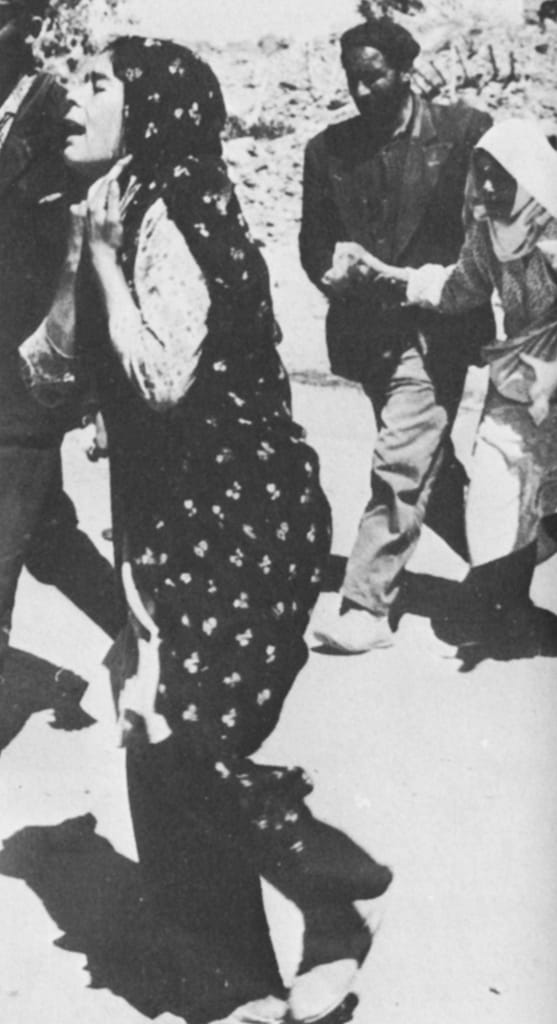

Richard Dimbleby always gave generously of his time and skill to broadcast appeals on behalf of causes near to his heart. Altogether he raised nearly £1 million. He was particularly concerned, and particularly effective, when the object of the appeal was relief of human suffering from some sudden emergency. One of these was the earthquake disaster in Western Persia in the late summer of 1962. Dimbleby appeared on the screen at the end of the news on Wednesday 5 September and showed pictures of the appalling damage done by the biggest natural disaster that had happened in any country for years. He said, ‘The need is enormous and the need is terribly urgent. It’s got to be something in the next forty-eight hours to be really effective. Not only for the drugs, the splints for shattered legs, for the blood plasma, for all the other necessities, but for something like this’ and at that point he held up what the Red Cross call a ‘Disaster Bag’ and showed that it had things like a toothbrush and towel, a handkerchief, a mug, a ball of string, pins, a spoon, a pencil and something else. ‘Because children, thank goodness, are the quickest people to disassociate themselves from the horrors around them, if they have got something to do, however simple it is, every one of these Disaster Bags has in it a ball – an ordinary ball that a child can play with and which will take its mind off things.’ He ended, ‘I believe that you will want to help. This is the quickest, best and most effective way to do it. I have never asked for anything more seriously than I am for this, at this moment.’

Dimbleby’s viewers did respond and respond quickly. £407,000 came in.

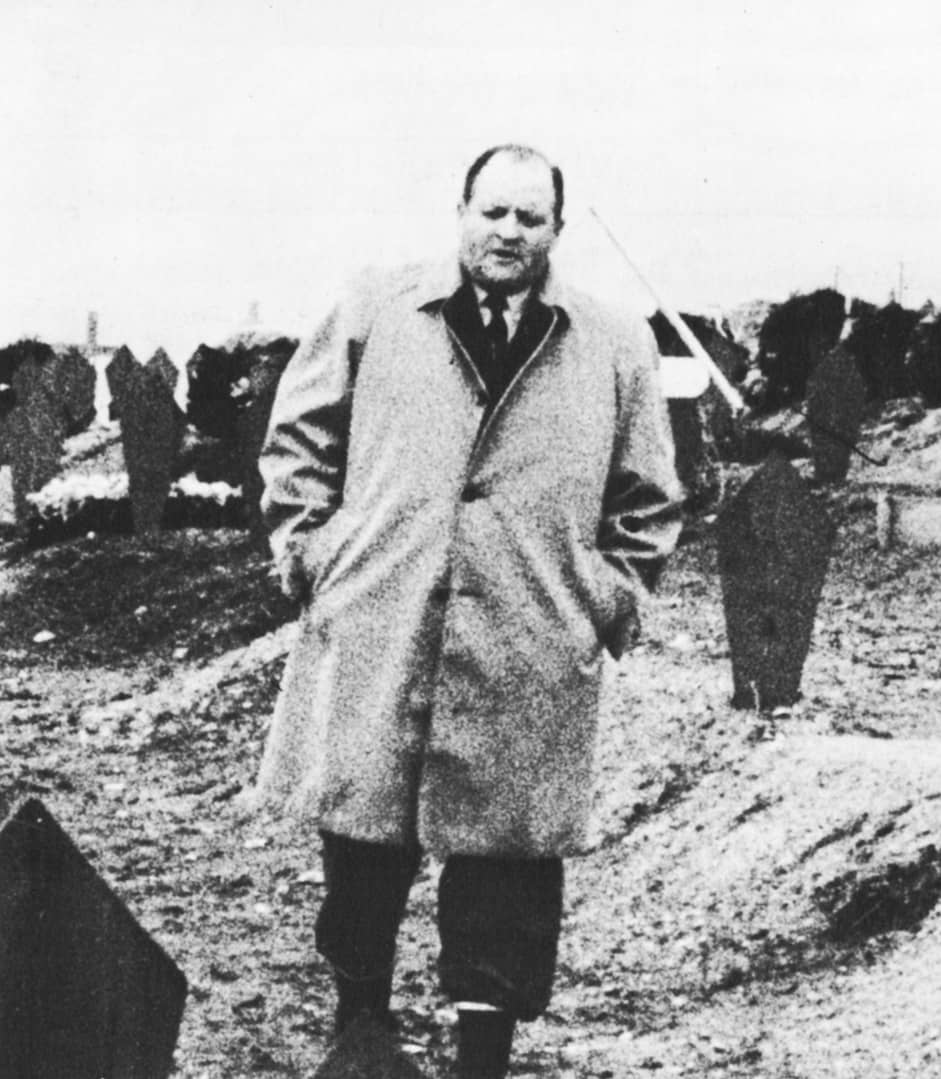

A year later there was again an appalling earthquake tragedy, this time at Skopje, the capital of Yugoslav Macedonia. Again Dimbleby was asked to make an emergency television appeal. He agreed to do so the same night, but then refused to go on the air until the Foreign Office were prepared to announce that in addition to the help the British Government was giving to Yugoslavia they would provide aircraft to deliver the goods that might be purchased out of private donations. Richard spoke movingly about the desperate need for shelter and the material for prefabricated houses. He said on 1 August 1963, ‘The Foreign Office have agreed to find the planes if we can find the money, and I am wondering if among the 10 million or so of you who are watching, we can find this amount of money now. The planes are due to leave on August 2nd or 3rd in time to assemble these buildings and provide shelter for these 100,000 homeless.’ He ended: ‘I do hope, as you did for the Persian earthquake last year, that you will respond in helping these desperately unhappy and stricken people.’