In June 1950 Richard Dimbleby received a letter from the company which laid the first telegraphic cable across the English Channel suggesting television might like to celebrate the forthcoming centenary of the event. He talked to Peter Dimmock, and a series of technical, municipal and diplomatic negotiations followed. At 9.30 p.m. on 27 August 1950 the television announcer at Alexandra Palace was able to say:

On 28 August 1850 the first telegram was sent from England to France by means of a cable laid across the Straits of Dover. Tonight – in a very few minutes – television pictures transmitted to Alexandra Palace from one of our mobile outside broadcast units at this moment in Calais will not only mark the centenary of that historic achievement of the last century, but herald in a new and important era in international communication.

Television had at last crossed the Channel. Richard Dimbleby was there to show viewers in Britain their first live sight of the floodlit Calais Town Hall. He was subsequently present on every major occasion when live British television opened its window wider still and wider on to the world outside. This time it was Calais en fête, followed three days later by a children’s programme from France. Soon it was to be a whole week of collaboration with the French Television Service:

The first time that we in the BBC worked with the new-found French Television Service in 1952, in a week of common programmes called ‘La Grande Semaine’, found Richard in his element. Not only was his French remarkably fluent, but he loved France and had a great sympathy for the French way of life. I remember particularly one of these early programmes, a relay from the Louvre with Richard as the British commentator and myself as co-producer, with a very talented French director whose experience and reputation in the film world was considerable, but whose knowledge of the mechanics of television was necessarily limited. Since a British outside broadcast unit was handling the broadcast, I asked René to show us what he would like covered in the Louvre and in particular what areas required special lighting.

As the three of us walked from salle to salle, and René’s list of priorities grew larger and larger, it became obvious that he was blissfully ignorant of the technical restrictions of an outside broadcast unit. When finally we reached salle number fourteen, I felt obliged to tell René that in terms of continuous live television there was not enough light generated in Paris, nor enough camera cable manufactured in my country, to cover all that he wished to show to British viewers in the Louvre. ‘Courage, mon brave,’ cried René and swept us on to the next room. Richard thought it all a splendid Gallic joke and, as he said, “That’ll teach you to be a pedestrian British O.B. producer’. And, of course, he was right. While we in the BBC started that week vaguely contemptuous of the technical ignorance of our French colleagues, I for one finished with a very healthy respect for their imaginative approach to television.

The only time I ever saw Richard lose his temper was in a later programme in that same visit. This was a relay from the Bateau Mouche, one of the river boats on the Seine, and was intended to be a study in French elegance, taste and talent, involving a mannequin show interspersed with top French artists like Jean Sablon, the whole set against the fabulous backdrop of the Paris skyline on a warm July night. It should have been a winner, but for a number of reasons, mainly technical, but in part ones of temperament, this broadcast turned out to be a disaster on such an imperial scale that a long-suffering Cecil McGivern, then the BBC’s Controller of Programmes, ordered the programme to be faded halfway through the transmission. All this time Richard as compère had been keeping a brave face as chaos developed backstage. When the cease fire finally went and McGivern withdrew his troops, Richard walked down the gangplank white with anger, throwing, if I remember rightly, a couple of bottles of champagne and a chair into the Seine, saying in a cold hard voice ‘I’ll never work with these clots again’. Whereupon the unhappy French technicians, who had been primarily responsible for the breakdown, looked up at Richard with admiration, recognising in their terms a man of spirit and élan who for ever afterwards had a special position in the affections of the French Television Service.

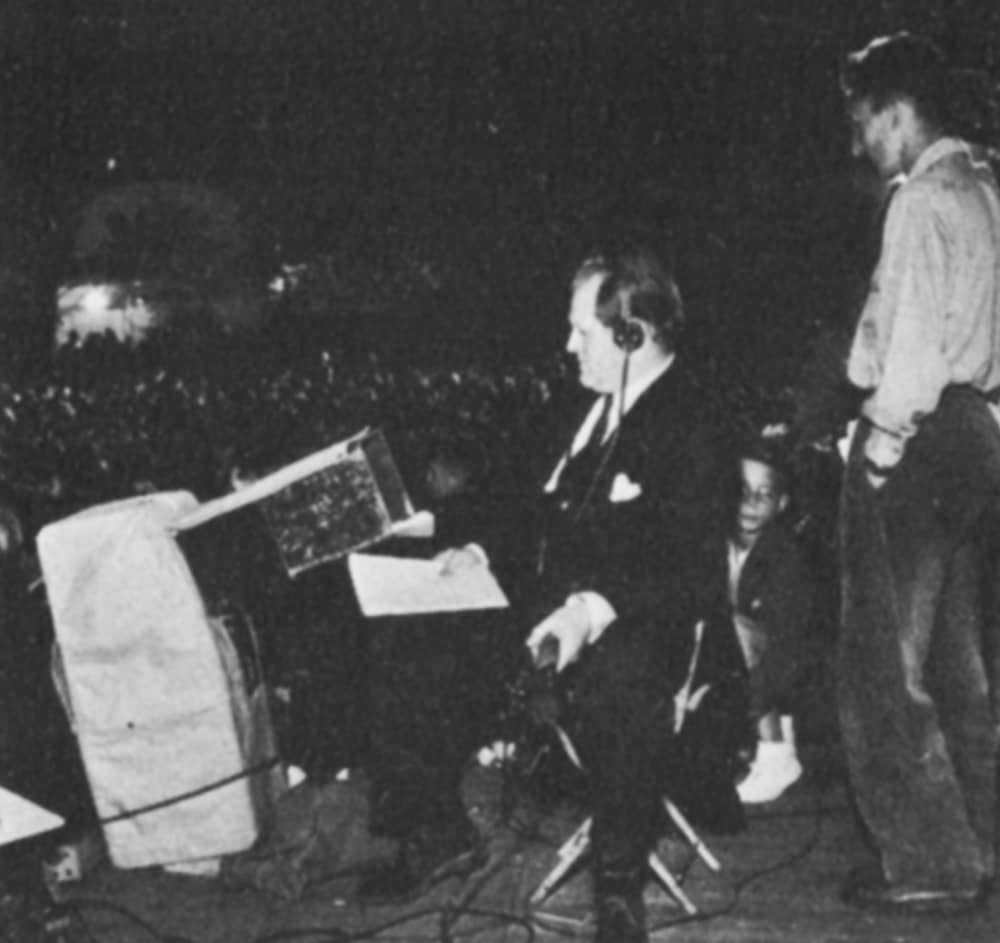

In those most difficult of programmes, involving co-operation between two headstrong and highly nationalistic television services, speaking two separate languages, it was always Richard who best survived the heat of the day. When we’d finished, usually very late at night, we would pile into the back of the big open Jaguar he had at that time and in the heady warmth of a July night he would drive down the Champs Elysées with all the verve and skill of a French taxi driver, on our way to what quite often was our first proper meal of the day. But whatever time we might get back to our hotel, Richard never ever made the mistake of leaving undone his homework for the following day. At one or two in the morning we’d be back in his room, checking the details of the next broadcast, as he wrote, in that large rather flowery hand, his notes on cards which he carried with him and used in his commentaries all over the world.