My first working meeting with Richard Dimbleby was in the Church of St Denis in Paris during the first Anglo-French TV Week in July 1952. I arrived on a Saturday afternoon to find Richard walking round, notebook in hand, contemplating the tombs of the Kings of France and soaking in the atmosphere of this ancient church full of memories of Joan of Arc. He had arrived the previous day, with all the textbook facts of the place completely mastered and neatly set out on his little cards. Now he was gaining what only the place itself could give so that he would come to his commentator’s task the following day clothed with a sense of place and occasion.

Then, as on many later occasions, I had a double job. I worked with Richard all through his preparations and sat beside him during his commentary in the role of expert adviser; and then, when Richard had finished his descriptive commentary and had set the scene, I took over the job as commentator for the religious ceremony itself. I don’t know which of these two jobs was the more daunting – to pick up the commentary from where the master himself had left off, or to attempt to satisfy his demand for meticulously accurate and detailed information about every aspect of the event which he was to describe.

In Rome it was: ‘Agnellus, who are the Busselanti? Why do they wear that curious crimson damask uniform? What are they in real life? How did they begin? How were these recruited?’ and so on, until every fact was mastered. I think we each of us could have described St Peter’s and the great Piazza outside, blindfold. He loved the enormous pillared colonnade of Bernini, ‘like two arms outstretched to embrace the world’, he said. And he came to know all the folklore of the place, and the little bits of gossip and delicious minor scandals as well.

He was too English ever quite to understand and accept the Italian way of ceremonial, with the Masters of Ceremonies giving frank and open direction as they led Pope and Cardinals through the maze of elaborate, ancient rites. ‘I wish that fellow would stop pushing the old man around’, he said, as Archbishop Dante tried to bring some discipline into Pope John’s slightly carefree ritual endeavours. On the other hand, he very much disliked any attempt to bring the old liturgy up to date. ‘The thing itself speaks,’ he said, when we were discussing the abandonment of Latin and the use of the vernacular, ‘you don’t need to understand every single word.’ And then he turned to me and said, ‘I’m not going to use your lovely Latin name any more. I am going to call you “Papa Lamb”’ – and Papa Lamb I was.

Others have written much about his industry and high professionalism. I remember we were in Rome for the Coronation of Pope John XXIII. Handouts and official papers were late in arriving through some misunderstanding. In the end, we had to go off with Charles Ricono of the BBC’s European Service to try to get hold of somebody important in St Peter’s late in the afternoon on the day before the event. We found Archbishop Dell’Acqua supervising the seating for Cardinals and diplomats in the Basilica. Charles explained our difficulty and persuaded the Archbishop to come into the Vatican and break open the little cupboard where the papers were kept. We got back to our hotel at 5 o’clock, and from then until after 11 I slowly made my way with Richard through every detail of his part of the ceremony. Coffee then, and off he went to his room to do some writing. And I had to begin to prepare my commentary from the beginning.

He was a master in the art of working with unknown producers from other television organisations whose style of cutting and mixing the cameras and whose whole method of production were strange to him. Often he would know only the opening and closing sequences: for the rest he had to follow the producer’s decisions. He would have no indication of the line of development or of the length of time that a picture might be held, and yet he went along easily and expertly, fitting himself perfectly into the situation and always tying his commentary into what was relevant on the screen.

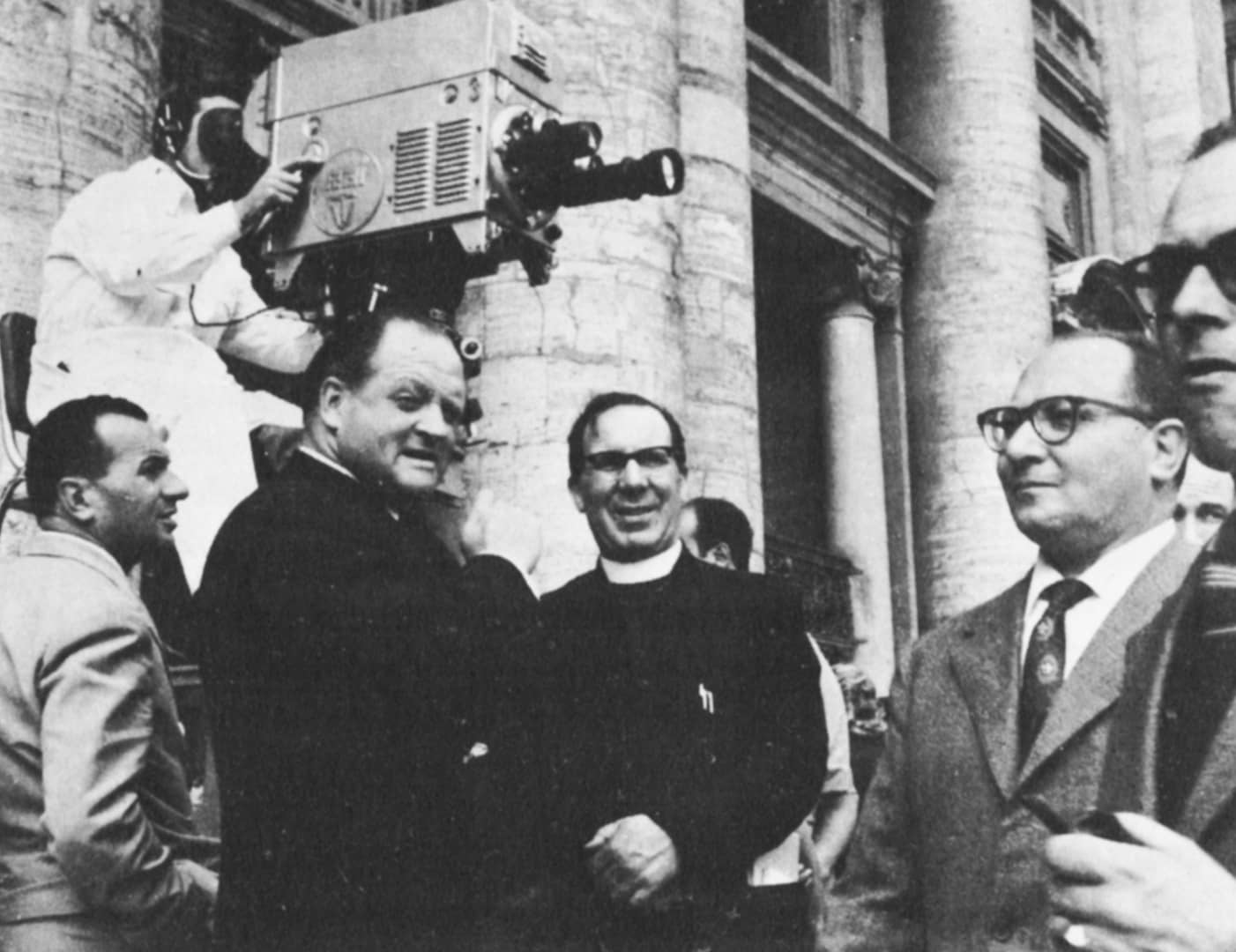

And he was unflappable. We were doing a twenty-minute contribution to Panorama in October 1962 from Rome on the occasion of the opening of the Vatican Council. The programme had to be fed along the Eurovision line to London at 3 o’clock for inclusion in that night’s programme and we were working like beavers in St Peter’s. Richard had just finished interviewing Cardinal Gilroy of Sydney when, without warning, all the lights suddenly went out. We had reached the lunch-time break and nothing that Paul Fox could say (and he was eloquent) could induce the Italian technicians to stay on the job. Richard was completely cool. In the end, he continued his work and the rest of the programme was televised using the house lights only.

My last evening with Richard was in Rome at the Coronation of the present Pope, Paul VI. It was a blazing June day in 1963. The ceremony was out of doors and Richard had had to spend a good deal of time out in the open with a handkerchief tied round his head, mastering the seating plans and other details of the ceremony. Afterwards, in the cool of the evening, we went off to have a little supper at a trattoria in the quiet piazza of S. Maria in Trastevere. We sat in the open, opposite the ancient church with its frescoes exquisitely lighted. It seemed a million miles away from the splendid scarlet and gold of the ceremony from which we had come. We sat there for nearly three hours and then, reluctantly, we got up and made our way back to the hotel, walking slowly through the ancient streets and past the cool fountains of Rome.