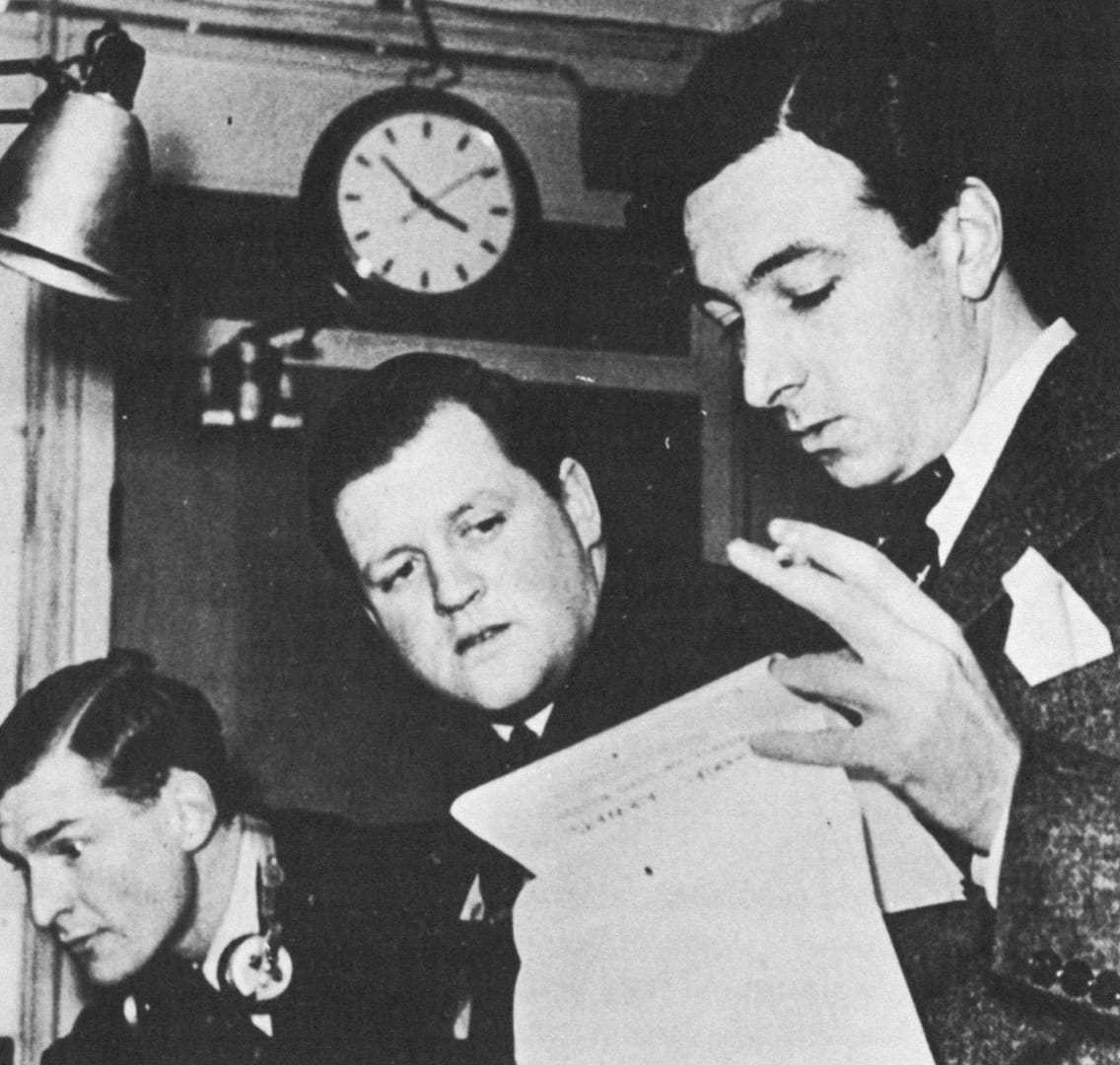

He was allotted of course the role of stooge, junior reporter, dogsbody, help. We were experimenting with our techniques, for which there was no precedent. We were not only young, we were mostly a graduate lot with some serious thoughts and criteria between us, most of us had more or less newspaper or news agency experience, a fair aggregate of intelligence and large areas of ignorance. We thought however we knew most of the answers. Richard was not only five years younger than the bulk of us – the exception was our dear, infuriating, experienced, scholarly, unreasonable and highly skilled old Scots news editor, the late R. T. Clark – he was not a graduate.

Richard brought to our team a tradition of newspaper ownership and management, which he had learned in his family newspapers, and a personal enthusiasm for reporting – but not the severe training of subediting. Mentally, he was the antithesis of all of us, whether of the slightly conceited, sceptical young graduates or of the disciplined, self-critical professional sub-editors. He was enthusiastic, uncritical, unintellectual. He not only knew none of the answers, he never even bothered about the questions. We nicknamed him, affectionately and artlessly, Bumble, because he was fat and buzzed: he was never either clumsy or pompous. But he had charm and immense self-confidence.

Now self-confidence in a journalist is vital. His profession constantly requires him to describe, judge, criticise or examine matters on which he necessarily cannot possibly possess much if any expertise, and in relation to which not only his judgment but even his description must rest on incomplete information. He must have the confidence, perhaps one should say the blind confidence, constantly to pronounce his judgment or publish his findings on this inadequate foundation, or he will break his heart and certainly will be a bad journalist. Plenty have it, and become in various degrees perspicacious, opinionated, analytical, waspish or portentous as their natures and professional opportunities allow. Perhaps fewer have it combined with charm; not merely charm of manner, but charm of nature such as Richard had.

The role of stooge did not suit him. Very quickly he was popping up with ideas, suggestions, contributions. Very soon he had worked his fat, quick, bouncing personality into a partnership in our team. But he was never arrogant, never impertinent, always loyal – though I think he muttered behind his hand at some of the Reithian restraints I imposed upon him. Quite soon he was constantly out on reporting assignments – not all of which were broadcast – and I began a private struggle with him over his use of language. He had then a positive enthusiasm for the cliché.

He seldom wrote what he was reporting, but rather recorded or transmitted it straight off his tongue: he had a rolling fluency in delivering it, but at a terrible stylistic price. I cursed him and slashed his copy and blue-pencilled his adjectives and cursed again and called upon him to think what language meant. In my pernickety sub-conscious mind I was demanding the astringency of a future John Freeman combined with the vocabulary of a James Morris. Richard went on rolling out his clichés with a relish and conviction that robbed them of their banality and positively gave them life. But, impervious to his real potentialities, I continued to try to shape him to impossible and inapplicable ideals.

Of course, the extreme condensation and economy of style required in contributions to those news bulletins were not his proper medium. I think he knew this at the time and was already working out how to transfer his resources of fluency to Outside Broadcast commentaries where they could find full scope: but he was feeling his way in the BBC and anyway was loyal to his team. Meanwhile he was most resourceful, as reporters must be, and reported all sorts of things. He sploshed about for days over-reporting some Fen floods. We went together on a rather stunty outing when a Dutch firm diverted a tin-dredger to have an unavailing go at the wreck of the Lutine off the Dutch island of Terschelling: Richard drove his car, which had cost him £3 and made awful clanking noises; we suffered a good deal of rough water and someone fell in; but in terms of news broadcasting the expedition was a failure.

He reported formal occasions with perhaps a whiff of his future carefully-judged style, aspects of the abdication crisis, of King George VI’s Coronation, occasionally sports events, accidents, anything that fitted in to our requirements – and then, as my work took me more and more abroad and the cloud of war became even in England bigger than a man’s hand, he reported military preparations, the end of the Spanish Civil War and Neville Chamberlain’s return from Munich; and I think at this stage his style tightened and he set himself the standards of thought and behaviour which underlay the sincerity in his war reporting and his carefully developed technique of extensive descriptive broadcasting and television commentary. I do not think my curses had helped much. If he was tolerable, acceptable or a delight to later millions of listeners and viewers, it was rather because his charm of nature gave him a modesty which not only communicated itself to his public but furnished a self-discipline far more effective than the astringent requirements of his News Service days.