Mrs Wyndham Goldie was my redoubtable deputy throughout the period I was in charge of the talks and current affairs programmes on BBC Television. I asked her to take a special responsibility for the General Election Results programmes, for the transmogrification of Panorama, and for launching the first programmes giving consumer advice on named products, all enterprises in which she collaborated closely with Richard Dimbleby. She recalled his courage in an article written for the ‘Sunday Telegraph’:

Richard Dimbleby never questioned the authority of even the youngest producer. He never quibbled about details of content and would happily accept linking words written for him and make only minor changes. Yet he would never accept a programme which cut across the grain of his personality.

It’s the existence of this grain, of this quality inherent in their very being, which makes the great television professionals. It wasn’t simply because Ed Murrow was so brilliantly a professional that he dominated the best of American television for so long. Nor was Dimbleby’s continuing and almost embarrassing success – so that people asked ‘Why must it always be Dimbleby?’ – due to his professionalism alone.

There are plenty of television professionals. Some of them seem to have chromium plate in their veins. Not Richard. He existed as a man. He wanted to be a surgeon. And when I got to know him I realised that he combined, with his meticulous attention to detail, a human compassion and yet a professional detachment which made me understand why he regretted that he had to go into the family newspaper business; why so many of his friends were surgeons, and why he had a continuing interest in surgery.

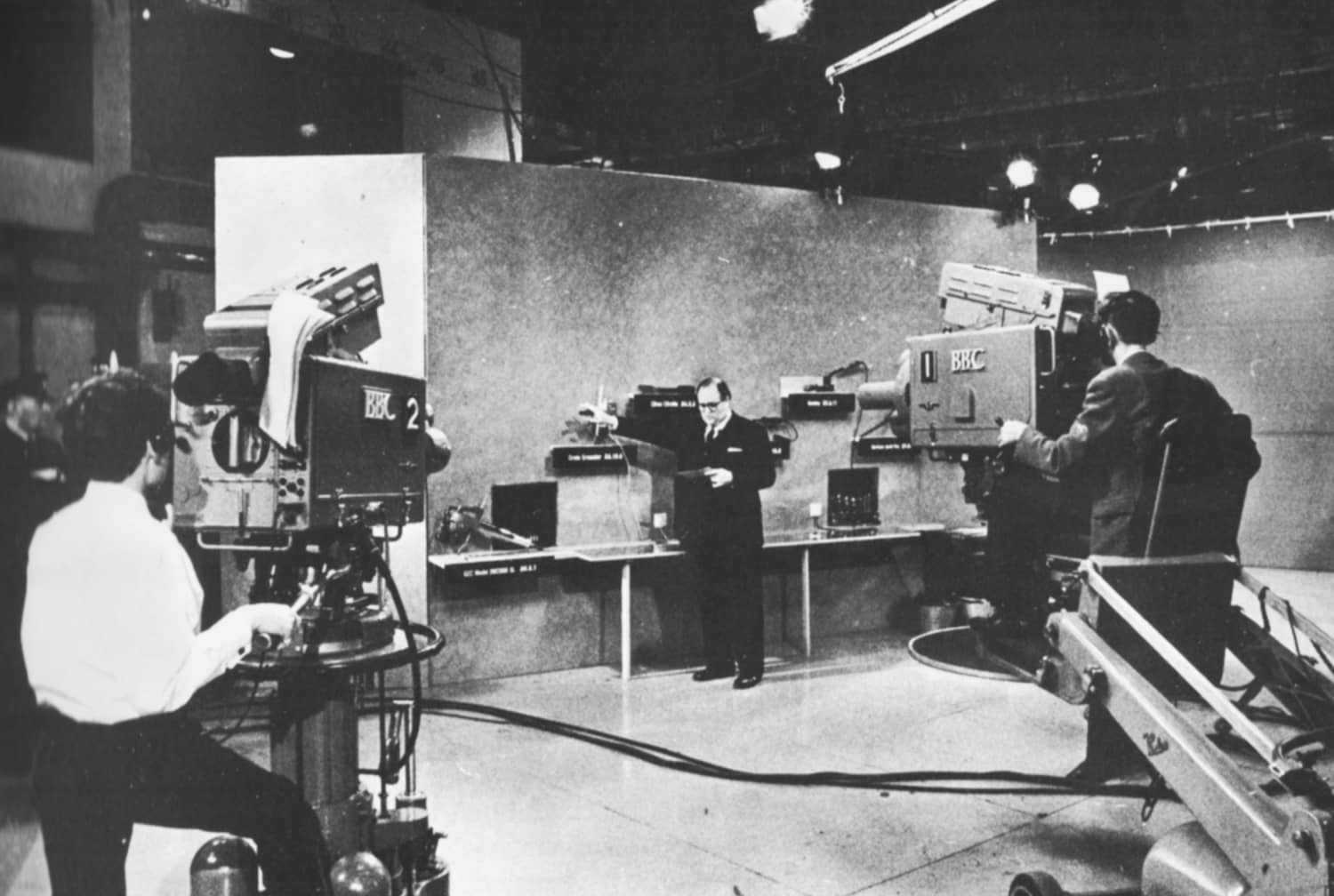

All this, and his personal courage, was brought home to me one night early in 1962 when I was making a pilot for a programme called Choice which, for the first time in television, gave advice to consumers, naming manufacturers and prices.

The Federation of British Industries was alarmed. They warned me that there was a serious danger of lawsuits involving sums of money. In the early days eight lawyers had to vet each script and each videotape before transmission. I believed that the only person who could undertake this difficult job was Richard, and he accepted when he was convinced that it was a public service.

But we had to make a pilot programme to persuade the Board of Governors that Choice was a starter. The dates for recording the pilot were fixed. Richard said: ‘I’m sorry, but they’re absolutely impossible and so I can’t do the thing at all. Obviously whoever does the later programmes must do the pilot.’

Now I knew then, what we all now know, that Richard was undergoing treatment for cancer and he told me that the reason why he couldn’t manage this particular day was that it was one on which the hospital had arranged for him to have treatment. I said that we would make any arrangement to suit him and he eventually agreed that if he walked through the programme in the early afternoon, went oft at four, and came back at six for a final rehearsal and recording, all would be well. He was always punctual. So I was astonished when 6.30, 7, 7.15 came and there was no sign of Richard.

I was told that it would now be impossible to complete the rehearsal and then record. Just after 7.15 Richard arrived, said ‘I’m terribly sorry’, and hurried up to the studio. We rehearsed in part, then he recorded brilliantly a half-rehearsed programme. When I went downstairs I found him eating and drinking and amusing the rest of the participants by some of the good-humoured stories he told so well. Then he took me aside and said: ‘I’m so sorry if I messed up the pilot, they didn’t warn me that I was going to be under a total anaesthetic for two hours and I’d no idea what was happening.’

That he should have carried on with this difficult rehearsal and recording was astonishing. That he should under these circumstances apologise for being late was incredible. But that was Richard. It was impossible not to admire him as well as to like him. It was equally impossible to imagine him ever being petty or mean or ungenerous. And this came over the television screen and gave authority not only to his own performance but to the programmes in which he appeared.